A new economic paradigm

Be sure you understand

- The meaning and significance of Wetiko

- Enviro-realism

- The meaning and significance of Bretton Woods

- Anthropocentrism vs biocentrism

- The two key flaws in the current economic paradigm according to Suzuki and Moola

The climate vs capitalism?

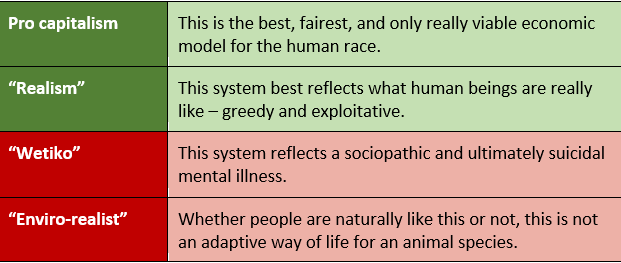

We've been looking at the climate crisis and capitalism because one idea that has been emerging during the last couple of decades is the possibility that there is a fundamental conflict between the workings of the giant nature-made system of nature and the giant human-made system of globalized capitalist economics. Many people think that we are not at a point where technology allows us to change nature to preserve the economic system, and therefore that the economic system will have to evolve to deal with the force of the system of nature. In the short assigned reading for this week, David Suzuki and Faisal Moola attempt to put the incompatibility of the two systems into the simplest terms possible.

A popular meme not too long ago.

Suzuki is a well-respected and influential Canadian environmentalist and broadcaster. He is probably best known for hosting the long-running CBC science series, The Nature of Things, which has been seen in more than 50 countries around the world. Suzuki is not an economist, but an ecologist. Still, in the brief article we will be looking at, he makes some simple observations that seem to strike at the fundamental assumptions of neoliberal economists. In the past, Suzuki has occasionally bluntly suggested that these economists are literally “insane.” This insanity could be compared to indigenous perspectives on Wetiko, which see the modern European worldview as a kind of mental illness.

Wetiko

Let's take a look at this idea before we get into the simple question of whether our economy and our ecology are ultimately incompatible. In the article "Seeing Wetiko: On Capitalism, Mind Viruses, and Antidotes for a World in Transition," Alnoor Ladha and Martin Kirk explain the idea:

Wetiko is an Algonquin word for a cannibalistic spirit that is driven by greed, excess, and selfish consumption (in Ojibwa it is windigo, wintiko in Powhatan). It deludes its host into believing that cannibalizing the life-force of others (others in the broad sense, including animals and other forms of life) is a logical and morally upright way to live.

Wetiko short-circuits the individual’s ability to see itself as an enmeshed and interdependent part of a balanced environment and raises the self-serving ego to supremacy. It is this false separation of self from nature that makes this cannibalism, rather than simple murder. It allows – indeed commands – the infected entity to consume far more than it needs in a blind, murderous daze of self-aggrandizement. Author Paul Levy, in an attempt to find language accessible for Western audiences, describes it as ‘malignant egophrenia’ – the ego unchained from reason and limits, acting with the malevolent logic of the cancer cell. We will use the term wetiko as it is the original term, and reminds us of the wisdom of Indigenous cultures, for those who have the ears to hear. (Ladha and Kirk 2016)

Francisco Goya, Saturn Devouring His Son (c. 1819–1823)

In other words, what is being suggested here is that the philosophy of individualism, competition, and pursuit of wealth is not the most sustaining and positive "religion" human beings have ever invented, but rather a delusional and deeply harmful disease of thought that has caused and continues to cause terrible suffering in the world. It is the paranoid delusion that each of us is disconnected from everyone else and the rest of our environment, and must control and exploit the others so as not to be destroyed by them.

Once you have played around with the idea that our way of life is a mental illness rather than the height of sanity and key to universal happiness, it's not that hard to see civilization itself, or at least Western civilization, as a dysfunctional syndrome that is spiralling out of control.

The pursuit of wealth at the expense of everything else has often struck me as somehow "paranoid" - an obsession. No one needs a billion dollars, and even a billion dollars doesn't ultimately make you safe, invulnerable, or immortal. I think both Marx and Freud would have also seen this kind of unreflective "need" for more as an illness. But it seems to be one of the main forces currently driving humanity.

