Does it matter if it's real? Clifford's Ethics of Belief

Be sure you understand

- How Clifford thinks about personal belief

- Clifford's attitude toward the shipowner in the story he begins with

- How his strong opinions about the importance of basing beliefs on evidence is a moral position

- The dangers associated with credulity and viral misinformation

Reading

W.K. Clifford, "The Ethics of Belief" (included, with interpretation, in the lesson below)

Everyone should feel free to believe whatever they want to.

This is one of the foundational ideas of Western Liberal Democracy. Everyone should have freedom of thought, freedom of speech, and freedom of faith. What people believe is their own business, and no one should try to tell them otherwise. I would imagine that most of you agree with this view.

This week we are going to look at the ideas of someone who strongly disagrees with it.

Living in the Matrix

Many ideas from last week's reading, the Allegory of the Cave, are powerfully echoed in a 1999 science fiction classic, The Matrix.

In The Matrix, the character Neo is a computer hacker who starts to notice weirdness in his day-to-day life and is vaguely uncomfortable with his sense of reality. He is approached by the character Morpheus, who tells him that reality is not what he thinks and offers him the chance to find out what is really going on:

Neo has the choice: he can take the red pill and wake up and see reality as it actually is — however painful that may be. Or he can take the blue pill and remain in the delusional state in which most people live. Would you have the guts to wake up? Would you want to?

The question is often seen as an updated version of the situation of the prisoners in Plato’s cave. Plato, of course, would say that you should definitely take the red pill and wake up, because the truth is the highest value and the only way to acheive "The Good." Even if it's hard and you don't like it. As Socrates supposedly said before drinking poison, "The unexamined life is not worth living." But I'm sure not everybody would agree with Socrates.

Without spoiling the whole movie for you, I can tell you that our hero does take the red pill. The pill breaks the hold the Matrix has on his mind. He wakes up and finds that he is actually vegetating in a pod, hallucinating the world he thinks we live in. The world we think is real is a virtual simulation, a mass hallucination being generated by the machines that actually run the world now. This mass hallucination is called The Matrix. In fact, earth has been devasted in a war between the humans and the machines. The humans lost and are held captive. They are used as a kind of living "batteries" (don't expect this to make sense - it's an allegory, like Plato's cave). We think we are living lives in the real world, but actually we are just generating energy for the machines, who in turn provide us with a simulated experience of the life before the war.

As horrible as the true reality is, Neo is glad to be able to know what is really going on, and he joins Morpheus and his rebels who are fighting the machines and trying to break the spell the Matrix has put on most of humanity.

But some people would prefer to remain with the shadows they are comfortable with, even though they know they are shadows. And this is dramatized later in the film. One of the rebels, Reagan, is tired of fighting and just wants to enjoy his life. He decides to make a deal with the machines (who appear in the movie as mirror-shade wearing men-in-black types):

Reagan has decided he doesn't care what is real or true or good. He just wants to have a pleasant life (simulated) and to forget that he has betrayed his fellow humans in their fight to free themselves from the machines.

The Ethics of Belief

Everyone should feel free to believe whatever they want to.

To repeat, freedom of belief is one of the foundational ideas of a Western Liberal Democracy, such as we have in Canada.

We are now going to look at the ideas of someone who strongly disagreed with the idea that people should allow themselves to believe whatever they want. But he was not a totalitarian or a religious fanatic. His argument against this kind of "right to believe whatever you like" is actually a moral argument.

