CULTURE AND Nature

Be sure you understand

- The meaning and significance of “all my relations” for the climate change topic

- What the David Suzuki Foundation says is the single most important step an individual can take to fight climate change.

- Why eating less meat would be a good thing (the whole story – overpopulation, methane, carbon release in production and transportation, normalization)

- The meaning of normalization and its relevance to personal action against the climate crisis.

- The difference between an anthropocentric and a biocentric view of life and reality.

- The meaning of normalization and its relevance to personal action against the climate crisis.

BACKGROUND TERMS

GREENHOUSE GASES

Gases that trap heat in the atmosphere. There are several different types of greenhouse gases, but two in particular are responsible for climate change: carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4).

FOSSIL FUELS

Coal, Oil, Natural Gas. Fossil fuels include coal, petroleum, natural gas, oil shales, bitumens, tar sands, and heavy oils. All contain carbon and were formed as a result of geologic processes acting on the remains of organic matter.

CARBON SINKS

A carbon sink is any natural or technological process that absorbs carbon from the atmosphere. Trees, soils and oceans are the most important natural carbon sinks, but all three are limited in the amount of carbon they are capable of absorbing.

This lesson talks about the climate crisis. The official Canadian Encyclopedia reading can tell you more about the current scientfic understanding of the crisis. This lesson comes at the topic from a slightly different angle: how some of the dominant human cultures relate to the realities of nature.

Reality bubbles

Nature is one of the most fundamental forces that shape our world. But it is very easy for us to lose sight of this. If you ask a typical Canadian what forces shape their world, they will likely start with economics and technology, and then may mention politics, or - if they are being a bit more critical in their thinking - maybe racism, privilege, or some other human ideological power-structure. Living in cities, focusing on jobs and school, interacting with other human beings and pets but with few other living things directly, and spending so much time consuming unreal images from technology, we are inclined to forget that we're part of nature.

If you would like to disrupt this blindness, I can recommend an entertaining and eye-opening book by science broadcaster Ziya Tong, The Reality Bubble (2019). Tong's book is a science-based onslaught on how delusional many of our ways of perceiving reality have become. Those of us in the developed world live in cities; our food comes to us packaged and processed, our garbage magically disappears once a week, our shit goes down the drain and we never have to think about it again. And of course, we spend a huge amount of our attention on distracting entertainment media and the seemingly inescapable work and economy that our technology has created for us and that our institutions - including Humber College - largely insist are the central focus of human existence.

But in fact - and the pandemic has helped some of us to grasp this - we are animals: vulnerable, mortal, physical - desperately dependent on the rest of life on earth, on the oceans, on the weather and the oxygen we breathe, on fresh water, on microorganisms within us and in the environment that even scientists don't fully understand - and all this is mostly hidden from us by the lives we have chosen to lead (perhaps we have chosen this way of living so we can avoid as much as possible the reality of what we actually are). The COVID-19 pandemic has been a wake-up call about some of this. Our lives are at risk not because we don't have a good enough paying job but because we're animals, and an invisible microorganism can change everything. In an effort to avoid the loss of human life and the collapse of our man-made health care systems, the economy can be drastically slowed down and we are forced to change our way of living because of this nasty little bug. I think there's a valuable lesson here about the basics of life, which privilged people in the wealthy nations of the world have largely been able to lose touch with.

Before the coronavirus and continuing alongside it we have the climate crisis. Most people are now vaguely aware that this poses a huge threat to our way of life, if not to our whole species and certainly other forms of life on earth. But the reality of the threat is very low for most of us, compared to the threat of FOMO or our chosen career being taken over by AI and robots.

Most of us know next to nothing about science; but science is a tool that allows us to see more of reality - non-human reality - than we can see with our eyes. If you recall Plato's original interpretation of his allegory it was that what we can know with our five senses are shadows of a fuller reality. The Enlightenment interpretation of the allegory said that science and rational thought were what could take us out of the cave of shadows. Most people have not bothered to go there.

We are not machines or computers; we are part of life, animals that are intimately connected to the rest of life on earth in a network of interdependent relationships.