I've certainly often acted in an impulsive way of this kind myself. I can never have enough books, for instance. I own many more than I will ever read. Somehow the book collecting satisfies some compulsion of mine. Is it really healthy, or is it a symptom of mental illness, my unconscious instinct that I can somehow protect myself if I surround myself with enough books? If I could be shown that this book collecting of mine was not a harmless or positive practice, but something doing harm to my fellow creatures and putting my own living environment at risk, would I be able to learn a new way of being? To borrow books from the library only when I want to read them, for instance? This is the kind of question intelligent people of all kinds are saying we may need to ask ourselves as human beings - including billionaires, but also you and me - if we are not going to cannibalize our own species, and destroy more of the other life that sustains us.

The ideals of capitalism do indeed involve the exploitation of the lives of others. In a certain sense, this could be seen as a kind of "cannibalism."

Enviro-realism

To look at Western civilization, individualism, and capitalism as aspects of a "mental illness" may sound farfetched, but it's worth considering the different ways the same things can be understood. What are human beings, what could we be, and what should we be, for the sake of ourselves and the rest of life on Earth?

What I'm calling the "enviro-realist" attitude here has long been argued by ecologists and scientists. For instance, Edward O. Wilson, an evolutionary biologist, wrote a short article in 1993 for The New York Times Magazine called "Is Humanity Suicidal?" In it he discussed the human race as an animal species that has gotten out of control. Our intelligence - supposedly what makes us above the rest of life - when coupled with our hard-coded survival instincts has led to a situation in which we can destroy our own environment, and probably will.

The human species is, in a word, an environmental abnormality. It is possible that intelligence in the wrong kind of species was foreordained to be a fatal combination for the biosphere. Perhaps a law of evolution is that intelligence usually extinguishes itself. This admittedly dour scenario is based on what can be termed the juggernaut theory of human nature, which holds that people are programmed by their genetic heritage to be so selfish that a sense of global responsibility will come too late. Individuals place themselves first, family second, tribe third and the rest of the world a distant fourth. Their genes also predispose them to plan ahead for one or two generations at most. (Wilson 1993)

Perhaps once humans got civilization with its excesss wealth, leisure time, etc, we were bound to go in directions that were deluded and unsustainable, still driven by our survival instincts which had evolved to deal with a difficult and fragile existence on the African savannah.

Biologists can show you examples of other species that have "lucked into" situations where their instincts led them to overexploit their own environment, ultimately making it unlivable for them. Examples of humans overexploiting closed systems on earth can also be seen. For instance, although there is room for debate, it has long been generally assumed that Rapa Nui, the incredibly remote island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean (popularly known as Easter Island), was once rich in trees and much more biodiverse. But then the island was deforested by the humans that eventually arrived there, possibly in order to facilitate the movement and construction of the giant stones used to create the mysterious heads that seem to have been part of the Islanders' self-expression as a civilization; meanwhile, the island's wildlife was overexploited, leading to a comparatively barren landscape today. For a balanced discussion, see Rethinking Easter Island’s Historic ‘Collapse’, but even if the eco-collapse scenario has been over-stated, the story it suggests is worth considering.

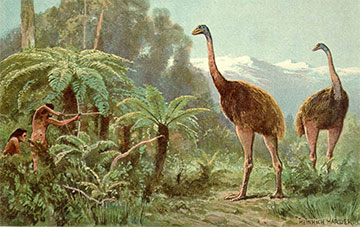

The moas, species of giant flightless birds that had lived in New Zealand for millions of years appear to have been hunted to extinction within 100 years of the arrival of human beings

When human beings arrived in New Zealand - which is assumed to have happened only about 700 years ago - the ecosystem of those islands began to be radically disrupted. New Zealand was probably largely wooded before man's arrival, and it had a large number of flightless bird species, because there were no land predators (so birds were safe to evolve into non-flying species) - until humans came. The arrival of human beings radically changed the biodiversity of New Zealand. As the Wikipedia article summarizes, "Since human arrival, almost half of the country's vertebrate species have become extinct, including at least fifty-one birds, three frogs, three lizards, one freshwater fish, and one bat." That's a lot of extinction to happen in 700 years.

Of course, people still managed to live in New Zealand, and when the Europeans arrived, they brought a bunch of species from Europe and other parts of the world as domesticated plants and animals. But if we think of Planet Earth as a much larger but finite island of this kind, we don't have anywhere else to get new species from to replace the ones we destroy ... We can't be sure what the overall effect on our enviroment will be if the mass extinctions caused by our activities continue. We may have cattle to eat, but little fertile land to grow food for the cattle on, for instance.

