The Allegory of the Cave

Be sure you understand

- What happens in Plato’s allegory

- What an allegory is

A story in which an extended metaphor, or series of interconnected symbols, can be interpreted as having a deeper meaning, unrelated to the symbols that make up the superficial story. Allegories are meant to convey insights of a moral or intellectual kind through fables that the audience can enjoy as stories. - Who Socrates was and how he died

Socrates was Plato's teacher and was sentenced to death for corrupting the youth of Athens, because he was always questioning everyone's authority. When they offered him his life if he would renounce his critical questioning, he chose to commit suicide instead. He famously said "The unexaminated life is not worth living. If he couldn't keep questioning appearances and trying to find out what was true he would rather die.

- What Plato considered to be the role of the teacher and how education works

Plato's Socrates says that a teacher can only turn students' attention in a different direction, away from more trivial or false things toward things that are more substantial or true. Once the teacher has shown these other realities to students, it is entirely up to the students whether they take them to heart or go back to ignoring them.

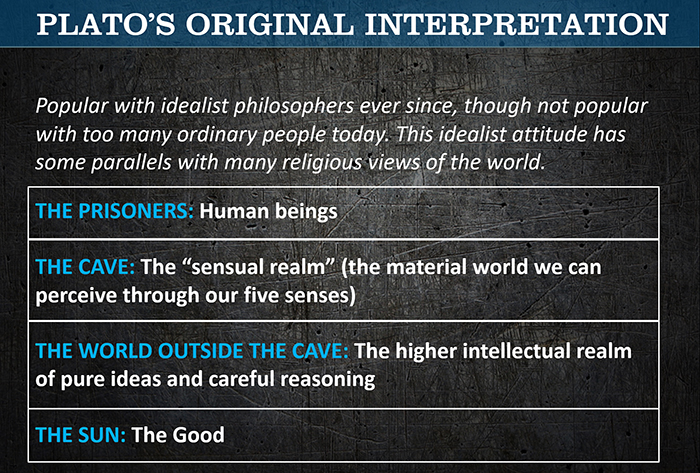

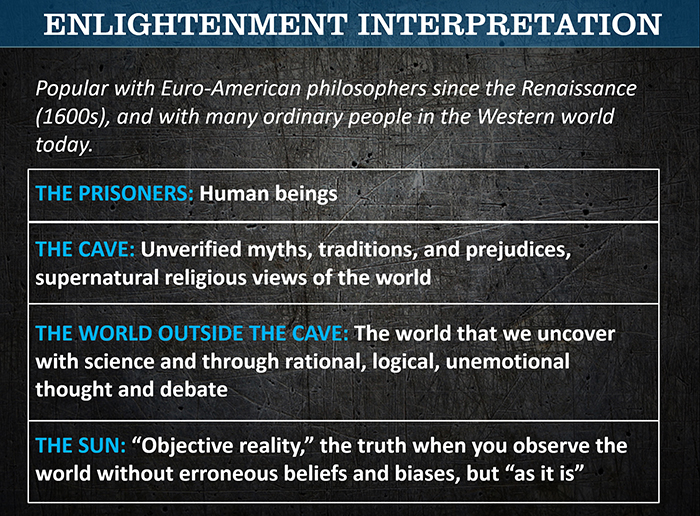

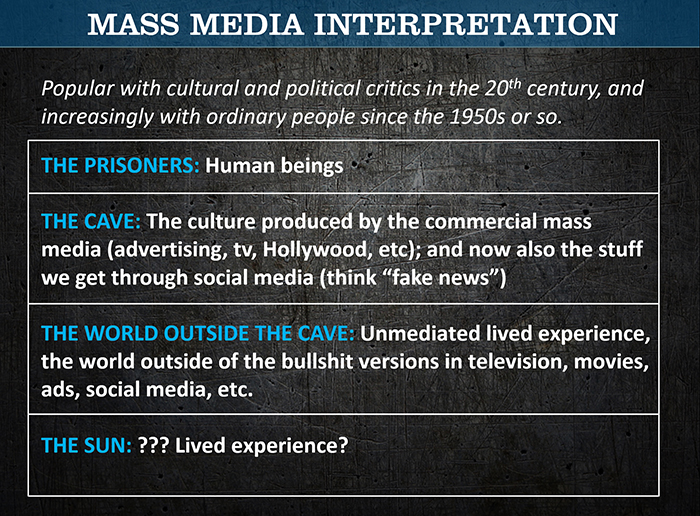

- Each of the three influential interpretations of the allegory explained below

Plato's original interpretation considers the cave to be the material world that is revealed to us through our senses. He believes there is a world of higher, more ideal true things (the world outside the cave) that you can attain through thinking, philosophical debate, and careful self-discipline. The highest truth, he thinks (the sun outside the cave), is "The Good."