European settler attitudes to nature

The culture we have inherited in North America comes from the white colonists who slowly pushed out and suppressed the people who were living here when they arrived: the indigenous people's of Turtle Island (one common indigenous way of referring to what the settlers called America).

The white Europeans were largely committed to a culture that revolved around "the three C's" of settler midset: colonization (settling and taking over land), Christianity (the "true" religion that should be shared with/enforced upon anyone who didn't have it), and commerce (Capitalism). The settler attitude to land and natural resources was to see them as resources to be exploited for capitalist gain and personal wealth. They believed in the private ownership of land (an attitude most indigenous people didn't understand or agree with), and that the land and non-human life were there to be exploited for profit (again, a very different attitude from how indigenous people saw their relationship to the rest of life).

Though colonization may now be complete and Christianity may have faded as a universal ideal, the attitudes of Capitalism toward the rest of life, the land, and the environment have persisted. We tend to see nature as something separate from us, and of which we are or should be "the boss." This is quite a central aspect of the invented human culture of Capitalism, and one that some people say is largely responsible for the risks we are at now from climate change.

All my relations

The invented human cultures of the indigenous peoples of Turtle Island tended to have a quite different attitude toward the relationship of human beings to the rest of nature. The Lakota people have a saying that has been adopted by many North American indigenous groups: "All our relations." This saying -sometimes a prayer, sometimes a greeting, sometimes a motto - acknowledges our deep connection to the rest of life and the fact that humans are really just one small part of life. Most of us city-dwellers in the Western world are almost wholly detached from that reality in our day to day existence. With our settler capitalist culture, we may see ourselves not as one form of life among many, but as human beings, separate from and above the rest of nature.

All my relations is a powerful counter-culture that is worth exploring. For one thing, it is closer to the reality-based culture of Western science than the capitalist attitude toward nature is. For another, it is arguably a more wholesome attitude to have toward the world we live in.

As the late Richard Wagamese wrote, this cultural attitude isn't just about the fact that you are related to your family or other people who you feel are part of your subculture. "Not just those people who look like you, talk like you, act like you, sing, dance, celebrate, worship or pray like you. Everyone. You also mean everything that relies on air, water, sunlight and the power of the Earth and the universe itself for sustenance and perpetuation. It's recognition of the fact that we are all one body moving through time and space together." ("'All my relations' about respect," Kamloops Daily News, June 11, 2013)

At a 2024 conference on environmentalism, 93-year-old Haudenosaune elder Oren Lyons made the point even more powerfully, perhaps. He said that in traditional indigenous cultures, people didn't see humans and special and the rest of nature as "wild." Rather they looked on nature, with themselves in it, as "a community." Imagine how our treatment of the enviroment might change if we all saw ourselves as a part of its "community."

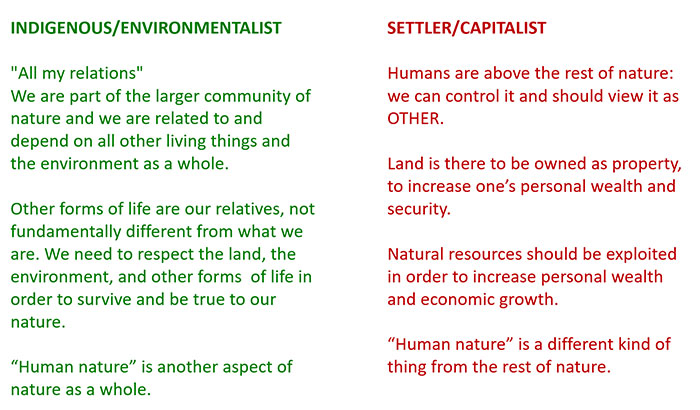

Two imaginary ways of conceiving humans beings and our relationship to the rest of nature

To summarize quickly the large incompatibility of the indigenous and settler ways of seeing reality, we could consider this table:

If we think of "reality" as something separate from human culture and not under our control, which of these ways of looking at our relationship to nature seems more "reality-based" to you

Our lack of attachment to the culture of science

If you would like to understand the background science a little better, you can start with the Canadian Encyclopedia article on Climate Change that is this week's reading, or if you don't have that much time you could at least watch this 4-minute video by popular science broadcaster Neil deGrasse Tyson.