The environmental argument against human exploitation of resources centres around the fact that our planet itself is a closed ecosystem, just like these islands were, and that humans' superior intelligence and use of tools has now made it possible for us to over-exploit the resources to the point where the ecosystem could collapse, making it impossible for the 8 billion people on earth to live in the luxury we are all striving for and probably in many cases even to survive (quite apart from the damage other species are suffering because of us).

So one can perhaps see how our combination of (outdated) survival instincts and the competitive edge of intelligence and tools (technology) could ultimately prove to be toxic from an evolutionary point of view, even if it isn't necessary to think of it as "mental illness." The question for these enviro-realists is whether human intelligence can become proactive enough to ensure a healthy future for the species, rather than a return to a world where everyone is struggling for survival because of our own out-of-control instincts and, ironically, our unusual technological tools that allow unprecedented over-exploitation of our living environment.

Is capitalism sustainable - or delusional?

Lots of ways of living together as human beings, lots of civilizations - the Mayans, the Egyptians, the civilization of the Indus Valley etc etc - have existed and then failed, and the capitalist world could be another empire on the brink of failure. Does the economic model make sense over the long term? Can it continue to evolve and adapt as it has for a few hundred years? What aspects of it are sustainable and what aspects are a threat to its own continued viability? Does capitalism need to adapt in new ways - humanist and environmental - in order to survive?

In the lesson on Capitalism I suggested one worry people have started to have: the worry that our success with technology will make wage labour largely obsolete and there is nothing in the economic model as it exists to explain how a frighteningly large human population will be able to participate in the system if there are comparatively few jobs for them to earn wages for. Despite the fact that capitalism seems to drive technological innovation and that mechanization seemed to contribute to a better life for lots of people - not just the rich - the continued automation of the production of goods and services (and even creative work that may be taken over by artificial intelligence) would seem to lead to a world where human labour no longer has much value, and its hard to see the system we have now continuing to work for the good of the majority, if the majority have little to no wealth at all.

That same technological success has led to an environmental crisis, and again the argument that capitalism is the best system for everyone starts to look misguided if large numbers of people on earth are starting to suffer because of natural disasters that destroy property, claim lives, disrupt agriculture and food production, make traditional living places uninhabitable, and so forth.

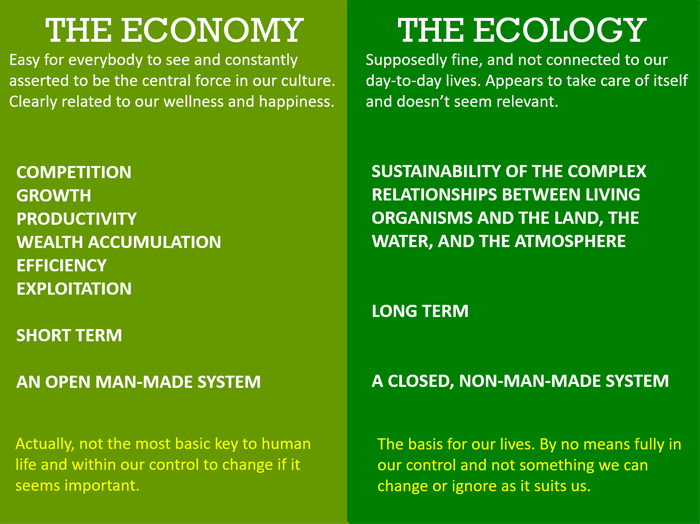

Suzuki and Moola, in this week's reading, draw attention to the possibility that there are really two economies coming into conflict here: the economy of life on earth as a closed ecosystem, and the economy of capitalism, with its assumptions that resources, markets, and labour can go on expanding forever. The authors insist that we need a new global economic paradigm. The "old" paradigm (though it is really only a few hundred years old) is unfettered free market capitalism. Until recently, capitalism was considered by almost every Canadian to be the most important force that shapes our world, but the climate science suggests that there may be an even greater force to be reckoned with: Mother Nature.

