The Society of the Spectacle

Be sure you understand

- The Global Village

Marshall McLuhan's idea that electronic telecommunications media have turned the entire planet into one large community, a shared commons, a shared market, a shared consciousness. We can all be “with it” at the same time, instantaneously.

- The society of the spectacle (Guy Debord and the Situationists)

The phrase Society of the Spectacle draws attention to the way modern people in developed countries have gradually become passive spectators of media (eg watching tv, scrolling through TikTok) rather than doing things themselves in the real world. - Parasocial

A term for one-way imaginary "social" connections with influencers or fictional characters through media, as when someone "hangs out" with the characters in an episode of Friends, or "spends time with" a cottagecore influencer - Techno-utopian and techno-dystopian

Terms used to describe people their and attitudes polarized views on technology. A techno-utopian like Marhsall McLuhan or Elon Musk believes that more technology will lead to a better future and a better world. A techno-dystopian like Guy Debord may think that more technology is more likely to make things get worse.

This week's lesson looks at something almost everyone has thought and worried about at some point or other: how much time and energy we spend consuming visual media - streaming series, movies, ads, news, TikToks, YouTube videos, Instagram, etc etc etc. The lesson revives some arguments from 20th century culture critics, made before there was social media and mostly before the Internet, and asks you to think about those arguments and whether they could still be relevant or maybe even more important than ever in today's world.

Electronic sound and video media have only really been a thing for the last hundred years or so. Movies were being made for the public in the first decade of the 1900s and became more common during the 1910s. By the 1920s, they were big business and a common source of entertainment for many people in North America, Europe, and some other parts of the world.

Radio became common in the same general time frame, and phonograph records also came of age during the first two or three decades of the 20th century.

Television only became common in the 1950s. But by the 1960s, it was unusual Canadians of even lower middle class income not to have at least one television set in their homes. At one point during my childhood in the 1960s, we had three sets, one of them in my bedroom (I was a "spoiled" only child, at least in terms of consumer goods).

So from the beginning to the end of the 1900s, the average North American went from consuming no electronic media, to spending a lot of their time listening to radio and records, watching television and going to movies, and eventually surfing the web.

The Global Village

Around 1960, the groundbreaking Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan coined a phrase you have almost certainly heard: The Global Village. This was long before the Internet became a public thing. McLuhan believed that once humanity had invented the forms of electronic telecommunication that allowed almost instant communication across vast distances, the world had already become this Global Village. The telegraph in the 19th century, the telephone at the beginning of the 20th, and the broadcast technologies of radio and television had shrunk the world and brought us together in a way we had not been since we had lived together in small villages.

As with so much of what McLuhan proclaimed, the Global Village seems prophetic - even truer in our time than it was back in the 1960s when McLuhan was singing its praises. McLuhan is still fascinating to read today.

To get a taste of the world in which McLuhan was coming up with his theories, you might get a kick out of this this clip from the "Teenager" episode of the tv series CBC Explorations, originally aired May 18, 1960. The clothes, the haircuts, the pace are from 65 years ago, but many of McLuhan's observations ring prophetically true today. McLuhan starts talking around two and half minutes in, but whole thing is retro fun.

Here's the part of the interview where McLuhan talks about the distinction he sees between the "book man" of the past and "mass media man" of 1960:

I think the best distinction, Alan, might be found in the phrase “with it.” You know how we speak of being “with it”? Meaning we've understood completely. We've got the message, as it were, in every way possible. But in the older book or print culture people were not with it; they were away from it, by themselves, with their own private point of view. Now, you have no point of view when you're “with it” because you accept things totally. And we're “with it” because these new media of ours […] have made our world into a single unit. The world is now like a continually sounding tribal drum, where everybody gets the message all the time. A princess gets married in England. And boom boom boom go the drums. We all hear about it. An earthquake in North Africa. A Hollywood star gets drunk. Away go the drums again. I use the word tribal. It is probably the key word of this whole half hour. [ … ] I think you'll find everything we observe tonight about the media points in the direction of tribal man. And away from individual man. [ ... ] We're re-tribalising. Involuntarily we're getting rid of individualism. We're in the process of making a tribe.