In terms of this lesson, the most important point he makes is at the end: we can't SEE carbon dioxide. If we could actually see the CO2 we are releasing to the atmosphere, it might help us take the problem seriously. But our senses don't allow us to see, and without a much more solid grounding in science, it's hard for most of us to treat greenhouses gases a real.

Similarly, we have very little understanding of the connectedness of lifeforms, including at a microscopic level. So if we think of climate change as mainly ourselves having to deal with more extreme weather or hotter temperatures we are ignoring the hidden dangers than science could help us see. If we hear that some beetle, coral reef organism, or microbe in the soil may become extinct because of climate change, we may care little about this organism. But the organism is actually part of a great chain of interdepencies in the natural world. Its death may lead to other species not being able to survive, and a chain-reaction that could prove devastating for species we actually care about, such as coffee plants, chickens, or the trees that help keep us from all burning up.

What's wrong with global warming?

With the harsh Canadian Winters, global warming can sound like a positive thing. But it is as certain as science can be that if temperatures warm globally the way scientists are anticipating they will if we don't make changes, then the delicate balance of life on earth will eventually be catastrophically impacted. Scientists speculate (and already have some good evidence) that warming will lead to an ecological "domino effect" that makes parts of the world uninhabitable, destroys agricultural environments we currently rely on for food, drowns out coastal cities, entirely submerges small island countries, devastates animal and plant species, and throws us into an ecological crisis in which many human beings will suffer and die. (Leaving aside the suffering of all our non-human relations.)

If you wonder how you, living here in Ontario, will be affected, the answers are speculative but certainly still frightening. Assuming no radical action is taken and that you are still living in Ontario in 2050 much will likely have changed (in all things, obviously, but also in terms of the natural world, unless we slow or stop our greenhouse gas emissions). Ontario taken in isolation may be able to prosper from global warming. Our winters will be warmer, more of the land up north will be able to be farmed or inhabited by Canadians, etc. In terms of survival, if the Ontario of 2050 is similar to the Ontario of today only warmer, then Ontarians should be able to feed themselves and generate energy and enjoy the beach for longer. Assuming the rest of the world stayed the same as it is now and only Ontario warmed up, that is.

But Ontario is not an isolated island in the world. Other parts of the world could be finding agriculture impossible. Many people there will be struggling or dying. Many of the foods and other goods we are used to enjoying in Ontario may become unavailable, or too expensive for any but the wealthiest citizens. We must hope that our national borders are still respected, but I wouldn't count on that. Huge populations from countries around the equator where it is no longer possible to grow food will be streaming northward, looking for asylum. They will probably be desperate enough to by-pass legal immigration systems. A major military power may decide to invade Canada to get our relatively liveable land and still comparatively plentiful natural resources. We have a lot of water, a lot of farmable land, a lot of forests, fossil fuel reserves, and a comparatively small human population. We may not be able to maintain our soverignty in the face of critical problems like famine elsewhere in the world. Much of the world will probably be suffering and hungry. Some of it is heavily armed, and civilzed diplomacy seems to be increasingly dispensed with.

And of course, if one cares at all about those other human beings who aren't Ontarians, and other species who aren't human beings, then the results may seem ugly and wrong even if they don't affect us comparatively lucky Ontarians as much as they do others.

These scenarios are all speculation, a kind of science fiction really. But it is science fiction based in science fact and on the best guesses and computer projections that very smart people have been able to come up with. Environmentalists are still hopeful that humanity can be proactive, and fight against this potential crisis before it happens, rather than waiting until the eco system we have known for most of human history collapses and we decide that we have to do something because we are starving and dying, and killing each other for habitable land and food.

Who is responsible for the climate crisis?

This is a question that can be answered in a number of ways. All of us consumers are contributing to it, especially if we drive cars. The country that seems to be most drastically releasing CO2 and shows no sign of decreasing is China. India and other nations in the developing world are not part of UN efforts to curtail carbon release and do not typically have environmental protections as strong as those in Europe and North America.

