Capitalism

Be sure you understand

- Capitalism and the briefly outlined development of it

- The Marxist critique of capitalism: Alienated Labour

- The Division of Labour and why Marx thought it was evil

- Postcolonial and social equity critiques of capitalism, including Angela Davis on the status of women

- Neoliberal assumptions about capitalism

- The problems raised by neoliberal globalization

- The concern about the future of wage labour in a world of Artificial Intelligence and robots

What is capitalism?

Often when I have mentioned capitalism in lectures, students have been brave enough to ask me just what capitalism is. I always assume that everyone knows, since it is the one ideological system we all share. Capitalism is the economic system in which we live, and as such it will seem to many to just be "reality" or at least "economic reality." Capitalism is the air we breathe, a successful ideology vying for the status of true universal world "religion." The one appeal I can probably make to everyone reading this is to say "this will make you (or save you) money" or "if you do that, you will gain (or lose) wealth."

But it should not be forgotten that capitalism is a human invention, not just "the natural state of the world." As the science fiction writer Ursula K. LeGuin once said:

We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art, the art of words. (Acceptance speech for the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, 2014)

Capitalism is an economic worldview based on private ownership of the parts of society that produce and distribute goods (e.g. factories or supermarkets) and the operation of those private enterprises for profit. Characteristics central to capitalism include private property, capital accumulation (amassing wealth), wage labor, voluntary exchange in marketplaces, a price system, and competitive markets. In a capitalist market economy, decision-making and investment are determined by the owners or shareholders who control enterprises, by the people running the banks, and by the economists and brokers who manage capital markets (stocks and currencies), while prices and the distribution of goods are mainly determined by competition in the market.

We have not always lived as capitalists. Though trade has always been a part of more complex "civilized" human societies, capitalism as we know it is a relatively new model for the majority of humanity, and it came to prominence in the "Western world" during the same period that saw the rise in science and technology and the exploration and colonization of large parts of the rest of the world by Europeans (1500-1900). Capitalism became a common aspect of most Western people's lives after the Industrial Revolution (which took place around 1750 - 1900). Since the 1800s industrialized Western capitalism has been spreading around the rest of the world more virally.

The logic of capitalism

In a capitalist organization of the economy, decision-making and investments are made by those who own or control "capital" (wealth, property, companies, shares in corporations), and prices and distribution of goods and services are theoretically set by competition in consumer markets. This is the basis of the system by which most trade happens in Canada, and also most trade between Canada and other parts of the world.

Looked at with a bit of distance, some of the most basic philosophical assumptions of modern Western capitalism go something like this: All humans are naturally selfish and want more (or maybe only some important humans are like that). Competition is a natural and reliable regulator of wealth distribution and exchange, and the fairest and best system for distributing wealth and goods in a complex society.

Competition: When humans compete for resources and consumer dollars it is good for everyone. Costs are kept down, jobs are created, everyone prospers. The best way to get humans to do better things is to put them in competition with each other.

Exploitation of resources, including human resources: A capitalist assumes that natural resources should be exploited, turned into products, and sold. This will give the capitalist profits, which can be put aside for their personal future and that of their family, as well as providing other people with work, income, and products.

Though capitalists might be less willing to talk about this part, there is also an assumption that it's natural or fine to exploit other human beings for the sake of one's own profit. A typical owner pays workers much less than the actual value of their work and scoops off that difference as profit. Sellers may also exploit vulnerable individuals and communities as consumer markets. The point is to make personal profit from resources, including human resources. But the assumption is that everyone wins by this system.

We have not always lived as capitalists

Detail from the painting Death and the Miser by Hieronymus Bosch. Source: Wikipedia.

Again, it is important to recognize that while there may have been small groups of capitalists in many civilized societies throughout history, we have not always all been capitalists the way we are today. In the Christian Middle Ages in Western Europe, for instance, there was no standard system of currency, and most people had no access to money or other forms of wealth. The vast majority of people didn’t own property or have any way of getting any, and there was almost no social mobility. Most people worked not for money, but simply raising food for themselves, to trade for other goods, and to contribute to the local nobleman in return for protection.

There were merchants in towns and some limited exchange through buying and selling. But for the majority of people at that time, amassing gold or other early forms of currency wasn't a possibility, and except in rare cases it wasn't considered the meaning of life. The nobles might feel it was incidental to their general power, which involved military strength. Money in itself wasn't power. And according to the Christian Church, amassing personal wealth was close to a sin. Moneylenders (those who lent gold or other early forms of currency for interest) were considered sinful and often portrayed as despicable. Indeed, anyone making “money” by exploiting others (which is an important component of modern capitalism) would generally have been considered disreputable or evil, even if some people did secretly envy their comparative material wealth.

And ironically the Catholic church itself was one of the institutions that amassed significant material wealth back then, perhaps the biggest concentration of wealth apart from that of royalty.

The modern version of capitalism as a system for everyone owes much to European exploration, trade and colonialism (1500-1900). The Industrial Revolution (1750-1900) contributed to people changing from self-subsistence to wage labour, and a model of liberal democracy that arose in the 1600s, based largely around the concept of private property, began to trickle down to workers. The personal ownership of private property was not common in Europe before this period.

Modern Western capitalism really became a standard for most people in the 19th century as the Industrial Revolution led to many people leaving the work they had previously done on the land, in agriculture and raising animals for meat and dairy, to move to cities and begin working in factories for wages.