The "individual" of the past, and the "tribal" participant of today; does this distinction make sense and stand up to careful scrutiny? Is "book man" entirely dead? And was the child of the tv age really "with it" as McLuhan suggests? "With it" seems to be the thing people who suffer from FOMO are trying to achieve.

Everyone on Earth can be "with it" now; but what exactly is it that we are with? Is it really important or that meaningful to know right away that a distant princess has gotten married, or that Zendaya has just had a wardrobe malfunction, or whatever? Why is that even a part of your reality? What impact can it have on you and your immediate world? Isn't it usually just more vicarious "entertainment," ultimately nothing to do with you - and nothing you can do anything with?

Reading or listening to him today, McLuhan seems mostly excited or neutral about the loss of individualism and "re-tribalisation" that the Global Village seemed to be bringing about. He seems to qualify as a techno-utopian, someone who believes technology will liberate humans, make them happier, solve our problems.

More dystopian views

Social critics have been concerned from the start about the rise in the consumption of "media" by their fellow citizens during the last hundred years (a tiny fragment of human history as a whole). It has often been argued that electronic media consumption has a tendency to dumb people down, compared - for example - to reading books, magazines and newspapers. Reading, it is assumed, encourages critical thinking, reflection, and the cultivation of one's imagination in ways that watching television may not.

Anti-capitalist critics meanwhile have argued that our entertainment media tend to be an extention of the consumerist demands for production of commodities that can be bought and sold for profit and that in turn reinforce the status quo of our capitalist worldview. Think of the multi-million dollar Hollywood movies, for instance, or the ads one had to watch on tv, or the subscription fees for streaming services. While a Netflix series may seem like an escape from the work one has to do all day, in many ways it is often no escape at all from the worldview that makes our work lives seem inevitable.

Isolation is another strange bi-product of our "communications" technologies. I often find it ironic that it is now our phones that make it easy for us to live in individualized isolated bubbles of unreality. The original phone, after all, was intended as a tool to communicate one human being with another in real time. It was two-way, and a form of virtual connection. But the "smartphone" is ironically an excellent means of disconnection (from real other people and lived experience). A medium is something between you and someone else. Originally, communications media were meant to make communication better between people. If I call my friend on the phone then ideally our communication will be as free of noise and manipulation as possible. But maybe the media we have created are actually something between us and reality (a buffer, a block) - even between us and each other. A screen.

Is it a good thing that many of us spend so much time viewing images and video in our lives these days? Is it a bad thing? Could it even be a dangerous thing for the future of humanity and democracy? These are some of the questions the writers we'll be looking at in the rest of this lesson are asking themselves - and us.

At the same time Marshall McLuhan was telling us we were now "with it," a group of politicized artists and activists in France were suggesting that we were getting further and further away from it, meaning from real human life and reality, all the time.

The Society of the Spectacle

I'm now going to tell you about a loose collective of artists and activists in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s who called themselves The Situationists. These people thought that the world in which everyone was working all day and then going home and watching tv on the couch all evening was a gross mistake. They were inspired by Marxist and post-Marxist critiques of Western culture in general, and argued that industrialization, consumerism, and the new broadcast media of the 20th century had perverted human relationships in an unhealthy and unnatural way.