In "Is Humanity Suicidal?" written almost 30 years ago, Edward O. Wilson had been cautiously optimistic:

My short answer – opinion if you wish – is that humanity is not suicidal. ... We are smart enough and have enough time to avoid an environmental catastrophe of civilization-threatening dimensions. But the technical problems are sufficiently formidable to require a redirection of much of science and technology, and the ethical issues are so basic as to force a reconsideration of our self-image as a species. (Wilson 1993)

Suzuki and Moola think the time is running short, and that capitalism is one of the things we need to reconsider as a species. Starting yesterday.

A new economic paradigm

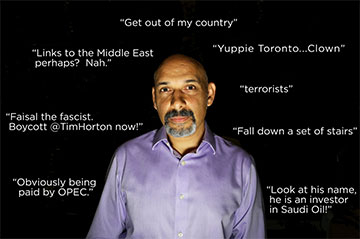

David Suzuki's co-author, UofT professor Faisal Moola, came in for racist attacks from pro-oil Twitter users in Alberta after he messaged Tim Hortons and thanked them for dropping ads by a company involved in pipeline projects.

The English word economy comes from Greek roots meaning "management of the household." When you think of the economy, it probably seems like it is all money, investments, standard of living, jobs, the "healthiness" and viability of corporations. But there are other factors to human health and well-being, indeed survival. Is capitalism still a viable model, or does the environmental crisis mean it has to go, or at least be seriously revised?

David Suzuki and Faisal Moola's brief statement of the matter is this week's assigned reading. You can read it on your own (it will take you 5-10 minutes!) or you can follow along with me here, to see what I make of it as I read it. Or both.

David Suzuki and Faisal Moola, "It's time for a new econmic paradigm," The Georgia Straight, August 18th, 2009.

I’ve heard economists boast that their discipline is based on a fundamental human impulse: selfishness. They claim that we act first out of self-interest. I can agree, depending on how we define self. To some, “self” extends beyond the individual person to include immediate family. Others might include community, an ecosystem, or all other species.

I list ecosystem and other species deliberately because we have become a narcissistic, self-indulgent species. We believe we are at the centre of the world, and everything around us is an “opportunity” or “resource” to exploit. Our needs or demands trump all other possibilities. This is an anthropocentric view of life.

Notice here the way Suzuki and Moola's attitude toward self parallels the indigenous worldview of "All my relations." The ideology of democracy+capitalism has generally seen the world as billions of competing individuals, each trying to get the best for themselves while largely ignoring the impact on others. This is only one way of seeing human beings (as selfish, competitive, and disconnected) and it is only one economic model that humans have lived by in the history of the world. Is it the last and best wisdom for how to live well, or is it more likely another false religion whose time has come?

Anthropocentric means "a way of looking at things where humans are at the centre of things, and the main thing you need to worry about is what humans say and do." As I said at the beginning of this lesson, many people are starting to see that our anthropocentric view of the world is a "reality bubble" that will eventually burst. It is foolish to think that what humans do on this planet is the only thing that matters, and that we are free to do anything because we are so powerful and smart. Elsewhere, Suzuki has characterized traditional and neoliberal market economists as "insane" in their tunnel vision, deeply detached from reality.

Thus, when faced with a choice of logging or conserving a forest, we focus on the potential economic benefits of logging or not logging. When the economy experiences a downturn, we demand that nature pay for it. We relax pollution standards, increase logging or fishing above sustainable levels, or (as the federal government has decreed [this was written in 2009]) lift the requirement of environmental assessments for new projects.

For a long time if economic growth and productivity (often assumed by ordinary people to translate into "jobs and prospertity") has come into conflict with environmental concerns, the econony "won." For example, the Trudeau government more recently gave a green light to the Trans Mountain pipeline in Alberta and B.C. despite the fact that science suggests we should leave any fossil fuels in the ground, not to mention the fact that there is quite a bit of resistance from indigenous groups, many of whose concern for their own land ties in with the broader interests of the environment in general. Trudeau promised that profits from the pipeline will be used to explore greener alternatives. When the government makes decisions like this, it is trying keep not just powerful corporations, but also voters happy. It is not thinking about protecting either the corporations or the voters from the consequences of their own short-sighted self-interest. It's easy for voters to understand their own economical predicaments, and hard for them even to be aware of how the environment works. Corporations are focused on their shareholders. Their concern is to maximize profits. Jobs and economic prosperity thus trump the realities of nature. And the politicians are often focused on their own selfish desire to maintain power. Thus, the environment seems secondary to all of them: voters, corporations, politicians.

