A new economic paradigm

Be sure you understand

- Neoliberal globalized capitalsim and some of the concerns people have with it

- The meaning and significance of Bretton Woods

- Anthropocentrism vs biocentrism

- The two key flaws in the current economic paradigm according to Suzuki and Moola

- The idea of Environmental Rights

The climate vs capitalism?

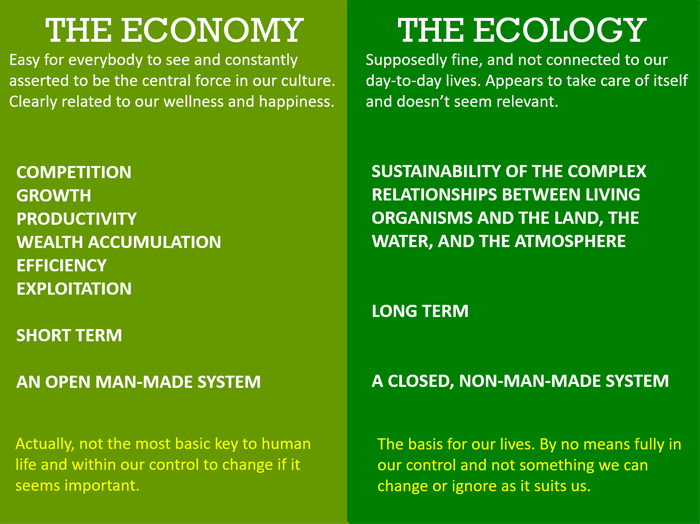

We've been looking at the climate crisis and capitalism because one idea that has been emerging during the last couple of decades is the possibility that there is a fundamental conflict between the workings of the giant nature-made system of nature and the giant human-made system of globalized capitalist economics. Many people think that we are not at a point where technology allows us to change nature to preserve the economic system, and therefore that the economic system will have to evolve to deal with the force of the system of nature. In the short assigned reading for this week, David Suzuki and Faisal Moola attempt to put the incompatibility of the two systems into the simplest terms possible.

A popular meme not too long ago.

Suzuki is a well-respected and influential Canadian environmentalist and broadcaster. He is probably best known for hosting the long-running CBC science series, The Nature of Things, which has been seen in more than 50 countries around the world. Suzuki is not an economist, but an ecologist. Still, in the brief article we will be looking at, he makes some simple observations that seem to strike at the fundamental assumptions of neoliberal economists. In the past, Suzuki has occasionally bluntly suggested that these economists are literally “insane.”

The neoliberal version of capitalism

Conservative British prime minister Margaret Thatcher popularized the slogan "There is no alternative" to affirm that capitalism was the only viable economic system. This seemed to be confirmed when the "communist" former Soviet Union collapsed in the late 80s.

In the second half of the 20th century the neoliberal version of capitalism became what most people in power in North America considered the norm, and was embraced by movers and shakers in other parts of the world as well. According to this version, capitalism should become the economic system of the whole planet - it will bring freedom, fairness, and prosperity with it. Globalization and free trade are good; everyone profits. The United States - the richest country in the world - is the model, the ideal. Every country in the world should try to follow the example of the United States: industrialization, wage labour, and trade across international borders. National governments should avoid regulating the marketplace; free trade on a global scale will lead to everyone enjoying the standard of living that people have in the United States, and similarly developed countries like Canada and most of Europe.

In the 1980s, three of the basic foundations of this neoliberal capitalist model were established: globalization (global free trade will profit everyone), "there is no alternative" (the idea that capitalism is the only viable economic system for human beings), and trickle-down economics (the idea that as the rich get richer, the wealth will naturally trickle down to everyone else as well).

The promise of capitalism seemed to be that every human being would eventually be able to live as well as the typical middle class American of the 1960s. That means they would have lots of private property, and could consume an endless range of products, and that everyone would just get richer as long as there was continued economic growth.

When I was a kid in California in the 1960s, this seemed perfectly plausible. Americans had never been more prosperous, especially middle class white Americans. My family was barely middle class, but we had a house, two cars, two tv sets and lots of new plastic toys at Christmas. It did indeed seem like things would just keep getting better.