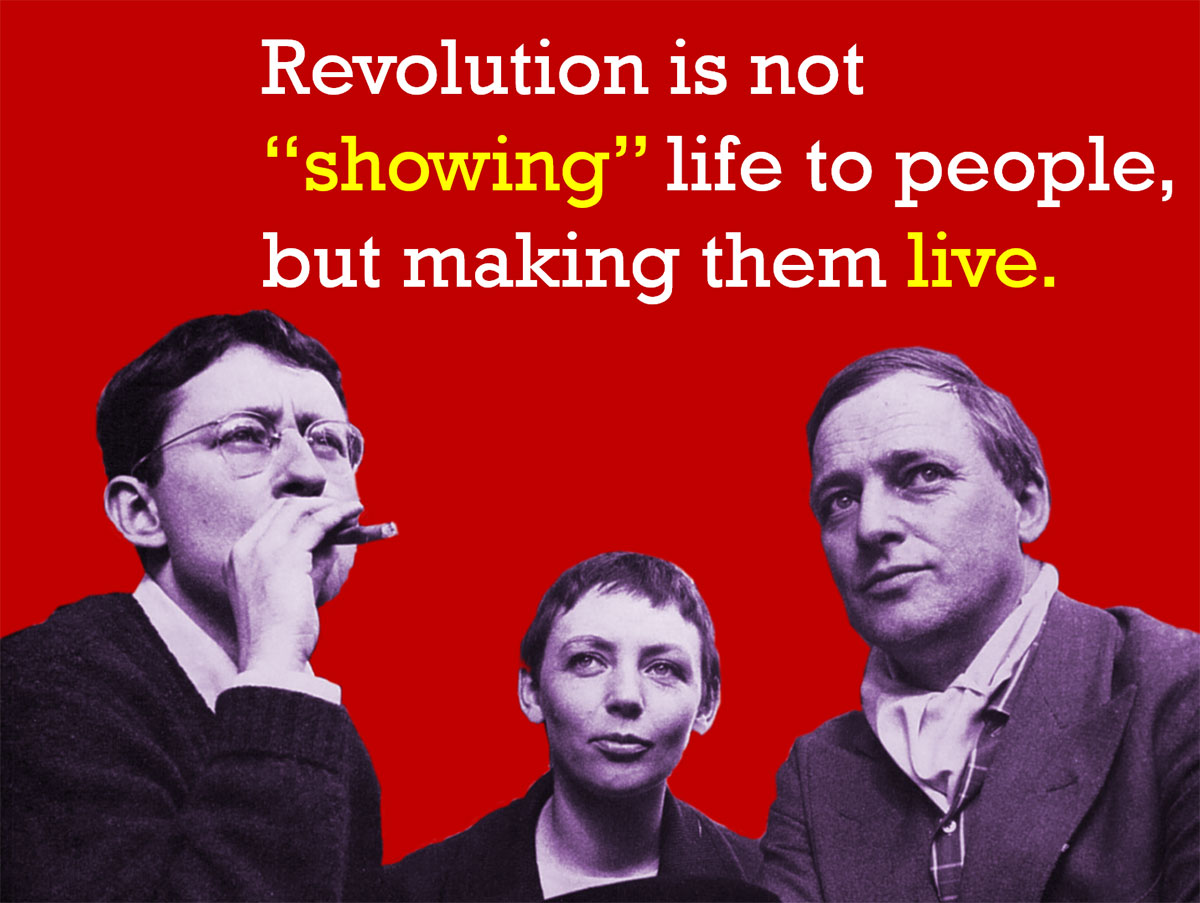

Guy Debord with two of his fellow artistic revolutionaries, Michèle Bernstein and Asger Jorn.

Previously our human relations had been directly with each other and with nature, but we now we increasingly related through manufactured objects and images. For these critics, "All that once was directly lived has become mere representation" (Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, 1967). In other words, all human life is now mediated by products and unreal fictional or fictionalized images. Products, consumer goods, brands, corporate and government propaganda, escapist fantasies, unrealistic materialistic ideals, partial images of reality created for the sake of entertainment or sensationalism - all of them manufactured for the rest of us by professionals working for companies who want to exploit us - had come to replace authentic social interaction, meaningful work, and creative leisure.

Guy Debord was the central Situationist. He and his fellow activists believed that "everyday life"- life lived with other people doing meaningful practical tasks like making meals or working together - doing labour that was meaningful in itself, producing something of material worth had been taken away from us. (Work that created something really material, like a loaf of bread, not "materialistic" like a designer garment or handbag). These ways of being they saw as the natural and healthiest state for the human animal. They argued that with the industrialization and compartmentalization of work and the invention of manufactured commodities, human life had changed - and not all for the better, as is commonly supposed.

The Situationists believed that the proliferation of endless images in mass media, clogging any clear view of non-mediated reality, had changed our human "reality." The emerging culture of television - which encouraged people to forgo social relationships in order to sit at home on their couches and watch packaged human interaction as a "show" - had brought about a "Society of the Spectacle." Most of us no longer engaged in life directly and participated in society out in the world very much: instead, we sat back as spectators in our living rooms and consumed the false "life" that was projected on our screens for us by the "culture industry" that creates the manufactured media of Hollywood, television, and so on.