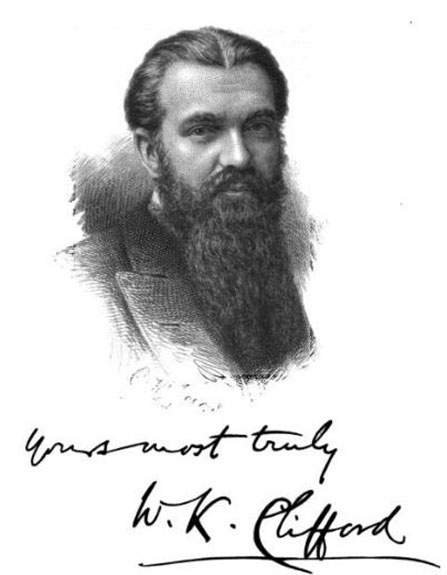

William Clifford was a British philosopher who lived in

the 1800s. He was worried that humanity would allow itself to become credulous — too quick to believe whatever we hear or whatever we like the sound of. He was also concerned that people may put far too much emphasis on whether or not someone is sincere when they tell the rest of

us what they believe, as if all manner of foolish and misguided behaviour should be allowed as long as it

comes from a sincere belief. Above all, he worried that we would mistake the claim “I have a right to my opinion” for the claim that “all opinions are equally right.” To help fight against these various threats, Clifford wrote “The Ethics of Belief,” a passionate argument in support of the claim that “it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.”

When Clifford said that it is "wrong," he didn't just mean that it is incorrect, dangerous for the believer, or unscientific; he meant it is morally wrong

Let's go through his argument paragraph by paragraph. This is the assigned reading in full, so if you read it with me here you don't have to read it seperately as well, though the more times you read something, the better and more deeply you will understand it! If you like, you can go read it all by yourself first and see what you make of it. You can also read it again later, after we have gone through it in this lesson.

Clifford's writing from 150 years ago will now seem a bit "old timey" and it may be hard to understand some of what he says, so I will paraphrase and discuss as we go along.

Like Plato, Clifford uses a story to get his readers dramatically involved in the topic he wants to discuss:

A ship owner was about to send to sea an emigrant-ship. He knew that she was old, and not over-well built at the first; that she had seen many seas and climes, and often had needed repairs. Doubts had been suggested to him that possibly she was not seaworthy. These doubts preyed upon his mind, and made him unhappy; he thought that perhaps he ought to have her thoroughly overhauled and refitted, even though this should put him to great expense. Before the ship sailed, however, he succeeded in overcoming these melancholy reflections. He said to himself that she had gone safely through so many voyages and weathered so many storms that it was idle to suppose she would not come safely home from this trip also. He would put his trust in Providence, which could hardly fail to protect all these unhappy families that were leaving their fatherland to seek for better times elsewhere. He would dismiss from his mind all ungenerous suspicions about the honesty of builders and contractors. In such ways he acquired a sincere and comfortable conviction that his vessel was safe and seaworthy; he watched her departure with a light heart, and benevolent wishes for the success of the exiles in their strange new home that was to be; and he got his insurance money when she went down in mid-ocean and told no tales.

So the owner convinces himself that his ship is seaworthy, and he tells himself that "providence" (God, fate, some higher power) can be relied on to look after the immigrants travelling on his ship. It may not be clear to our cynical modern ears, but Clifford expects you to be disgusted by the shipowner's conclusion, when the owner gets the insurance money. Not to think what a clever shipowner; he collected twice, once from the immigrants and once from the insurance company; now he can buy a new ship, or retire in style! Clifford considers the man to be monstrously immoral, and wants us to think badly of him. This is clear from the next thing he writes:

What shall we say of him? Surely this, that he was verily guilty of the death of those men.

"Verily" is an old-timey, Bible-sounding word. It means "truly." Clifford claims without hesitation that the shipowner was responsible for the deaths of the immigrants.

It is admitted that he did sincerely believe in the soundness of his ship; but the sincerity of his conviction can in no wise help him, because he had no right to believe on such evidence as was before him. He had acquired his belief not by honestly earning it in patient investigation, but by stifling his doubts. And although in the end he may have felt so sure about it that he could not think otherwise, yet inasmuch as he had knowingly and willingly worked himself into that frame of mind, he must be held responsible for it.