Problems with globalized neoliberal capitalism

A serious part of the neoliberal system as it has played out in North America has been the "offshoring" of various kinds of labour to the developing world. On the one hand, this has meant cheaper labour costs for manufacturing and processing of goods, and this has kept the prices of consumer goods in North America down. But it comes with two kinds of human cost.

Workers in developing countries can be paid less than workers in North America and still enjoy better lifestyles than if they remained subsistence farmers in the countryside. But pay is low and working conditions are often gruelling and unsafe, and the work itself is often meaningless and alienated in the way Marx suggested. Most developing countries have less strict safety and health standards for workers than we have in Canada, and many of the people who produce our consumer goods are still living in what we would consider poverty. Think of the coffee growers with whom Aileen Herman lived, as discussed in her Politics reading.

Situations like the collapse of the sweatshop complex Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013 are well known. This was a giant building that housed a number of clothing factories, producing clothes for – among others – Joe Fresh, Benetton, and Walmart. Though cracks had been noticed in the structure, there were not enough safety regulations in place, and it was left to collapse one day, killing 1130 people and leaving 2500 injured.

Because so many major companies have become multinationals, we have a situation now where a company headquartered in Canada can outsource various parts of the production process to parts of the world where labour is cheaper, usually partly because they don't have the workers rights legislation in place that we have in Canada. This makes you and I - whether we know it or not - complicit in sweatshop labour abroad, whose products we enjoy at more affordable prices without generally having to think about where they come from.

Foxconn dorms rendered suicide-proof by barring the windows.

The situation at the Foxconn industrial park in China in 2012 is often used to dramatize the plight of the overseas workers who produce our products. Foxconn workers were involved in the manufacture of BlackBerry, iPhones, PlayStation, Xbox, Kindle, Wii, and similar devices. The workers lived in dorms on site. They worked long hours doing often meticulous and stressful work, and then went back to their dorms for a meal, a couple of hours of tv, and sleep, to do it all again the next day. In 2010, following 14 suicide-related deaths, a report that involved research by universities in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China described Foxconn factories as "labour camps" with widespread worker abuse. In 2012, 150 workers threatened to commit mass suicide to protest their working conditions. The workers were threatening to jump from the upper stories of their dorms. Rather than addressing their suffering, Foxconn's initial response was to install nets below, so that workers would not die if they jumped, or to put bars on the windows, so that they could not get out of the dorms to jump.

The complicity in worker suffering abroad is not the only problem that globalization has presented to Canadians. Part of the neoliberal rationale was that there would be a "trickle-down" effect in economics: as the rich got richer, the wealth would trickle down to enrich the rest of us as well.But in order to keep labour costs low, a lot of jobs that would have traditionally been available for Canadians have been offshored to developing countries. Many of the Canadian manufacturing jobs were unionized and well-paid with good benefits, and have now disappeared. Our consumer goods have remained cheap, even gotten cheaper, but our middle class has meanwhile also been shrinking for the last 40 years or so, and there seems to be a growing distance between the rich and the rest of us. The trickle-down effect has not apparently led to a growth in the middle and upper-middle class in North America. So critics argue that the wealth did not in fact trickle down - at least not to North Americans.

Is capitalism sustainable - or delusional?

Lots of ways of living together as human beings, lots of civilizations - the Mayans, the Egyptians, the civilization of the Indus Valley etc etc - have existed and then failed, and the capitalist world could be another empire on the brink of failure. Does the economic model make sense over the long term? Can it continue to evolve and adapt as it has for a few hundred years? What aspects of it are sustainable and what aspects are a threat to its own continued viability? Does capitalism need to adapt in new ways - humanist and environmental - in order to survive?

One worry people have started to have: the worry that our success with technology will make wage labour largely obsolete and there is nothing in the economic model as it exists to explain how a frighteningly large human population will be able to participate in the system if there are comparatively few jobs for them to earn wages for. Despite the fact that capitalism seems to drive technological innovation and that mechanization seemed to contribute to a better life for lots of people - not just the rich - the continued automation of the production of goods and services (and even creative work that may be taken over by artificial intelligence) would seem to lead to a world where human labour no longer has much value, and its hard to see the system we have now continuing to work for the good of the majority, if the majority have little to no wealth at all.