Before the triumph of the Industrial Revolution, most human beings had experienced life directly and participated in it. We laboured to grow the food that we would later eat. When we were done working for the day, we ate dinner together, talked, played games together, made music for ourselves, went to church, worked in the garden, went for a walk, and so forth. We participated in culture and nature.

In the 20th century, however, people living in the developed and wealthy parts of the world were able (and encouraged) to experience life in a passive and non-participatory way, through consuming film and broadcast media, television, advertising, brands, images. Instead of playing sports, we sat and watched spectator sports on television. Instead of making music ourselves, we listened to music made by professionals on records or on the radio. Instead of doing a lot of things we would have done ourselves in the past, we sat back and watched a manufactured spectacle of "people" doing those things (or simulating doing things) on screens for our passive entertainment. We could feel that "life" was not something we were subject to ourselves, but something we were disconnected from, in control of (as long as we had the remote in our hands). The mass media was a crucial part of the consumer society. We were not just consuming products; we were consuming images of life, rather than fully living life ourselves.

The Situationists felt that the wealth of developed nations had led to a meaningless work life and alienated leisure time for the average human, filled with vicarious dreams of the "life" they saw on television and in ads. The Society of the Spectacle contributed to the emptiness of modern existence, because it made us passive, isolated and detached, empowered in our viewing but inadequate-feeling in real life, and driven to ever greater consumption and escapism, in hopes of somehow being "like the people on TV" rather than living our own lives realistically.

A more recent leftist critic of consumer culture, Noam Chomsky, has talked eloquently of how he personally believes humans actually want to do things, not just be spectators, and how he believes an incredible amount of energy has to be expended by Hollywood, advertisers, and other manufacturers of mass culture to convince us that the world represented in the media is fascinating and important and that we will find happiness and success in consuming commodities and mainstream entertainment products, living vicariously through consuming media.

I don't know whether I really believe that the working class people of Chomsky's youth read books and went to see Shakespeare plays, but I don't think he's just a nostalgic fool either. I do believe that most people are happier and feel more alive when they are doing something, creating something, accomplishing something (tinkering with an auto engine, say) than when they are watching other people do things as passive spectators.

Tomasz Fularksi, Pride 1

Of course now we have the vicarious spectacle of watching people do crafts on TikTok, rather than doing them ourselves. Instead of dancing, playing with a pet, having a live conversation with someone they know, many people prefer to connect with the semi-real "people" in their socials, who expect nothing immediately back from them. It is easy and often one-way, just like tv was.

In a sense, with the Internet we do have a much richer and more "real" vicarious spectacle to enjoy, from the comfort of our disengaged couchdoms. Does watching people make a meal or carve wood inspire us to do those things ourselves, or are we happy just to stand by and watch, consume without producing? Enjoy without participating. Partake, but only through voyeurism?

Vicarious enjoyment means watching or hearing about someone else doing something and somehow imaginatively identifying with them and getting some of the effects of doing it oneself, even though one isn't really doing anything (except sitting in a movie theatre, lying on a couch, or staring into a phone on a bus). It's strange, if you think about it, that people can lie on the couch watching a crime drama and get stimulated through some kind of vicarious identification with onscreen lovers, adventurers, action figures.

This vicarious identification is superbly satirized in the Simpsons "couch gag" sequence "LA-Z Rider" (a take off on the old tv series where a computerized car helped David Hasselhoff solve crimes (Knight Rider, 1982-1986)). Here, a motorized couch assists a fantasized version of Homer in experiencing a Miami Vice kind of exciting, sexy, fast-paced "life."

One of the reasons you may never have heard of the Situationists before is because unlike the artists you've heard of they didn't make a lot of art, and they weren't all that interested in "getting picked up by the media" and turned into a media phenomenon. They thought the media were evil. Because the media kept us from living our best lives in reality. Some people still study and use ideas from the Situationists (like me). One such "neo-Situationist" is Mackenzie Wark, who worries about how our media consumption is not just putting individuals at risk of wasting their lives, but is putting the planet at risk, because we are disconnected from the realities of nature by our consumerist and escapist media-dominted culture. So much of our sense of "reality" is actually media, and so little of our media tries to convey the actual reality of our existence as animals in a biological world. As Wark once put it, this “tool” of (post)capitalist media systems (streaming, social media, images and videos) may mean suicide for humanity, because the media cannot really deal with “the earth as the home from which it has expelled us.” I'll be coming back to this idea later in the term, when I talk about Climate Change.