We might paraphrase this in less antique language: It’s true that the shipowner did sincerely believe his ship was safe. But how sincere his faith was is no excuse. Because he had no right to believe based on the evidence he had. His belief had not been earned through careful investigation, but simply by stifling his doubts. He may have convinced himself to the point where he couldn’t think otherwise, but because he had knowingly and willingly talked himself into it, he must be held responsible.

Let us alter the case a little, and suppose that the ship was not unsound after all; that she made her voyage safely, and many others after it. Will that diminish the guilt of her owner? Not one jot. When an action is once done, it is right or wrong forever; no accidental failure of its good or evil fruits can possibly alter that. The man would not have been innocent, he would only have been not found out. The question of right or wrong has to do with the origin of his belief, not the matter of it; not what it was, but how he got it; not whether it turned out to be true or false, but whether he had a right to believe on such evidence as was before him.

Many of us would probably agree that the shipowner was indirectly responsible for the deaths, but now Clifford makes a more radical claim. He asks us to imagine that the ship was in good enough shape to make the voyage safely this time, in spite of evidence that it might not be. Now is the ship owner guilty of anything? No one died or suffered. For Clifford, he has still done something irresponsible, bad, "sinful" - he just got away with it this time.

Clifford says No, the shipowner is still guilty.

It is not only a question of what the outcome was, for Clifford, but of whether the owner had a moral right to make the decision he made based on the way he had arrived at his beliefs. He was wrong, even if nothing bad came of it this time.

[I]t is not possible so to sever the belief from the action it suggests as to condemn the one without condemning the other. No man holding a strong belief on one side of a question, or even wishing to hold a belief on one side, can investigate it with such fairness and completeness as if he were really in doubt and unbiased; so that the existence of a belief not founded on fair inquiry unfits a man for the performance of this necessary duty.

In this paragraph, Clifford makes a couple of observations: You can’t separate the belief from the action it leads to and then condemn the action without condemning the belief. So the owner shouldn't have sent his ship out, because he did so based on an unsubstantiated belief. His ship could indeed have been unseaworthy, even if it wasn't.

Clifford acknowledges that it is hard to be impartial: Nobody with a strong belief on one side of a question, or even wanting to have a strong belief, is really capable of investigating it as fairly and fully as if he really weren’t sure. If he already has a belief not founded on impartial investigation, he’s not going to be able to perform an impartial investigation. Clifford recognizes that it is hard for a person to be impartial. But rather than saying that's alright then! and letting us off, he clearly wants us to work against this natural difficulty we have with keeping an open mind and looking into things carefully.

Nor is that truly a belief at all which has not some influence upon the actions of him who holds it. … No real belief, however trifling and fragmentary it may seem, is ever truly insignificant; it prepares us to receive more of its like, confirms those which resembled it before, and weakens others.

And there is no belief that doesn't have an influence on a person's actions. Our actions, for Clifford, are always a result of our beliefs - all of them. Any wrong belief we have, Clifford thinks, encourages us to accept more wrong beliefs, helps confirm other wrong beliefs we may already hold, etc.

In the… [case which has] been considered, it has been judged wrong to believe on insufficient evidence, or to nourish belief by suppressing doubts and avoiding investigation. The reason of this judgment is not far to seek: it is that in both these cases the belief held by one man was of great importance to other men. But forasmuch as no belief held by one man, however seemingly trivial the belief, and however obscure the believer, is ever actually insignificant or without its effect on the fate of mankind, we have no choice but to extend our judgment to all cases of belief whatever.

In the shipowner example, the reason believing without investigation was wrong is pretty obvious: the belief held by one person ended up having a terrible impact on the lives of other people. But Clifford considers no belief – no matter how insignificant the belief seems to be or how insignificant the believer – ever to be completely insignificant, or without an effect on the fate of humanity. So he proposes that the judgment can be applied to all cases of belief.