Canada is only responsible for at most 2% of carbon emissions. Nevertheless, we are more of a problem than some countries because it is so cold here. We may have the highest per capita carbon footprints of any nationality. Another aspect of Canada that makes it play a bigger part than you might think is that we are one of the countries with the largest desposits of fossil fuels, and our decisions about whether to continue extracting them or not may influence other countries' readiness to make the painful move away from fossil fuels.

Corporations involved in manufacturing and distributing goods are a huge force in carbon release. If we did not have globalized supply chains and economic growth throughout the developing world, the carbon impact would be much less.

We can try to blame "the Billionaires" - and certainly they are blameworthy - but you and I as consumers are, ultimately, the reason for much carbon release in the world today.

What can you personally do about climate change

Assuming you believe that climate change is real, that it is caused by humans, and that it is dangerous for our future (and much of the other life on the planet) do you have any sense of what you personally could do if you wanted to fight against it?

When we've polled students in the past, the number one answer is often recycling. Unfortunately, recycling in its present state - though it is a good idea for other reasons - will do little to combat climate change. There are many other things we can do that are more likely to have a larger impact.

The Canadian broadcaster and environmentalist David Suzuki has a foundation whose web site discusses a number of actions worth taking. They can be broadly divided into political action and lifestyle/culture changes.

According to the David Suzuki Foundation, the number one thing an ordinary Canadian citizen can do to fight climate change is to engage in political action. If you care about making the climate safer, you should be voting for parties that prioritize this issue. Political action could also involve signing petitions, taking part in public demonstrations, writing to your members of parliament, and sharing information about such activity on your social media.

Lifestyle changes involve things like consuming less, reusing things, repairing things, driving less, and eating less meat. Some of these are discussed in more detail below. A single individual's lifestyle changes may have little impact by itself, but combined with millions of other single individuals changing, they will. An important aspect of changing your lifestyle is normalizing these lifestyle changes. The more people who shop thrift stores instead of fast fashion, the more people who go vegan, the more people who ride bikes, the more normal and "right" these activities will seem to others, and the more it becomes the standard for our society, instead of a seemingly crackpot fringe.

It is no exaggeration to say that our hyperconsumption habits in the "First World" and the ever-increasing manufacture of unnessary consumer goods in the developing world are major contributors to the current emergency. Most of our consumer goods in the contemporary world involve terrible impacts on carbon levels. Natural resources are destroyed; manufactuing burns coal or uses power that comes from carbon-releasing sources; we transport the products over incredible distances (all the way from China to Canada, for example); and the products are generally over-packaged in non-biodegradable plastic or paper that should either be composted or recycled but often isn't. The next time you buy a bag of candies, in which each candy has been individually wrapped in plastic, think about how much processing had to go into it and how much waste is involved - for what is also probably an unhealthy and unnecessary consumer good. (Does it even really taste all that great?) It may be good for the economy, but it is terrible for the ecology.

Thus, one of the 10 best things you can do on the list provided by David Suzuki's web site is Consume less. Of course, we have little else but consumption to bring meaning to our lives in the Western world, and we have been told that our consumption is necessary for the economy and that everyone will get richer the more we consume. This may be partly true for a time in a limited economic model, but as we'll see David Suzuki insists that it is no longer a sustainable model for our species.

Eat differently

A chicken-processiong and -packaging plant in China. Sometimes chickens are shipped from Canada to China for cheaper processing and then shipped back to Canada or to other parts of the world.

The factory production of meat and dairy has a huge impact on greenhouse gas emissions. Cattle produce enormous amounts of methane; forests are destroyed to create grazing land, removing natural carbon sinks (forests absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and thus reduce the greenhouse effect); and meat and dairy are processed and transported large distances in ways that add to the carbon footprint.