Is "parasocial" life real life?

I want to turn to a topic that the Situationists didn't really discuss, but that I think relates to their concern that we are removed from where we want to be - alive - by our consumption of media.

I like to use the example of my own mother here when explaining what parasocial relationships are. I think these experiences relate to idea that we have drifted from real life interaction to mediated consumption in interesting ways. Maybe some of them are okay.

My mom spent the last ten years of her life living by herself in her house in the Seattle area, and she would spend most evenings with reruns of the television show Big Bang Theory back to back on syndicated tv. The characters on the show were her "best friends," or in any case they were the "people" with whom she spent the largest amount of time near the end of her life.

There is nothing that unusual about treating fictional TV characters as though they were real. Whenever someone says "Did you see what Sheldon did last night?!" they are immersed in the "fictional reality" of our modern world. Human culture is inherently like this - a mix of lived and mediated reality.

But is it possible that the greater replacement of social life by The Spectacle and the greater choice of virtual realities (video games, for instance) make our lives less really real all the time? And does that matter or not? What do you think?

Hanging out with some Friends

My mother watched Big Bang Theory because she wanted the illusion of some company in the house with her, and she liked the company of those characters. Sociologists call this kind of activity parasocial interaction, and unless they are in a judgmental or worried mood they don't necessary think of it as a negative thing. It can be "therapeutic" for many people, as long as they don't become obsessed or put themselves in a position to be exploited (by an influencer, say). Human beings can apparently get some of the same benefits they get from real live social interaction through the parasocial experience of watching Friends, for instance. Of course, they are being "social" with non-real (fictional) people and the "interaction" is not really interaction. It is one-way, and though you have been affected by these fictional characters from the 1990s, the fictional characters can in no way be influenced or changed by you: they are recorded images, they are fictional, they can't hear you or see you. Can we really call such interactions "social," or even "interactions"?

Isn't this another of our semi-real spectator activities? We can get real information about human interaction or understand the world better from watching sitcoms, of course. Or can we? The characters are realistic. Or are they? Do we care? Does this make us more real in the world? Does that matter?

It seems that most of us don't care. It's not so much that we don't know that Sheldon or Ross, Rachel, and so forth are fictional characters and not real people, as that we don't seem to care about this distinction as much as we might. We are used to spending a large amount of our time with non-real media projections, images on screens that look something like people. And they become a big part of our reality. Even if we "know they aren't real." (Do we? Really?)

What's more, now with the Internet we know "real people" (not fictional characters (?)) that we also experience frequently through the media (our friends on Instagram, for example, and people we have never met in real life whom we have friended or followed). Getting our "reality" in these mediated ways might make some of us (all of us?) less clear on the difference between (lived, embodied) reality and (spectated, framed/fictionalized/fictional) media. And as the simulation comes to look and feel more like reality itself (only "better"), or the simulation's "reality" comes to replace physical embodied reality for us more and more of the time, we seem to be less concerned about whether the things we love, the "people" with whom we get emotionally involved, or the situations on which we spend our time and energy are "real" in the old physical sense or not.

Is that okay? For us? For the rest of the world on whom we have an impact?

Are influencers real people and are their lives real lives?

With social media, more and more parasocial relationships can develop with "real" people (as opposed to fictional characters) we've never met, though these "real people" may have been doing their best to simulate the copies of real people simulated on fictional television or to seem like the non-fictional people who have a highly fictionalized representation there, such as celebrities. Do we remember (or care) how unreal all this really is? Maybe.

The parasocial relationships one has with Internet micro-celebrities or "influencers" can sometimes move into more genuinely interpersonal social relationships, when you contact them and they actually respond to your comments, send you an email, or mention you in a blog or a podcast or YouTube channel or TikTok. But there is still always a screen between us, a representation of an absent reality - editing, framing, simulation.

Reality tv, porn, lifestyle influencers. Real-life people as Spectacle. Real people as “entertainment products.” These are idealized and edited versions of life and of these people, so "not real" in some important sense. But at the same time they also really are those people at least in some sense and really are doing those things, even if they are doing them in front of a camera, and are thus also acting. So in a sense what we see is both real and simulated. Consumers of their media may complain that these images of real people are "unrealistic," but they continue to consume the images, partly because they aren't realistic, but rather consumable fantasy.