The Enlightenment Interpretation would see the cave as the beliefs and traditions we were born into and have never questioned or tested. The world outside the cave is the material world we can sense and test. The way to leave the cave is to question our superstitions and practice a scientific approach to what is real: observation and experimentation to see if there is evidence for a belief. We should use rational though (logical, careful, and as unemotional as possible) to arrive at scientific truths we can share (the sun).

The Mass Media interpretation says that the cave is the world of media, the manufactured media and now our own social media. Media is often fictional or intentionally misleading, and it is always a reflection of reality (a shadow). The world outside the cave is presumably the world outside of media, the embodied world of real physical and social interaction in life.

Socrates and Plato

Do not leave Plato out in the sun, as he may become dry and inflexible.

Plato (around 427 B.C.E. - around 348 B.C.E.) is generally considered to be the first major Western philosopher whose written works have survived. He lived 400 years before Jesus and 1000 years before Mohammed. Plato’s teacher, Socrates, was an equally important philosopher, but nothing that he wrote has survived. We know about him through what other people have written about him, and mostly from the works of his student Plato.

Most of Plato’s works are presented as dramatic dialogues, and the main character in most of them is Socrates. Socrates, who does most of the talking in this reading, believed strongly in using the power of your mind to figure out what is true and what is illusion. He believed in truth and considered most of the people of his day to be fixated on illusions: religions, political fictions, erroneous philosophies, ideas of reality that were not really a good reflection of the higher truth of existence.

Socrates was famous for being a “sh!t-disturber” – a person who criticized anyone in power, anyone who claimed authority, anyone who thought he was smart. His typical method of attacking authority was simply to question it to its face. He would approach those with power and authority and ask them question after question about what their authority was based on, why they believed what they did, where their ideas came from - until eventually they wound up contradicting themselves, or getting confused, or not having any good answer, or just getting emotional and flustered. He wanted to show that everyone who was considered an authority and any belief considered authoritative is actually open to question and criticism.

Socrates was famous for being a “sh!t-disturber” – a person who criticized anyone in power, anyone who claimed authority, anyone who thought he was smart. His typical method of attacking authority was simply to question it to its face. He would approach those with power and authority and ask them question after question about what their authority was based on, why they believed what they did, where their ideas came from - until eventually they wound up contradicting themselves, or getting confused, or not having any good answer, or just getting emotional and flustered. He wanted to show that everyone who was considered an authority and any belief considered authoritative is actually open to question and criticism.

Cocktail party tip: The tactic of arguing with someone or teaching them something by asking them the right questions has come to be called "The Socratic Method." If somebody suggests using the Socratic Method, that's what they mean.

Many young people in Athens followed the philosopher Socrates, because he made the people in power look silly and encouraged the next generation to think for themselves and not just accept authority unthinkingly. Eventually those in power had Socrates arrested. One of the main charges was “corrupting the youth,” and Socrates was sentenced to death for his crimes against authority.

In some versions of his story he is offered a pardon if he will repudiate his teachings, admit he has been out of line, and promise not to cause any further trouble. He chose instead to drink poison and die. He claimed that “the unexamined life is not worth living.”

In the view of Socrates and his student Plato, most people are living unexamined lives: taking things as givens that we should be questioning or thinking more carefully and deeply about. Plato wants to encourage us to live not like animals or children, but like sane and reflective adult human beings, having considered alternative ways of seeing the world and made up our minds for ourselves about what is real and true, through careful thought and reflection.

Plato, “Allegory of the Cave.”

The Allegory of the Cave is part of a longer work by Plato, The Republic. But it is often studied on its own, because people have found it thought-provoking for 2400 years, regardless of the rest of Plato's arguments in The Republic.

If you haven't ever read or heard it, you may want to go through the Allegory of the Cave now. I have prepared a somewhat modernized and slightly paraphrased version of the translation presented in the official GNED 101 course reading. If you would prefer, you can scroll down to the end and watch the recording of me reading it aloud.