That same technological success has led to an environmental crisis, and again the argument that capitalism is the best system for everyone starts to look misguided if large numbers of people on earth are starting to suffer because of natural disasters that destroy property, claim lives, disrupt agriculture and food production, make traditional living places uninhabitable, and so forth.

Suzuki and Moola, in this week's reading, draw attention to the possibility that there are really two economies coming into conflict here: the economy of life on earth as a closed ecosystem, and the economy of capitalism, with its assumptions that resources, markets, and labour can go on expanding forever. The authors insist that we need a new global economic paradigm. The "old" paradigm (though it is really only a few hundred years old) is unfettered free market capitalism. Until recently, capitalism was considered by almost every Canadian to be the most important force that shapes our world, but the climate science suggests that there may be an even greater force to be reckoned with: Mother Nature.

A new economic paradigm

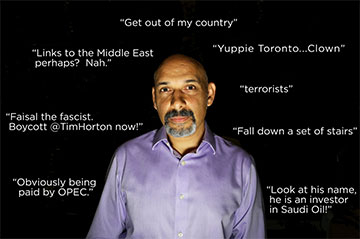

David Suzuki's co-author, UofT professor Faisal Moola, came in for racist attacks from pro-oil Twitter users in Alberta after he messaged Tim Hortons and thanked them for dropping ads by a company involved in pipeline projects.

The English word economy comes from Greek roots meaning "management of the household." When you think of the economy, it probably seems like it is all money, investments, standard of living, jobs, the "healthiness" and viability of corporations. But there are other factors to human health and well-being, indeed survival. Is capitalism still a viable model, or does the environmental crisis mean it has to go, or at least be seriously revised?

David Suzuki and Faisal Moola's brief statement of the matter is this week's assigned reading. You can read it on your own (it will take you 5-10 minutes!) or you can follow along with me here, to see what I make of it as I read it. Or both.

David Suzuki and Faisal Moola, "It's time for a new econmic paradigm," The Georgia Straight, August 18th, 2009.

I’ve heard economists boast that their discipline is based on a fundamental human impulse: selfishness. They claim that we act first out of self-interest. I can agree, depending on how we define self. To some, “self” extends beyond the individual person to include immediate family. Others might include community, an ecosystem, or all other species.

I list ecosystem and other species deliberately because we have become a narcissistic, self-indulgent species. We believe we are at the centre of the world, and everything around us is an “opportunity” or “resource” to exploit. Our needs or demands trump all other possibilities. This is an anthropocentric view of life.

Notice here the way Suzuki and Moola's attitude toward self parallels the indigenous worldview of "All my relations." The ideology of democracy+capitalism has generally seen the world as billions of competing individuals, each trying to get the best for themselves while largely ignoring the impact on others. This is only one way of seeing human beings (as selfish, competitive, and disconnected) and it is only one economic model that humans have lived by in the history of the world. Is it the last and best wisdom for how to live well, or is it more likely another false religion whose time has come?

Anthropocentric means "a way of looking at things where humans are at the centre of things, and the main thing you need to worry about is what humans say and do." As I said at the beginning of this lesson, many people are starting to see that our anthropocentric view of the world is a "reality bubble" that will eventually burst. It is foolish to think that what humans do on this planet is the only thing that matters, and that we are free to do anything because we are so powerful and smart. Elsewhere, Suzuki has characterized traditional and neoliberal market economists as "insane" in their tunnel vision, deeply detached from reality.

Thus, when faced with a choice of logging or conserving a forest, we focus on the potential economic benefits of logging or not logging. When the economy experiences a downturn, we demand that nature pay for it. We relax pollution standards, increase logging or fishing above sustainable levels, or (as the federal government has decreed [this was written in 2009]) lift the requirement of environmental assessments for new projects.

For a long time if economic growth and productivity (often assumed by ordinary people to translate into "jobs and prospertity") has come into conflict with environmental concerns, the econony "won." For example, the Trudeau government more recently gave a green light to the Trans Mountain pipeline in Alberta and B.C. despite the fact that science suggests we should leave any fossil fuels in the ground, not to mention the fact that there is quite a bit of resistance from indigenous groups, many of whose concern for their own land ties in with the broader interests of the environment in general. Trudeau promised that profits from the pipeline will be used to explore greener alternatives. When the government makes decisions like this, it is trying keep not just powerful corporations, but also voters happy. It is not thinking about protecting either the corporations or the voters from the consequences of their own short-sighted self-interest. It's easy for voters to understand their own economical predicaments, and hard for them even to be aware of how the environment works. Corporations are focused on their shareholders. Their concern is to maximize profits. Jobs and economic prosperity thus trump the realities of nature. And the politicians are often focused on their own selfish desire to maintain power. Thus, the environment seems secondary to all of them: voters, corporations, politicians.