No simplicity of mind, no obscurity of station, can escape the universal duty of questioning all that we believe. It is true that this duty is a hard one, and the doubt which comes out of it is often a very bitter thing. It leaves us bare and powerless where we thought that we were safe and strong. To know all about anything is to know how to deal with it under all circumstances. We feel much happier and more secure when we think we know precisely what to do, no matter what happens, than when we have lost our way and do not know where to turn. And if we have supposed ourselves to know all about anything, and to be capable of doing what is fit in regard to it, we naturally do not like to find that we are really ignorant and powerless, that we have to begin again at the beginning, and try to learn what the thing is and how it is to be dealt with—if indeed anything can be learnt about it. It is the sense of power attached to a sense of knowledge that makes men desirous of believing, and afraid of doubting.

This paragraph begins with a quaint way of speaking that will probably not be clear to most modern readers: "No simplicity of mind, no obscurity of station, can escape the universal duty of questioning all that we believe." What he is saying here is this: It doesn’t matter how "slow" or unreflective you are; it doesn’t matter how unimportant a person you are - you can’t escape the responsibility you have of questioning everything you believe. He is anticipating objections from ordinary people, who will say "I'm not important; I'm not very bright. What I believe doesn't matter to the rest of humanity." Clifford disagrees violently with that attitude. As he sees it, every one of us has beliefs which together are shaping the fate and future of other people and of all humanity, and we can't excuse ourselves just because it seems like more important people don't care what we think, or we ourselves think that our beliefs aren't of any significance to the rest of the world. Everyone's beliefs, as Clifford sees it, have an impact in the world.

He goes on to acknowledge how hard this is - what a terrible responsibility we all have if what he says its true, and how recognizing that our beliefs need more questioning makes us feel weak, so we avoid it for that reason. To paraphrase: Feeling doubt is often a very unpleasant thing. The uncertainty, the anxiety, makes us feel naked and powerless where we thought we were safe and strong. To know all the answers makes us feel like we can handle any situation. We feel much happier and more secure when we think we know what to do, than when we don’t know the answers and don’t know where to look for them. And if we have supposed we knew all we needed to know about something, and that we knew how to do what is appropriate about it, we naturally don’t like finding out we are really ignorant and powerless, and that we need to start all over and try to understand the situation and how we should deal with it – if we even can. (Here I'm getting echoes of Plato, but maybe it's because I've paraphrased them both ; -)

Clifford thinks that it is the sense of powerlessness we feel when we are in doubt that makes us avoid doubt any way we can. We are afraid to doubt. But for Clifford, doubting is our moral responsibility, because the fates not just of ourselves but of other people depend on what we believe and our having validated those beliefs.

This sense of power is the highest and best of pleasures when the belief on which it is founded is a true belief, and has been fairly earned by investigation. For then we may justly feel that it is common property, and hold good for others as well as for ourselves.

Then we may be glad, not that I have learned secrets by which I am safer and stronger, but that we men have got mastery over more of the world; and we shall be strong, not for ourselves, but in the name of Man and in his strength. But if the belief has been accepted on insufficient evidence, the pleasure is a stolen one. Not only does it deceive ourselves by giving us a sense of power which we do not really possess, but it is sinful, because it is stolen in defiance of our duty to mankind. That duty is to guard ourselves from such beliefs as from a pestilence, which may shortly master our own body and then spread to the rest of the town.

The power we feel in belief is the best when we know we have a well-founded belief. Then it's not just our belief, but something that holds true for all of humanity. Clifford considers a belief that is unfounded to be actually sinful. We are sinning not against God, but against our fellow human beings. We should all be working together for a shared belief based on evidence and reality. Otherwise, some people will wrongly suffer because of irresponsible beliefs held by others.

For Clifford, unfounded beliefs, are like a communicable disease that we need to be careful not to be infected by and not to infect others with. The image is powerful in the 21st century, not only in the world of COVID-19, but in the world of "viral" misinformation that the Internet makes possible. As humanity comes together and communicates more and more, Clifford would probably argue, the moral necessity of sharing beliefs that are well-founded becomes more obvious. People's rights, livelihood, and lives can depend on what beliefs other people are exposed to and perhaps take on without investigating them.