Suzuki and Moola would call this attitude anthropocentric, as it treats reality as though the short-term success of particular human beings is the main thing, ignoring longterm sustainability, the people of the future, the rest of the people in the world right now, the rest of nature, and the future of the planet overall. Many now see this as a kind of blindness to reality at its most basic: the physical reality of the natural world that we are part of, and the reality of how life sustains itself in that world.

A fundamentally different perspective on our place in the world is called “biocentrism”. In this view, life’s diversity encompasses all and we humans are a part of it, ultimately deriving everything we need from it. Viewed this way, our well-being, indeed our survival, depends on the health and well-being of the natural world. I believe this view better reflects reality.

Here we see the question of "reality" again. For Suzuki and Moola, the abstract play of solely human economics are the shadows on the cave wall. The world outside the cave of capitalism is the more fundamental reality that we are first and foremost part of nature.

The most pernicious aspect of our anthropocentrism has been to elevate economics to the highest priority. We act as if the economy is some kind of natural force that we must all placate or serve in every way possible. But wait! Some things, like gravity, the speed of light, entropy, and the first and second laws of thermodynamics, are forces of nature. There’s nothing we can do about them except live within the boundaries they delimit.

But the economy, the market, currency – we created these entities, and if they don’t work, we should look beyond trying to get them back up and running the way they were. We should fix them or toss them out and replace them.

Some things are just real for Suzuki and Moola: laws of physics, for instance. Others are made up by humans - economics, for instance. Because humans invented the economy, we can change it, or toss the model out if it is coming into conflict with realities humans didn't invent and can't change. Ecology is the real "economy"; capitalist economics is an unreal way of managing the human household, which is still largely at the mercy of natural forces.

When economists and politicians met in Bretton Woods, Maine, in 1944, they faced a world where war had devastated countrysides, cities, and economies. So they tried to devise solutions. They pegged currency to the American greenback and looked to the (terrible) twins, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, to get economies going again.

Suzuki now talks about an economic summit held by the leaders of the capitalist world near the end of World War II, the Bretton Woods agerement. A new global monetary system was agreed upon, one that made the United States the standard for global currency and established America as the dominant power in the world economy.

The United States is one of the powers most committed to anthropocentric thinking about the economy. The thinking that all humans are selfish, each individual human is potentially against all others, and humans are the only thing we need to "deal with" to succeed are very common pre-assumptions of the form of liberal capitalist democracy that has now become the model of success to much of the rest of the world. (This really has only been the case for less than 100 years) By Suzuki's and Moola's reasoning, though, not every one of the eight billion people can become a well-to-do middle class American-style consumer. The things that make that impossible are not first and foremost laziness or lack of commitment; they are the limitations of the natural world, to endlessly provide for the greed of one species of primate.

The postwar era saw amazing recovery in Europe and Japan, as well as a roaring U.S. economy based on supplying a cornucopia of consumer goods. But the economic system we’ve created is fundamentally flawed because it is disconnected from the biosphere in which we live. We cannot afford to ignore these flaws any longer.

While acknowledging the success of America in the second half of the 20th century, Suzuki believes that the economic system that has been embraced by so much of the planet has two serious flaws, and that we are on the verge of discovering this the hard way if we aren't smart enough to recognize it intellectually.

Flaw 1: Beyond its obvious value as the source of raw materials like fish, lumber, and food, nature performs all kinds of “services” that allow us to survive and flourish. Nature creates topsoil, the thin skin that supports all agriculture. Nature removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and returns oxygen. Nature takes nitrogen from the air and fixes it to enrich soil. Nature filters water as it percolates through soil. Nature transforms sunlight into molecules that we need for energy in our bodies. Nature degrades the carcasses of dead plants and animals and disperses the atoms and molecules back into the biosphere. Nature pollinates flowering plants.

I could go on, but I think you catch my drift. We cannot duplicate what nature does around the clock, but we dismiss those services as “externalities” in our economy.

Free market capitalism ignores the parts of reality that seem to not be directly connected to its theory. The rest of nature is seen as an "externality" to the economy, and dismissed as irrelevant. Nature is seen by traditional capitalism the same way it sees everything - as a bunch of resources to be exploited for personal profit. If the environment is damaged or degraded by exploiting these resources, or simply can't keep up with the demand without collapsing, that is largely outside the scope of economics in the capitalist paradigm. But Suzuki and Moola think it will be disastrous to continue leaving the real "essential services" that nature provides out of our shared economic models, and we are already seeing some of the losses. These aren't financial losses; they're more fundamental than that. They're lives, and species, and ecosystems, including some of our own.