I am going to spend a little more time here on the "cheap meat" industry because it strikes me as a very clear example of humanity out of control - but in a way that is conveniently out of sight from the average citizen. In the book The Reality Bubble that I mentioned above, Ziya Tong takes the reader through a dizzying and nauseating survey of how the meat industry works so that everyone in a wealthy country like Canada can have cheap meat at every meal if they want to. I'll leave it to you to decide whether you want to know about the horrors that the animals endure - most of us would rather not know - but even just the scale at which meat production happens worldwide is monstrous:

Today, there are over one billion domesticated pigs on Earth, one and a half billion domesticated cows, and, according to annual slaughter numbers by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, almost sixty-six billion chickens. What this means, as George Musser, an editor at Scientific American, put it, is that “almost every vertebrate animal on earth is either a human or a farm animal.” Including horses, sheep, goats, and our pets, 65 percent of Earth’s biomass is domestic animals, 32 percent is human beings, and only 3 percent is animals living in the wild. (Tong 2019)

In other words, most of the animal weight on earth at present (97%) is human beings and the animals we have domesticated, mainly in order to eat them! This is one example of how radically humans have changed nature and diminished biodiversity.

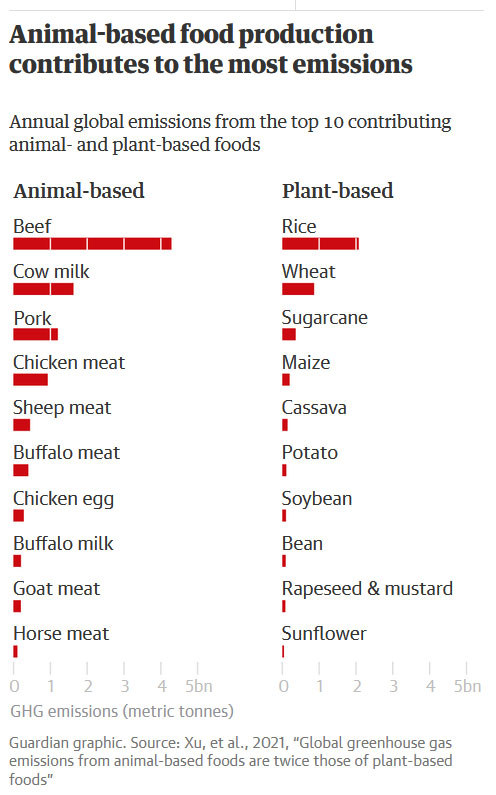

Source: Oliver Milman, "Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds," The Guardian Mon 13 Sep 2021.

A 2021 study publicized in The Guardian indicated that meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production. Cattle release huge amounts of the greenhouse gas methane in their burps and farts, and the factories and transportation that make make meat comparatively cheap are large contributors to carbon release.

The entire system of food production, such as the use of farming machinery, spraying of fertilizer and transportation of products, causes 17.3bn metric tonnes of greenhouse gases a year, according to the research. This enormous release of gases that fuel the climate crisis is more than double the entire emissions of the US and represents 35% of all global emissions, researchers said.

“The emissions are at the higher end of what we expected, it was a little bit of a surprise,” said Atul Jain, a climate scientist at the University of Illinois and co-author of the paper, published in Nature Food. “This study shows the entire cycle of the food production system, and policymakers may want to use the results to think about how to control greenhouse gas emissions.”

The raising and culling of animals for food is far worse for the climate than growing and processing fruits and vegetables for people to eat, the research found, confirming previous findings on the outsized impact that meat production, particularly beef, has on the environment. (Oliver Milman, "Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds," The Guardian Mon 13 Sep 2021)

The desire to provide everyone on the planet with a steady diet of meat protein has led to grisly overexploitation of animals and a mammoth impact on the levels of greenhouse gasses. We now find both environmentalists and animal rights activists encouraging everyone to reduce our meat consumption, avoid "cheap meat" (processed and/or mass marketed meat, such as is used in fast food, frozen and canned food, and generally in supermarket meat) and cheap dairy (which is also an industry full of cruelty with a significant impact on carbon levels). The ideal, according to environmentalists, would be for us to embrace veganism, or hugely reduce our dairy consumption and eat meat at most once or twice a week.

- Eat less meat and dairy; go vegan when possible

- If you do eat meat or dairy, buy local, organic, naturally raised products whenever possible

- Don’t waste food; consume more carefully

- Grow your own (I've done it; it's fun and really makes you appreciate what goes into the food we eat)

So, some things an individual can do: vote for climate action, spread the word, consume less, eat less cheap meat.