The basic idea is that the person represented in the video or images is a creation or presentation of the person behind the images, who is both a performer and a media producer, with all of the fictionalizing, and branding, etc that were part of 20th century manufactured media - and there's nothing wrong with that, as long as you understand that it's media and not reality.

French YouTube vlogger Alice Cappelle considers lifestyle vlogging as a "deal" similar to that between audience and creator in a movie theatre. We have agreed to meet in an unreal but emotionally satisfying "collision." She suggests that these hyperreal, parasocial kinds of media should be seen more as therapeutic art than spontaneous social interactions - or rather, she concludes that social interactions themselves may not revolve around authenticity so much as around this kind of emotional therapy and imaginary bonding:

... the exchange between a viewer and a creator is similar [to] that of a patient and a therapist, except that the experience and stories shared by the vloggers are as therapeutic for the audience as it is for themselves. [This] brings us back to the initial metaphor of the "deal": a movie, a book, a vlog is a place of collision of two imaginaries. The bond the creator and the viewer share is not based on authenticity, but on the emotion produced, crafted by the vlogger. In the end there is no such thing as authenticity. Just look for a second at the friendships you have in real life. We constantly edit our thoughts to make them fit social norms, social codes - to appear friendly, intellectual, intimidating. We all lie sometimes. and we behave differently depending on the people we're surrounded with at that precise moment. The result is that we are always unsure of what our true self is, which version of our self is the most sincere. For me, watching vlogs and bonding with vloggers has been a way to just escape for a bit, to discover a bit more about myself, and to project myself as well. It really feels empowering. (Cappelle 2021)

(Not on the test.) You can watch her whole video here if you want. The passage quoted above starts around 8:47.

Of course Cappelle is a vlogger herself; she knows well the imaginary power of this kind of "interaction," and relies on it at least in part for her living.

Many viewers, however, rather than treating the vlogs as self-extending fantasy/therapy/escape the way Capelle thinks we do, instead feel disempowered when their own real lives compare badly to the lives portrayed by their social media "cohort." We think that "this is what our life could be!" but never see the tedious aspects of the lives, the work that goes into that 20 minutes, the times they got their makeup wrong and had to re-shoot, the stress and burnout. The ways in which, even if they are being spontaneous and real, they are also always acting for the camera.

When the rest of us treat social media personas as our parasocial circle, we may well feel supremely inadequate, like the fat kid outside the high school clique (that was me!). If you think high school is a bitch, wait till you get on Insta and Tik Tok and Twerk (or whatever it's called). Now you're trying to fit in with semi-professional influencers who spend all their energy in presenting a larger-than-life identity. People didn't worry quite as much in the past, I suspect, (though some did) about not living up to the cuteness and wittiness of the characters on Friends or even not being able to keep up with the Kardashians, because on some level television was still acknowledged as not real life, fictional, staged, scripted, out there, made by giant corporations in Hollywood dreamland - not anything that could be confused with socializing with real people. Chapelle encourages us to see vlogs today in the same way, and not to worry about the parasocial escape some people are replacing embodied friendships with. Escape is therapeutic.

Social media is only sort of social. It is not social in the sense of being interactive spontaneous engagement with others most of the time. And much of it is not even about connecting to other individuals or groups, actually being social. What the major social media platforms tend to provide is a mediated mix of everything: social connection with people we know, glimpses of other people's reality and fantasy, news, political views, corporate media, edited photos, ads, absurdist videos, fiction, heartfelt activism, whacky escapism, oversharing, genuine communication, lies, fake news, and stuff your real-life friends really wanted to share with you. It is television plus us - exponentially. All presented in much the same way. No wonder we don't know what is real any more.

This partly also ties in with our continued television era readiness to accept any media as escapist entertainment. But now we are socializing and engaging in political action and communicating with our friends and families and strangers through our entertainment media. Media has thus become even more of a mix of serious, heartfelt, ironic, duplicitous, authentic, personal, shared, fabricated, manicured, raw, funny, heartbreaking, real and fake media, just like tv was only much more so. Does this make it more like life, or an even more seduction from being alive fully in the world?