Plato, Allegory of the Cave, from The Republic, adapted for modern readers by Jim Nielson from the translation by C.D.C. Reeve

SOCRATES: If you want to understand education, I’d ask you to compare the effect of being educated versus not being educated to an experience like this. Imagine there are human beings living in an underground, cave-like place, with an entrance a long way up that is open to the outside world and as large as the cave itself. These people have been in this cave since childhood, with their necks and legs chained in such a way that they are stuck in the same spots, able to see only directly in front of them, because their restraints prevent them even from turning their heads around. Light is provided by a fire burning far above and behind them. Between the prisoners and the fire, there’s an elevated road running. Imagine that along this road a low wall has been built.

GLAUCON: Okay, I’m picturing it.

SOCRATES: Now also imagine that there are people travelling along this wall carrying all kinds of things that stick out above the wall. They’re carrying statues of people and animals, made of stone, wood, and other materials. Some of these carriers are talking among themselves and some are silent.

GLAUCON: It’s a pretty weird scenario you’re describing, and a strange kind of prisoners.

SOCRATES: They are like us. To begin with, do you think these prisoners have ever seen anything of themselves and one another apart from the shadows that the fire casts on the wall of the cave in front of them?

GLAUCON: How could they, if they can’t even turn their heads from side to side?

SOCRATES: What about the things being carried along the wall behind them? Wouldn’t it only be the shadows of those things that the prisoners have ever seen?

GLAUCON: Right.

SOCRATES: And if the prisoners could communicate with one another, wouldn’t they assume that the words they use apply to the shapes they see passing in front of them, not knowing that those are only shadows?

GLAUCON: They would have to.

SOCRATES: What if there was also a reverberation coming from the wall they’re staring at in this prison of theirs? When one of the carriers passing along behind them spoke, wouldn’t they assume it was the passing shadow that spoke?

GLAUCON: Yeah, I guess they would.

SOCRATES: All in all, then, what the prisoners would take for true reality is nothing but the shadows of those things being carried along behind their backs.

GLAUCON: It would have to be.

SOCRATES: Now think about what it would be like for them if they were somehow released from these bonds and cured of their foolish faith in the shadows. When one of them was freed and suddenly forced to stand up, turn his neck around, walk, and look up toward the light, he would find all these things painful, and he wouldn’t be able to see the things whose shadows he had seen before. The sudden brightness of looking directly toward the light would make it hard to see clearly. What would he say if we told him that what he had been seeing up till now had all been silly nonsense, but that now - because he is a bit closer to what is actually going on, and is turned toward things that are more substantial, he is seeing more correctly? And if we pointed to each of the things passing by on the road and demanded that he say what each of them is, wouldn’t he be confused at first, and still believe that the things he had seen earlier in the shadows were more truly real than the ones he was being shown now?

GLAUCON: Yes, he would still think the familiar shadows were the more real things.

SOCRATES: And if he were forced to look directly at the light of the fire, wouldn't it hurt his eyes and wouldn't he turn around and run back toward the things he can see comfortably, the shadows, and believe that they are more clear-cut than the new things he is being shown?

GLAUCON: He would.

SOCRATES: And if someone dragged him by force away from there, along the rough, steep, upward path, and did not let him go until he had dragged him out into the light of the sun, wouldn't he be hurt and angry at being treated that way? And when he came into the light, wouldn't he have his eyes filled with sunlight and be unable to see a single one of the real things in front of him?

GLAUCON: No, he would not be able to - at least not right away.

SOCRATES: He would need time to get adjusted, if he is going to see the things in the world above. At first, he would still see shadows most easily, then maybe reflections of things in water, and then eventually the things themselves in broad daylight. And it would be easier for him to look up at the sky at night, gazing at the light of the stars and the moon, than to look up at the bright sky and the sun during the day.

GLAUCON: Agreed.

SOCRATES: Finally, I suppose, he would be able to see the sun itself - not just reflections of it in water or some other place, but the sun just by itself in its own place - and be able to look up at it and see what it’s like.

GLAUCON: Yeah, I guess that’s right.

SOCRATES: And he would eventually be able to conclude that it provides the seasons and the years, governs everything in the visible world, and is in some way the cause of all the things that he and his fellows used to see down in the cave too.

GLAUCON: That would be the next step.

SOCRATES: What about when he thinks about his first dwelling place in the cave, and what had passed for wisdom down there, and his fellow prisoners? Don't you think he would count himself lucky that he had come into the light, and pity the others still down in the cave gazing at the shadows?