Normalization

The things individuals can do on their own or in small local groups are not completely insignificant, but they would probably never be enough to halt the crisis, unless everyone got on board with them.

However, to begin practicing these things (less consumerism, eating less meet, driving less) can also be important because it shows other people that these things can be done and are not even necessarily negative experiences. Thus, living more sustainably begins to become common in society and seems more normal.

Normalization is the cultural process through which new social norms evolve and become established. Norms change, and we can help them change. For instance, when I was a child in the 1960s, there was a huge number of people who smoked cigarettes. Smoking was considered "cool" by many people, cigarettes were advertised on television, and rarely would anyone even complain about second hand smoke.

Over the course of my life time, though, the norms around smoking evolved. Nowadays, comparatively few people still smoke cigarettes in Canada, people take seriously the health hazards of smoking and second-hand smoke, and the the government has restricted advertising of tobacco and made smoking look unappealing through packaging. People who smoke nowadays are often ashamed of it, try to hide it, sneak out, and avoid bringing second-hand smoke into the environments where other people could be affected by it (or even aware of it). In other words, the norms around smoking changed. Partly through the efforts of ordinary people and partly through more education and public messaging about the dangers of smoking.

The same thing could be done with things like hyperconsumption, over-consumption of cheap meat, driving gas-burning cars, and so on. These things could begin to seem yucky, and the norms could be changed, partly through some people adopting new norms around those things and showing people the way.

The climate vs capitalism?

As has already been suggested, one idea that has been emerging during the last couple of decades is the possibility that there is a fundamental conflict between the workings of the giant nature-made system of nature and the giant human-made system of globalized capitalist economics. Many people think that we are not at a point where technology allows us to change nature to preserve the economic system, and therefore that the economic system will have to evolve to deal with the force of the system of nature. In the short assigned reading for this week, David Suzuki and Faisal Moola attempt to put the incompatibility of the two systems into the simplest terms possible.

A popular meme not too long ago.

The English word economy comes from Greek roots meaning "management of the household." When you think of the economy, it probably seems like it is all money, investments, standard of living, jobs, the "healthiness" and viability of corporations. But there are other factors to human health and well-being, indeed survival. Is capitalism still a viable model, or does the environmental crisis mean it has to go, or at least be seriously revised?

David Suzuki and Faisal Moola's brief statement of the matter in the GNED 101 reading "It's time for a new economic paradigm." You can read it on your own (it will take you 5-10 minutes!) or you can follow along with me here, to see what I make of it as I read it. Or both.

David Suzuki and Faisal Moola, "It's time for a new econmic paradigm," The Georgia Straight, August 18th, 2009.

I’ve heard economists boast that their discipline is based on a fundamental human impulse: selfishness. They claim that we act first out of self-interest. I can agree, depending on how we define self. To some, “self” extends beyond the individual person to include immediate family. Others might include community, an ecosystem, or all other species.

I list ecosystem and other species deliberately because we have become a narcissistic, self-indulgent species. We believe we are at the centre of the world, and everything around us is an “opportunity” or “resource” to exploit. Our needs or demands trump all other possibilities. This is an anthropocentric view of life.

Notice here the way Suzuki and Moola's attitude toward self parallels the indigenous worldview of "All my relations." The ideology of democracy+capitalism has generally seen the world as billions of competing individuals, each trying to get the best for themselves while largely ignoring the impact on others. This is only one way of seeing human beings (as selfish, competitive, and disconnected) and it is only one economic model that humans have lived by in the history of the world. Is it the last and best wisdom for how to live well, or is it more likely another false religion whose time has come?

Anthropocentric means "a way of looking at things where humans are at the centre of things, and the main thing you need to worry about is what humans say and do." As I said at the beginning of this lesson, many people are starting to see that our anthropocentric view of the world is a "reality bubble" that will eventually burst. It is foolish to think that what humans do on this planet is the only thing that matters, and that we are free to do anything because we are so powerful and smart. Elsewhere, Suzuki has characterized traditional and neoliberal market economists as "insane" in their tunnel vision, deeply detached from reality.