Suzuki and Moola would call this attitude anthropocentric, as it treats reality as though the short-term success of particular human beings is the main thing, ignoring longterm sustainability, the people of the future, the rest of the people in the world right now, the rest of nature, and the future of the planet overall. Many now see this as a kind of blindness to reality at its most basic: the physical reality of the natural world that we are part of, and the reality of how life sustains itself in that world.

A fundamentally different perspective on our place in the world is called “biocentrism”. In this view, life’s diversity encompasses all and we humans are a part of it, ultimately deriving everything we need from it. Viewed this way, our well-being, indeed our survival, depends on the health and well-being of the natural world. I believe this view better reflects reality.

Here we see the question of "reality" again. For Suzuki and Moola, the abstract play of solely human economics are the shadows on the cave wall. The world outside the cave of capitalism is the more fundamental reality that we are first and foremost part of nature.

The most pernicious aspect of our anthropocentrism has been to elevate economics to the highest priority. We act as if the economy is some kind of natural force that we must all placate or serve in every way possible. But wait! Some things, like gravity, the speed of light, entropy, and the first and second laws of thermodynamics, are forces of nature. There’s nothing we can do about them except live within the boundaries they delimit.

But the economy, the market, currency – we created these entities, and if they don’t work, we should look beyond trying to get them back up and running the way they were. We should fix them or toss them out and replace them.

Some things are just real for Suzuki and Moola: laws of physics, for instance. Others are made up by humans - economics, for instance. Because humans invented the economy, we can change it, or toss the model out if it is coming into conflict with realities humans didn't invent and can't change. Ecology is the real "economy"; capitalist economics is an unreal way of managing the human household, which is still largely at the mercy of natural forces.

When economists and politicians met in Bretton Woods, Maine, in 1944, they faced a world where war had devastated countrysides, cities, and economies. So they tried to devise solutions. They pegged currency to the American greenback and looked to the (terrible) twins, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, to get economies going again.

Suzuki now talks about an economic summit held by the leaders of the capitalist world near the end of World War II, the Bretton Woods agerement. A new global monetary system was agreed upon, one that made the United States the standard for global currency and established America as the dominant power in the world economy.

The United States is one of the powers most committed to anthropocentric thinking about the economy. The thinking that all humans are selfish, each individual human is potentially against all others, and humans are the only thing we need to "deal with" to succeed are very common pre-assumptions of the form of liberal capitalist democracy that has now become the model of success to much of the rest of the world. (This really has only been the case for less than 100 years) By Suzuki's and Moola's reasoning, though, not every one of the eight billion people can become a well-to-do middle class American-style consumer. The things that make that impossible are not first and foremost laziness or lack of commitment; they are the limitations of the natural world, to endlessly provide for the greed of one species of primate.

The postwar era saw amazing recovery in Europe and Japan, as well as a roaring U.S. economy based on supplying a cornucopia of consumer goods. But the economic system we’ve created is fundamentally flawed because it is disconnected from the biosphere in which we live. We cannot afford to ignore these flaws any longer.

While acknowledging the success of America in the second half of the 20th century, Suzuki believes that the economic system that has been embraced by so much of the planet has two serious flaws, and that we are on the verge of discovering this the hard way if we aren't smart enough to recognize it intellectually.

Flaw 1: Beyond its obvious value as the source of raw materials like fish, lumber, and food, nature performs all kinds of “services” that allow us to survive and flourish. Nature creates topsoil, the thin skin that supports all agriculture. Nature removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and returns oxygen. Nature takes nitrogen from the air and fixes it to enrich soil. Nature filters water as it percolates through soil. Nature transforms sunlight into molecules that we need for energy in our bodies. Nature degrades the carcasses of dead plants and animals and disperses the atoms and molecules back into the biosphere. Nature pollinates flowering plants.