GLAUCON: Definitely.

SOCRATES: And if there had been honours or prizes among them for the one who was sharpest at identifying the shadows as they passed by; and was best able to remember which shadow usually came first, which often followed it, and which ones typically came along at the same time, with rewards for those who could thus foretell the future of the shadows, do you think that our guy on the surface would still want those rewards or envy those among the prisoners who were honoured and held power? Or wouldn’t he give anything to avoid their fate?

GLAUCON: Yes, I think he’d probably rather go through anything than live like that.

SOCRATES: So now think about this. If this guy went back down into the cave and sat down in his previous seat, wouldn't his eyes be filled with darkness, coming suddenly out of the sun like that?

GLAUCON: That’s right.

SOCRATES: And if he was forced to compete once again with the prisoners in recognizing the shadows, while his sight was still dim and before his eyes had recovered, and if it took some time for him to readjust to the darkness in the cave, wouldn't the other prisoners laugh at him? Wouldn't they say he had come back from his upward journey with his eyesight ruined, and that it was a waste of time even to try that journey? And as for anyone who attempted to free the other prisoners and lead them upward, if they could somehow get their hands on him, wouldn't they maybe even kill him?

GLAUCON: I guess they might!

[The Platonic interpretation starts here]

SOCRATES: Now think about it this way. The world revealed to us through our senses is like the prison dwelling, and the light of the fire inside there is a metaphor for the power of the sun in our material world. If you think of the upward journey and the seeing of things above as the upward journey of the soul to the realm of pure thought, you’ll get my point - since that’s what you wanted to hear about. God alone knows if this is true, but this is how it looks to me: in terms of things the mind can know, the last thing to be seen clearly is The Good, and it is seen only with lots of pain, hard work, and difficulty. Once you have seen it, though, you have to assume that it is the cause of all that is correct and beautiful in everything, that in the visible realm it produces both light and its source, and that in the mental realm it controls and provides truth and understanding; and that anyone who is to behave sensibly for their own sake or that of society has to be able to get to the point of seeing it.

GLAUCON: I agree, so far as I am able.

SOCRATES: Okay. Then join me in this further thought: you should not be surprised that the ones who get to this point are not willing to occupy themselves with everyday human affairs, but that, on the contrary, their souls are always eager to spend their time above. I mean, that is surely what we would expect, if the image I described before is also accurate in the realm of ideas.

GLAUCON: It is what you would expect.

SOCRATES: What about when someone coming from looking at higher things looks at the evils of everyday existence? Do you think it is surprising that he behaves awkwardly and appears completely ridiculous, if – while he has not yet adjusted to the darkness of ordinary life - he is expected, either in the courts or elsewhere, to compete in disagreements about the shadows of justice, or about the statues of which they are the shadows; and to disagree with the way these things are understood by people who have never perceived justice itself in its higher form?

GLAUCON: It is not surprising at all.

SOCRATES: No, anybody with a bit of common sense would keep in mind that our eyes can be confused in two ways and from two causes: when they go from the light into the darkness, or from the darkness into the light. If you imagine that the same applies to the soul, then when we saw a soul disturbed and unable to see something, we would not automatically make fun of them. Instead, we would try to figure out whether the soul had come from a brighter place and was dimmed through not having yet become accustomed to the dark, or from greater ignorance into greater light and was now dazzled by the increased brightness. We would consider the soul who had come from greater light happy in its experience and life, and feel sorry for the one still coming out of the darkness into greater light.

GLAUCON: That makes sense.

SOCRATES: If so, then here is how we must think about these matters: education is not what some people boastfully profess it to be. They claim that they can pretty much put knowledge into souls that lack it, like putting sight into blind eyes.

GLAUCON: Yes, they do seem to think it works like that.

SOCRATES: But here is what this story about the cave shows about this potential to learn that is present in everyone's soul, and the instrument with which each of us learns: the mind. Just as an eye cannot be turned around from darkness to light except by turning the whole body, so the mind must be turned away from the material world along with the whole soul, until it can stand to see what really is, and finally perceive the brightest real thing there is - what we call the good. Isn't that right?

GLAUCON: Yes.

SOCRATES: Of this, then-of this very turning in a new direction - there would be a craft concerned with how the instrument of the mind can most easily and effectively be turned around. It’s not about putting perception into someone’s mind. On the contrary, it takes for granted that perception is there, but not looking the right way, and it tries to redirect it appropriately.