And, as in other such cases, it is not the risk only which has to be considered; for a bad action is always bad at the time when it is done, no matter what happens afterwards. Every time we let ourselves believe for unworthy reasons, we weaken our powers of self control, of doubting, of judicially and fairly weighing evidence.

….

[I]f I let myself believe anything on insufficient evidence, there may be no great harm done by the mere belief; it may be true after all, or I may never have occasion to exhibit it in outward acts. But I cannot help doing this great wrong towards Man, that I make myself credulous. The danger to society is not merely that it should believe wrong things, though that is great enough; but that it should become credulous, and lose the habit of testing things and inquiring into them; for then it must sink back into savagery.

Here Clifford makes an additional argument: every time we allow ourselves unfounded beliefs, we are conditioning our minds to think that's okay, to be ready to take on more unfounded beliefs. The danger, as he sees it, is not just that a person may believe one wrong thing - which may or may not have an impact in the real world - but that we become credulous. Credulous means eager to believe, too ready to believe without proper consideration and investigation. The easier and more accepted this becomes, the more we slip backward toward primitive ways of existing, as Clifford sees it. Civilization depends on people who hold responsible beliefs.

Now Clifford restates simply and powerfully what he believes, and wants us to accept:

To sum up: it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence.

This is an unusually bold statement, shocking in our world of relativism and tolerance of others' opinions and belief-systems. Most of us today have come to think, just as Clifford feared, that people should not hold each other responsible for their beliefs and that there is room for lots of different opinions, attitudes, and beliefs. Though Clifford never mentions religion, presumably he doesn't think that people should believe in religions that can't be investigated and substantiated with evidence. Clearly some of the beliefs found in some religions - for instance, that women should be subordinate to men - might be thought to have a negative real-world impact on some people.*

But at the same time, Clifford's own view is sort of "religious" itself. It starts from the faith that we have a responsibility to other people, and that humanity is in this together and needs to hold itself accountable. Clifford's repeated use of the word sin shows that he is coming from a strong moral starting assumption:

If a man, holding a belief which he was taught in childhood or persuaded of afterwards, keeps down and pushes away any doubts which arise about it in his mind, purposely avoids the reading of books and the company of men that call into question or discuss it, and regards as impious those questions which cannot easily be asked without disturbing it —the life of that man is one long sin against mankind.

A person who holds onto a doctrine they were brought up with or became attached to later and who stifles their doubts or rationalizes away objections, for Clifford, is a bad person. They are "sinning" against their fellow human beings.

Inquiry into the evidence of a doctrine is not to be made once for all, and then taken as finally settled. It is never lawful to stifle a doubt; for either it can be honestly answered by means of the inquiry already made, or else it proves that the inquiry was not complete.

For Clifford, our moral duty is to question our beliefs, continually. Doubts are to be welcomed and investigated, not stifled. Stifling one's doubts is evil.

"But," says one, "I am a busy man; I have no time for the long course of study which would be necessary to make me in any degree a competent judge of certain questions, or even able to understand the nature of the arguments."

Then he should have no time to believe.

Clifford ends by imagining someone has been listening to what he has been saying and now replies: "Well, I don't have time to look into all my beliefs. I'm a busy man."

This always reminds me of something I once read, where a more famous figure said he didn't have time to read anything long or complicated. See if this sounds like you:

He has no time to read, he said: “I never have. I’m always busy doing a lot. Now I’m more busy, I guess, than ever before.”

He does not need to read extensively because he reaches the right decisions “with very little knowledge other than the knowledge I [already] had, plus the words ‘common sense,’ because I have a lot of common sense and I have a lot of business ability.”

He said reading long documents is a waste of time because he absorbs the gist of an issue very quickly. “I’m a very efficient guy,” he said. “Now, I could also do it verbally, which is fine. I’d always rather have — I want it short. There’s no reason to do hundreds of pages because I know exactly what it is.”