Thus, when faced with a choice of logging or conserving a forest, we focus on the potential economic benefits of logging or not logging. When the economy experiences a downturn, we demand that nature pay for it. We relax pollution standards, increase logging or fishing above sustainable levels, or (as the federal government has decreed [this was written in 2009]) lift the requirement of environmental assessments for new projects.

For a long time if economic growth and productivity (often assumed by ordinary people to translate into "jobs and prospertity") has come into conflict with environmental concerns, the econony "won." For example, the Trudeau government more recently gave a green light to the Trans Mountain pipeline in Alberta and B.C. despite the fact that science suggests we should leave any fossil fuels in the ground, not to mention the fact that there is quite a bit of resistance from indigenous groups, many of whose concern for their own land ties in with the broader interests of the environment in general. Trudeau promised that profits from the pipeline will be used to explore greener alternatives. When the government makes decisions like this, it is trying keep not just powerful corporations, but also voters happy. It is not thinking about protecting either the corporations or the voters from the consequences of their own short-sighted self-interest. It's easy for voters to understand their own economical predicaments, and hard for them even to be aware of how the environment works. Corporations are focused on their shareholders. Their concern is to maximize profits. Jobs and economic prosperity thus trump the realities of nature. And the politicians are often focused on their own selfish desire to maintain power. Thus, the environment seems secondary to all of them: voters, corporations, politicians.

Suzuki and Moola would call this attitude anthropocentric, as it treats reality as though the short-term success of particular human beings is the main thing, ignoring longterm sustainability, the people of the future, the rest of the people in the world right now, the rest of nature, and the future of the planet overall. Many now see this as a kind of blindness to reality at its most basic: the physical reality of the natural world that we are part of, and the reality of how life sustains itself in that world.

A fundamentally different perspective on our place in the world is called “biocentrism”. In this view, life’s diversity encompasses all and we humans are a part of it, ultimately deriving everything we need from it. Viewed this way, our well-being, indeed our survival, depends on the health and well-being of the natural world. I believe this view better reflects reality.

Here we see the question of "reality" again. For Suzuki and Moola, the abstract play of solely human economics are the shadows on the cave wall. The world outside the cave of capitalism is the more fundamental reality that we are first and foremost part of nature.

The most pernicious aspect of our anthropocentrism has been to elevate economics to the highest priority. We act as if the economy is some kind of natural force that we must all placate or serve in every way possible. But wait! Some things, like gravity, the speed of light, entropy, and the first and second laws of thermodynamics, are forces of nature. There’s nothing we can do about them except live within the boundaries they delimit.

But the economy, the market, currency – we created these entities, and if they don’t work, we should look beyond trying to get them back up and running the way they were. We should fix them or toss them out and replace them.

Some things are just real for Suzuki and Moola: laws of physics, for instance. Others are made up by humans - economics, for instance. Because humans invented the economy, we can change it, or toss the model out if it is coming into conflict with realities humans didn't invent and can't change. Ecology is the real "economy"; capitalist economics is an unreal way of managing the human household, which is still largely at the mercy of natural forces.

When economists and politicians met in Bretton Woods, Maine, in 1944, they faced a world where war had devastated countrysides, cities, and economies. So they tried to devise solutions. They pegged currency to the American greenback and looked to the (terrible) twins, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, to get economies going again.

Suzuki now talks about an economic summit held by the leaders of the capitalist world near the end of World War II, the Bretton Woods agerement. A new global monetary system was agreed upon, one that made the United States the standard for global currency and established America as the dominant power in the world economy.

The United States is one of the powers most committed to anthropocentric thinking about the economy. The thinking that all humans are selfish, each individual human is potentially against all others, and humans are the only thing we need to "deal with" to succeed are very common pre-assumptions of the form of liberal capitalist democracy that has now become the model of success to much of the rest of the world. (This really has only been the case for less than 100 years) By Suzuki's and Moola's reasoning, though, not every one of the eight billion people can become a well-to-do middle class American-style consumer. The things that make that impossible are not first and foremost laziness or lack of commitment; they are the limitations of the natural world, to endlessly provide for the greed of one species of primate.

The postwar era saw amazing recovery in Europe and Japan, as well as a roaring U.S. economy based on supplying a cornucopia of consumer goods. But the economic system we’ve created is fundamentally flawed because it is disconnected from the biosphere in which we live. We cannot afford to ignore these flaws any longer.