GLAUCON: Makes sense!

Allegory

The story of the cave that Socrates tells to Glaucon is an allegory.

An allegory is a story in which an extended metaphor, or series of interconnected symbols, can be interpreted as having a deeper meaning, unrelated to the symbols that make up the superficial story. Allegories are meant to convey insights of a moral or intellectual kind through fables that the audience can enjoy as stories.

The cave story suggests a number of things about what it is like moving from a false sense of what is real to a more accurate understanding of reality. Giving up the version of reality you have been encouraged to believe in your whole life is painful, and may seem thankless. If you happened to grow up believing in Santa Claus – as many Western children do – when you find out that Santa is not real and it is actually your parents or caregivers who are filling the stockings, you may be disappointed; it may hurt; you may feel betrayed. You may think you were happier not knowing the truth. (Sorry if this is a spoiler for anyone.)

To take a more serious and adult example, if you have been raised your whole life in a culture that constantly reaffirms that Capitalism and Consumerism is the best and only viable way for humans to deal with their needs and desires, you may be reluctant to look at it from some other perspective.

It is difficult to give up what we have learned to trust and believe in, but the only way to get closer to truth and reality is to open our minds to alternative ways of seeing the world and explore them honestly and with careful thought, rather than knee-jerk emotions.

Another thing that the allegory of the cave suggests is that someone with a clearer knowledge of reality is often not appreciated by those who are still attached to their illusions. A person may gain insight into reality and be ignored by their friends or the rest of society, or even ridiculed or shunned, by those who still see things in the ways they have grown comfortable with.

So letting go of illusions and getting a clearer sense of what is true and real is painful, hard to do, and sometimes may seem thankless. But Plato (and the creators of GNED 101) still think you should try to find out what is true, even if it doesn't make you money or get you ahead in the world. Even if it makes you unhappy.

Why? Because humanity moves forward and improves and gets better at looking after itself by getting closer to the truth of reality. And the universe understands itself better, because humans are the only creatures we know of that can potentially understand themselves - and understand the rest of the universe. For Plato, knowing and understanding what is true is just plain Good, the ultimate Good with a capital G.

Three influential ways of interpreting the Allegory of the Cave

I’ve identified what I think are three of the most common and influential interpretations of the Allegory of the Cave. I would like you to consider and understand each of them, though you don’t have to agree with the “moral” of any of them, and you can make up your own interpretation and try to convince people that it makes just as good sense as any of these, or better sense. That would be a very philosophical thing to do, and some would say that reinterpreting the allegories humans have created is how the human race progresses.

But your interpretation has to make plausible use of all the details in Plato’s story: the cave, the outside world and the sun.

This might be a good place to mention an odd aspect of Plato's story: those people carrying objects along a road behind a wall behind the prisoners. People often jump to the conclusion that those people have imprisoned the chained-up shadow-gazers, and are showing them shadows to control and exploit them. But Plato never sees anything like that about him. I think the people carrying the objects are more like a metaphor for the living beings in our own world, of which we can only see what our senses can be perceive. I think Plato thinks that all human beings are trapped in the same cave really, and not kept prisoner there by bad actors who know the truth. Some people, however, may be able to make progress getting out of that cave. For Plato, those people will be philosopher

Influential Interpretation #1: Plato's original interpretation

Unlike most people in our society, Plato thought that what we call “the material world” was a false reflection of a higher reality. He called the material world “the sensual realm,” because we know it through our five senses. He believed that our minds can access the higher world of ideas and that we should not focus too much on what our senses tell us about physical existence. If you are an old-school Christian or Muslim, you may be able to relate to the idea of the material world as fallen and lesser. Some Eastern religions also suggest that what most of us call “reality” is an illusion, hiding higher or more true being.

We do know that the senses can fool us, and if we believe in science we can see ways in which the senses alone cannot always give us a valid picture of what is really going on. For religions, faith, obedience, and perhaps the inner heart lead to a reality higher than the world of our senses. For science, there are tools and technologies like the electron microscope that can show us things about reality that our unaided senses can’t. For Plato, rational thought is what will lead us out of the illusions of the material world to a higher truth, and ultimately, to “The Good.”