Flaw 2: To compound the problem, economists believe that because there are no limits to human creativity, there need be no limits to the economy. But the economy depends on having healthy people, and health depends on nature’s services, which are ignored in economic calculations. Our home is the biosphere, the thin layer of air, water, and land where all life exists. And that’s it; it can’t grow. We are witnessing the collision of the economic imperative to grow indefinitely with the finite services that nature performs. It’s time to get our perspective and priorities right. Biocentrism is a good place to start.

Biocentrism means considering life and the interconnectedness of all life first, before getting into what humans want and how they can get it. Free market capitalism demands unlimited growth if it is to work to everyone's advantage. Unlimited growth, forever. But there are actually very real limits to growth on our planet: natural ones. Natural resources are not infinite, new markets can't be manufactured out of thin air. Until we conquer space and perhaps colonize other planets where we can get new markets and resources and cheap labour, we are stuck in the limited space of the planet Earth, with its limited resources which are in a delicate balance that we rely on to be alive at all.

Ten years ago when the global economy was trying to recover from the 2008-9 scare, the buzzword was "economic growth." I don't know how many times I heard those words uttered with religious faith. But as a scientist, Suzuki believes that capitalist economics is a poor sort of science, because it is not holistic: endless economic growth is not sustainable within a limited natural world. The model may still work for some for a little while longer, but it is doomed to fail unless it can become more realistic about us being a part of nature, and nature having limits and not being irrelevant to our economy's continued success.

It’s time for a Bretton Woods II.

What Suzuki and Moola are saying in this final line is that there is an urgent need for the world governing agencies, including economists, to get together and come up with a more realistic and sustainable economic model than neoliberal capitalism. Any economic model that will actually be sustainable must move to a more biocentric view of reality. Obviously, it is not just the livelihood of Western capitalists that is at stake here - though ultimately they are at risk too - it is all human beings everywhere, and indeed many other forms of life.

One of the things that is rather clever about Suzuki and Moola's brief newspaper editorial is that it is not making a sentimental appeal to save the polar bears. Rather, it is speaking in terms of economic logic - a language the capitalists can understand. They are saying that the current model is not economically sustainable, because it does not take into its calculations the reality of the ecosystem and the physical limits on growth. Economists and legislators must become more realistic and include environmental factors in all of their economic calculations. For all our sakes, but also for their own. Needless to say, though. the capitalist mentality is generally focused on the short term: what will be profitable for me, regardless of the impact on anyone else, in my lifetime. Wetiko.

We see small signs that there may be some movement by our leaders and even corporate heads in the direction of making capitalism more sustainable and ecologically less destructive, such as the (much hated) carbon tax initiative, the interest in factoring "ecological credits" into the traditional economic exchange, and in steps some corporations have tried to take to include the environment more in their calculations, both for the sake of the profit of their shareholders and for the sake of optics. Maybe even in some cases for the actual good of the environment, since some CEOs also enjoy golfing and sailing and such!

The American Dream that has turned into the Global Ideal is that every human being can live like a king, and have more and more all the time. We are already seeing ways in which that might simply not be true. In America the rich have been getting richer and the poor have been getting poorer since the 1980s (in the postwar boom between 1945 and 1980 it did indeed look like everyone was going to keep getting richer, but that hasn't actually happened.) Very few people will be able to live like a king if the environment goes to hell. It will be a struggle for survival and a sad time for life on earth and a setback (at least!) for humanity in the slow crawl toward global and multicultural cooperation that we have made so far. With my limited knowledge of both economics and natural science, I am inclined to accept Suzuki and Moola's argument. I find many aspects of hyperexploitative and hyperconsumerist capitalism unattractive anyway; but the ecological argument seems to be one that goes beyond what we find appealing or not. The ecological argument is in a sense an "economic one": it's about how nature also implies an economy of costs, exchange, profits, and deficits. The reality of nature seems like a real showstopper to capitalism as a system for all, if it can't drastically evolve. We need a new economic paradigm.

FOR TESTING

- Wetiko

- Enviro-realism

- Anthropocentrism vs biocentrism

- The two key flaws in the current economic paradigm according to Suzuki and Moola