I could go on, but I think you catch my drift. We cannot duplicate what nature does around the clock, but we dismiss those services as “externalities” in our economy.

Free market capitalism ignores the parts of reality that seem to not be directly connected to its theory. The rest of nature is seen as an "externality" to the economy, and dismissed as irrelevant. Nature is seen by traditional capitalism the same way it sees everything - as a bunch of resources to be exploited for personal profit. If the environment is damaged or degraded by exploiting these resources, or simply can't keep up with the demand without collapsing, that is largely outside the scope of economics in the capitalist paradigm. But Suzuki and Moola think it will be disastrous to continue leaving the real "essential services" that nature provides out of our shared economic models, and we are already seeing some of the losses. These aren't financial losses; they're more fundamental than that. They're lives, and species, and ecosystems, including some of our own.

Flaw 2: To compound the problem, economists believe that because there are no limits to human creativity, there need be no limits to the economy. But the economy depends on having healthy people, and health depends on nature’s services, which are ignored in economic calculations. Our home is the biosphere, the thin layer of air, water, and land where all life exists. And that’s it; it can’t grow. We are witnessing the collision of the economic imperative to grow indefinitely with the finite services that nature performs. It’s time to get our perspective and priorities right. Biocentrism is a good place to start.

Biocentrism means considering life and the interconnectedness of all life first, before getting into what humans want and how they can get it. Free market capitalism demands unlimited growth if it is to work to everyone's advantage. Unlimited growth, forever. But there are actually very real limits to growth on our planet: natural ones. Natural resources are not infinite, new markets can't be manufactured out of thin air. Until we conquer space and perhaps colonize other planets where we can get new markets and resources and cheap labour, we are stuck in the limited space of the planet Earth, with its limited resources which are in a delicate balance that we rely on to be alive at all.

Ten years ago when the global economy was trying to recover from the 2008-9 scare, the buzzword was "economic growth." I don't know how many times I heard those words uttered with religious faith. But as a scientist, Suzuki believes that capitalist economics is a poor sort of science, because it is not holistic: endless economic growth is not sustainable within a limited natural world. The model may still work for some for a little while longer, but it is doomed to fail unless it can become more realistic about us being a part of nature, and nature having limits and not being irrelevant to our economy's continued success.

It’s time for a Bretton Woods II.

What Suzuki and Moola are saying in this final line is that there is an urgent need for the world governing agencies, including economists, to get together and come up with a more realistic and sustainable economic model than neoliberal capitalism. Any economic model that will actually be sustainable must move to a more biocentric view of reality. Obviously, it is not just the livelihood of Western capitalists that is at stake here - though ultimately they are at risk too - it is all human beings everywhere, and indeed many other forms of life.

One of the things that is rather clever about Suzuki and Moola's brief newspaper editorial is that it is not making a sentimental appeal to save the polar bears. Rather, it is speaking in terms of economic logic - a language the capitalists can understand. They are saying that the current model is not economically sustainable, because it does not take into its calculations the reality of the ecosystem and the physical limits on growth. Economists and legislators must become more realistic and include environmental factors in all of their economic calculations. For all our sakes, but also for their own. Needless to say, though. the capitalist mentality is generally focused on the short term: what will be profitable for me, regardless of the impact on anyone else, in my lifetime.

We see small signs that there may be some movement by our leaders and even corporate heads in the direction of making capitalism more sustainable and ecologically less destructive, such as the (much hated) carbon tax initiative, the interest in factoring "ecological credits" into the traditional economic exchange, and in steps some corporations have tried to take to include the environment more in their calculations, both for the sake of the profit of their shareholders and for the sake of optics. Maybe even in some cases for the actual good of the environment, since some CEOs also enjoy golfing and sailing and such!