While acknowledging the success of America in the second half of the 20th century, Suzuki believes that the economic system that has been embraced by so much of the planet has two serious flaws, and that we are on the verge of discovering this the hard way if we aren't smart enough to recognize it intellectually.

Flaw 1: Beyond its obvious value as the source of raw materials like fish, lumber, and food, nature performs all kinds of “services” that allow us to survive and flourish. Nature creates topsoil, the thin skin that supports all agriculture. Nature removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and returns oxygen. Nature takes nitrogen from the air and fixes it to enrich soil. Nature filters water as it percolates through soil. Nature transforms sunlight into molecules that we need for energy in our bodies. Nature degrades the carcasses of dead plants and animals and disperses the atoms and molecules back into the biosphere. Nature pollinates flowering plants.

I could go on, but I think you catch my drift. We cannot duplicate what nature does around the clock, but we dismiss those services as “externalities” in our economy.

Free market capitalism ignores the parts of reality that seem to not be directly connected to its theory. The rest of nature is seen as an "externality" to the economy, and dismissed as irrelevant. Nature is seen by traditional capitalism the same way it sees everything - as a bunch of resources to be exploited for personal profit. If the environment is damaged or degraded by exploiting these resources, or simply can't keep up with the demand without collapsing, that is largely outside the scope of economics in the capitalist paradigm. But Suzuki and Moola think it will be disastrous to continue leaving the real "essential services" that nature provides out of our shared economic models, and we are already seeing some of the losses. These aren't financial losses; they're more fundamental than that. They're lives, and species, and ecosystems, including some of our own.

Flaw 2: To compound the problem, economists believe that because there are no limits to human creativity, there need be no limits to the economy. But the economy depends on having healthy people, and health depends on nature’s services, which are ignored in economic calculations. Our home is the biosphere, the thin layer of air, water, and land where all life exists. And that’s it; it can’t grow. We are witnessing the collision of the economic imperative to grow indefinitely with the finite services that nature performs. It’s time to get our perspective and priorities right. Biocentrism is a good place to start.

Biocentrism means considering life and the interconnectedness of all life first, before getting into what humans want and how they can get it. Free market capitalism demands unlimited growth if it is to work to everyone's advantage. Unlimited growth, forever. But there are actually very real limits to growth on our planet: natural ones. Natural resources are not infinite, new markets can't be manufactured out of thin air. Until we conquer space and perhaps colonize other planets where we can get new markets and resources and cheap labour, we are stuck in the limited space of the planet Earth, with its limited resources which are in a delicate balance that we rely on to be alive at all.

Ten years ago when the global economy was trying to recover from the 2008-9 scare, the buzzword was "economic growth." I don't know how many times I heard those words uttered with religious faith. But as a scientist, Suzuki believes that capitalist economics is a poor sort of science, because it is not holistic: endless economic growth is not sustainable within a limited natural world. The model may still work for some for a little while longer, but it is doomed to fail unless it can become more realistic about us being a part of nature, and nature having limits and not being irrelevant to our economy's continued success.

It’s time for a Bretton Woods II.

What Suzuki and Moola are saying in this final line is that there is an urgent need for the world governing agencies, including economists, to get together and come up with a more realistic and sustainable economic model than neoliberal capitalism. Any economic model that will actually be sustainable must move to a more biocentric view of reality. Obviously, it is not just the livelihood of Western capitalists that is at stake here - though ultimately they are at risk too - it is all human beings everywhere, and indeed many other forms of life.

Reality-based culture?

The background idea of this week's lesson is that humans don't have control of the environment, but we do have some control of the cultures we have created, since we dreamt them up and we can use our imaginations to tweak, revise, or replace them.

I've been suggesting that the imaginary cultures of sciene and some aspects of indigenous wisdom might be more "reality-based" than the imaginary cultures of settle capitalism, nationalism, and other cultural inventions most of us take for granted in the modern world. What do you think of this idea? Is it possible we are doomed if we can't become more science-based in our understanding of what matters for human life, and more "community focused" in our understanding of our relationship to the rest of nature?