As he has prepared to be named the Republican nominee for president, Donald Trump has not read any biographies of presidents. He said he would like to someday.

Yes, those are the attitudes of the former president, quoted in a profile in The Washington Post before he was elected (July 17, 2016). Clearly, many Americans are in sympathy with the way Trump thought and felt.

Clifford, I imagine, would have been morally appalled by the ex-president's unwillingness to investigate, doubt himself, do research, learn, and change his mind. For those who think like Trump, the force of one's convictions and the sincerity of one's beliefs are what are important. Clifford says no. Power is not an argument. Forcefulness of belief in yourself is not an argument. Everyone needs to take the time to look into things deeply and find out whether their belief is justified. If they don't have time to do that, they shouldn't believe.

I'm sure we have all heard ourselves saying things we didn't look into personally and having opinions we have no right to have. My friend Lewis has a new opinion about the coronavirus every time I see him, usually based on something he read or heard somebody say on the news plus what he wants to believe, or thinks will sound clever or interesting. I do this too at times, of course. Most of us do. Clifford considers this kind of attachment to interesting or dramatic or partial information that we have not actually looked into to be a kind of viral infection of our fellow humans, as hearsay, fantasy, and misinformation (or disinformation) are spread throughout a population eager to believe without doing the work they should do to have valid beliefs.

In GNED 101, we often discuss various contemporary moral or political disagreements to illustrate Clifford's ideas, for instance anti-vaxxers vs those who believe in vaccination. At the moment we have an example that is very much with us, so you might want to think about it. Some people believe that wearing masks has little to no benefit for slowing the spread of COVID-19. Others believe that regardless of the science, they shouldn't have their rights infringed by being forced to wear masks if they don't want to. What do you think Clifford would say to these people about their beliefs?

The tradition of liberal democracy on which Canada and the United States are founded holds the freedom of an individual to be one of the highest goods and what the government is there to protect. This includes freedom of belief, of course. We'll take a closer look at liberal ideals in the lesson on politics later, but the average person tends to interpret this along the lines of the sentence I started with:

Everyone has a right to believe whatever they want to.

Clifford's point of view is strongly opposed to that proposition: "it is wrong always, everywhere, and for anyone, to believe anything upon insufficient evidence." But his attitude is not a political position but rather a moral appeal to his fellow human beings. Clifford doesn't think the government should make everyone believe a particular thing (assuming it could somehow do that), but rather he is urging his fellow human beings to make the decision to believe only with evidence for themselves. He is expressing his morality, not his politics. Maybe you could even say that he is proclaiming his own humanist "religion," a belief that we humans make the world - each and every one of us - and that we owe it to each other to question our beliefs, and if necessary to replace them with better ones. Our culture generally proclaims the universal value of individual freedom; Clifford proclaims the universal value of interpersonal responsibility.

FOR TESTING

- How Clifford thinks about personal belief

- Clifford's attitude toward the shipowner in the story he begins with

- How his strong opinions about the importance of basing beliefs on evidence is a moral position

- The dangers associated with credulity and viral misinformation

* - The excerpt from Clifford we are reading is part of a philosophical debate between Clifford and the American philosopher William James. James is famous for coining the phrase "leap of faith" to describe situations in which we don't have time to look for evidence and where hesitation might be worse than "going with your gut" or "just doing something" - or where evidence is simply not available, including many of our moral and religious "beliefs" (but not just those). If you are interested in this philosophical question, you might want to read the lesson provided by one of my colleagues for his version of the online class, which discusses James's position more in-depth, and which I have included as optional for anyone who is interested. (You will find it linked to in the weekly lesson folder. It is not necessary for you to read it; just providing it for those who are intrigued.)

Personally, I think that most of us already think more like Clifford's opponent, and that it is more adventurous to squarely face Clifford's moral challenge to us here.