The American Dream that has turned into the Global Ideal is that every human being can live like a king, and have more and more all the time. We are already seeing ways in which that might simply not be true. In America the rich have been getting richer and the poor have been getting poorer since the 1980s (in the postwar boom between 1945 and 1980 it did indeed look like everyone was going to keep getting richer, but that hasn't actually happened.) Very few people will be able to live like a king if the environment goes to hell. It will be a struggle for survival and a sad time for life on earth and a setback (at least!) for humanity in the slow crawl toward global and multicultural cooperation that we have made so far. With my limited knowledge of both economics and natural science, I am inclined to accept Suzuki and Moola's argument. I find many aspects of hyperexploitative and hyperconsumerist capitalism unattractive anyway; but the ecological argument seems to be one that goes beyond what we find appealing or not. The ecological argument is in a sense an "economic one": it's about how nature also implies an economy of costs, exchange, profits, and deficits. The reality of nature seems like a real showstopper to capitalism as a system for all, if it can't drastically evolve. We need a new economic paradigm.

Environmental Rights

The idea that environmental rights should be declared and pursued seems to be a relatively recent notion, but it is already well-known and even enshrined in the laws or constitutions of some countries, as well as being endorsed by the United Nations, of which Canada is a member. Environmental rights are not usually conceived of as the rights of the environment itself - such as the right of polar bears to have a place to live or of a specific coral reef not to be destroyed etc - but rather as an extension of human rights involving the right to a safe and stable environment. The Canadian Blue Dot Movement, for example, speaks of it this way:

Over the past 50 years, the right to a healthy environment has gained recognition faster than any other human right. The rights protected by a right to healthy environment include breathing clean air, drinking clean water, consuming safe food, accessing nature, knowing about pollutants and contaminants released into the local environment. (Blue Dot Environmental Rights statement)

The UN's definition is broader, not just about nature but also about the society in which one lives, but it includes both the basic right to "health, food and an adequate standard of living" and also "collective rights affected by environmental degradation, such as the rights of indigenous peoples."

The ways this concept relates to Climate Change should be obvious. The idea would be that if people in one part of the world are losing the ability to grow crops or are having their city submerged by rising sea water levels, it could be said that their environmental rights are being infringed upon or ignored. The same argument can be made - and has been - about situations where, for instance, overfishing of treaty waters by multinational fishing conglomerates makes it impossible for the indigenous people who supposedly have rights to those waters to sustain their lives in the traditional way.

Some universal human rights are widely accepted by most people in Canada. People should not be incarcerated without a trial; they should not be discriminated against on account of race or gender; they should not be turned into slaves, and so forth. These rights can be treated as distinct from environmental rights because they are more social and political - they are about how human beings treat one another. Nature is often thought of as a separate sphere, and Acts of Nature are usually considered to be outside of human control. But if humans in the form of individuals, corporations, or government are having an effect on the environment at large that makes life unsafe or untenable for people, perhaps this should now be seen as a human rights violation.

The conflict between different human rights can be well illustrated by the disagreements we have seen over how the COVID pandemic should be dealt with: arguments about restrictions, lockdowns, masking and vaccination, for instance. A virus like COVID-19 most definitely raises concerns about environmental rights. One student of GNED in a previous semester explained this well in their test answer:

Overall, it is essential to have environmental rights form a more prominent aspect of human rights legislation. It might be difficult because many people have thought of human rights as only relating to individual rights. However, we need to truly think about the benefits for everyone in the world. Like how COVID-19 has forced many people and governments to think about other people in other parts of the world, the climate crisis should do the same. Finally, the most important part is to understand how the whole world benefits when we are not greedy. One of the best solutions to COVID-19 is sharing vaccines fairly around the world to avoid variants from spreading and to avoid continuing this pandemic. We should think of the climate crisis similarly. If every person in every country, especially the rich people in rich countries, does their part, then the world would be a much better place and we can fight climate change successfully. We need to really change our thinking and make sure that this planet is healthy for everyone. (Nirojan Jeyarajah, GNED test answer, 2021)

Unfortunately, there is no global authority for the protection of any human rights. Human rights, including environmental rights, tend to be decided at the national level. That means, for example, that just as vaccination decisions in one country can affect virus transmission in others, so the the actions of a company headquartered in Canada can be directly responsible for terrible working conditions in another country, conditions that would be human rights violations in Canada. Similarly, actions being carried out by multinational companies in India - or by consumers of energy in Canada - could in fact have negative effects on the enviroment in other parts of the world, and thus on the lives of the people living in those countries.

For those who are interested in promoting human rights, environmental rights now loom very large, and there is an urgency to have them acknowledged and made a priority both at the national and the international level.