Plato’s point of view can be seen in the way Socrates himself interprets the allegory to Glaucon in the reading:

The world revealed to us through our senses is like the prison dwelling, and the light of the fire inside there is a metaphor for the power of the sun in our material world. If you think of the upward journey and the seeing of things above as the upward journey of the soul to the realm of pure thought, you’ll get my point - since that’s what you wanted to hear about. God alone knows if this is true, but this is how it looks to me: in terms of things the mind can know, the last thing to be seen clearly is The Good, and it is seen only with lots of pain, hard work, and difficulty. Once you have seen it, though, you have to assume that it is the cause of all that is correct and beautiful in everything, that in the visible realm it produces both light and its source, and that in the mental realm it controls and provides truth and understanding; and that anyone who is to behave sensibly for their own sake or that of society has to be able to get to the point of seeing it.

Influential Interpretation #2: The Enlightenment Interpretation

In the modern Western world there was an intellectual movement starting around 500 years ago called The Enlightenment that has greatly influenced how a lot of modern Canadians view the world. According to the Enlightenment, the way to know what is real is to ignore traditions, religions, etc and to use some combination of empiricism and rational thought to understand the world. Empiricism means observing nature and then deducing what is going on, with as little prejudice and pre-conceptions as possible. Rational thought means thinking carefully, logically, and unemotionally and analyzing ideas, theories, and opinions to understand their strengths, weaknesses, origins, and structure.

Plato is one of the heroes of the Western faith in rational thought. On the other hand, The Enlightenment’s focus on the necessity of observing nature through our senses seems less compatible with what Plato believed. The Enlightenment usually left any realm beyond the senses (a "higher" reality) aside; what it concentrated on was material reality. If Plato had lived long enough to see how science could extend our senses with telescopes, machines, mechanical sensors, geometry, and so forth, he might have agreed that our knowledge of the material world could be greatly increased, and he would have been glad to see a movement that tried to think carefully and clearly about reality, but the focus on material reality of the enlightement seems at odds with Plato's own idealism.

Influential Interpretation #3: The Mass Media Interpretation

This interpretation will probably be familiar to you. The mass media are the shadows on the cave wall, misleading us about the real world. What “the real world” means, in this interpretation, is less clear. If the media are full of lies, fictions, half-truths, misrepresentations, “spin,” etc, where do we find reality? Some would say that you can find it in some of the media; others might argue that the only reality that is really real is lived experience: one’s own unmediated experiences.

Education

Go back to the Allegory of the Cave for a minute. The actual topic that Socrates was trying to get Glaucon to think about was education.

Plato (through the mouth of Socrates) positions education as an attempt to draw your attention in a different direction from where it is focused, toward what is more real, the true, and the good.

It is “a craft concerned with how the instrument of the mind can be most easily and effectively turned around. It’s not about putting perception into your mind. On the contrary, it takes for granted that perception is there, but not looking the right way, and it tries to redirect it appropriately.”

The word "advertising" comes from the Latin for turning your attention. In a sense, advertising tries to draw your attention away from reality to look at "shadows" - the sneakers you "need" to achieve success, the products you consume to make yourself feel better. Perhaps Plato would suggest that education is trying to create "ads for reality." To draw your attention away from false things toward things that are more real or true or important (or even "good"!).

As Plato sees it, all a teacher can do is show you a way of seeing things that they consider more real. Your job in this class is to consider those ways of seeing things I show you, and then decide for yourself what you think. But Plato – and we GNED teachers – encourage you to use your understanding, your ability to think logically and not just emotionally, and your own good judgment to decide what is true. Avoiding the ideas altogether, not putting the work into understanding them, or just believing what you’ve always believed, what you want to believe, what your parents believe, or whatever, is not good enough in this class. You have to understand and think seriously about the ideas. Whatever you end up deciding you think about the material we expose you to, you do have to think about it to be doing education.

As Plato sees it, all a teacher can do is show you a way of seeing things that they consider more real. Your job in this class is to consider those ways of seeing things I show you, and then decide for yourself what you think. But Plato – and we GNED teachers – encourage you to use your understanding, your ability to think logically and not just emotionally, and your own good judgment to decide what is true. Avoiding the ideas altogether, not putting the work into understanding them, or just believing what you’ve always believed, what you want to believe, what your parents believe, or whatever, is not good enough in this class. You have to understand and think seriously about the ideas. Whatever you end up deciding you think about the material we expose you to, you do have to think about it to be doing education.

FOR TESTING

- What happens in Plato’s allegory

- What an allegory is

- Who Socrates was and how he died

- What Plato considered to be the role of the teacher and how education works

- Each of the three influential interpretations of the allegory explained below