If you would like to read a more detailed look at the evolution of capitalism, I have provided the GNED reading "Capitalism: Where do we come from?" as an optional reading. This gives a more neutral account of the evolution of modern capitalism, while my lesson focuses more directly on a critical consideration of the downsides or limitations inherent in the system we all live by.

Some important critiques of Industrial Revolution-era capitalism

Though we are all probably aware of some of the most positive aspects of this economic system (greater social mobility, less poverty, lots of consumer choice), the system has been criticized from a number of perspectives over the years.

Traditional critiques of capitalism have often come from a social or social justice point of view or from philosophical/moral or even spiritual/religious perspectives. Critics insist that there is still too much distance between the haves and have-nots (that socio-economic class itself is unfair and divisive). Or they may point out that the emphasis on competition leads to selfish and non-cooperative attitudes in other parts of our lives, making human life ugly. They may regret the mechanization of human beings that happens in industrialization, and argue that too much of the work done under capitalism is dehumanizing and alienating. They may fear that a world Capitalist “religion” focused on wealth-accumulation and consumerism leads to inner emptiness and is not a noble calling for the human race. And so on. These concerns are deep ones about human rights, human dignity, and the meaningfulness of human life.

Critique 1: Karl Marx on Worker Alienation and The Division of Labour

In the 1800s there was increasing concern among philosophers and political thinkers about how capitalism was developing along with the Industrial Revolution. The most famous critic of capitalism, Karl Marx, focused attention on how working life had changed for most human beings under capitalism and industrialization. Work had became dehumanized, mechanized, competitive, and generally somewhat meaningless. Previously, most people's work had been focused on raising food or handcrafting goods. This was intrinsically meaningful work where the worker could feel involved and easily see the results of their labour; it was also generally cooperative work, engaged in with other human beings who were working for a well-understood common good (to eat, mainly).

With industrialization, instead of being focused on something of obvious importance that one was working on with others, like raising food, or something of a creative kind, like crafting a unique table, work tended to turn into a repetitious and mechanical process that one did in order to get money, which could then be spent on (supposedly) more meaningful things during the time one wasn't at work. Marx insisted that the modern worker was alienated from their labour, experiencing emotional detachment from what they spent the majority of their time each day doing. The system also sometimes encouraged them to become alienated from their fellow workers, feeling they were in competition with them, rather than cooperating toward a common goal.

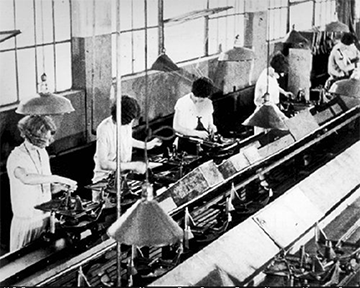

Marx criticized The Division of Labour, one of the foundations of Industrial Revolution-era capitalism. The Division of Labour refers to the practice of dividing up the activity of producing or processing goods into small micro-jobs that can be handled by workers who do not need to understand the whole process, and may not even know anything about the whole picture or the final outcome of their small part in the system. This practice came in with the industrialization and mechanization of processes of production. From the point of view of productivity and profit it made sense. By treating workers as small machine-like components in a process, labour could be less skilled (and consequently less well-paid), a worker causing problems could more easily be popped out of the workflow and replaced by another labourer, and workflows could work more efficiently.

The paradigm of this type of labour would be a worker who stands at a position on an assembly line and whose job, for instance, is to operate a punch on an endless stream of metal parts moving past him. The worker doesn't even necessarily need to know whether the part is for a tv set, a surgical drill, or a nuclear warhead. His or her job is simply to punch the metal.

In the Middle Ages, if you wanted a table, you would go to a skilled craftsman. That person might well create the entire table for you on his own, by hand. It might take some time and the table would be a unique artifact. Even in larger ateliers where several craftsmen worked on the tables, they knew and saw the full process of making the table, they might well know the person for whom they were making the table, and might eventually even see the look on the purchaser's face when he received the finished table. Their work had human meaning and showed traces a of personal touch, in other words: there was a social and interhuman dimension to it. The workers were not completely divorced from the beginning and end of the process of which they were a part. They understood the point of the work they were doing, and they were important to it.

Medieval woodworkers crafting furniture..

With the Division of Labour all this changed. A worker might stand on the assembly line all day, attaching one leg to an endless line of uniform tabletops going by. There was less reason for pride in one's work and less understanding of the full process: one was not fashioning a table but attaching legs. One was not making tables, one was making a wage. No one person made the mass-produced table; no single worker created a complete table on their own.

Marx considered this a serious diminishment in the meaning and value of work. In his notes, he draws specific attention to the dehumanizing effect of this mechanization: "With the division of labour the worker is depressed spiritually and physically to the condition of a machine" (Marx 1844). Marx recogized that the average human being spends the majority of their waking life working. Consequently, in Marx's view, it was crucial that the work be meaningful to the worker. Not that it be efficient or even lucrative, but that those precious hours of the worker's life would be spent doing something to which the worker was connected, for which they could feel some ownership and pride, and in which they had some say.

Marxist critics suggested that habits of mind nurtured by the Division of Labour led to a large majority of people who felt detached from what they did all day, and that this didn't just lead to people feeling unfulfilled and having no sense of ownership in what they produced. It also made people think of themselves as a tiny piece of a giant process they didn't really understand and had no control over. This made the average citizen feel no personal responsibility for the larger processes of society they were participating in, for good or evil.

Critique 2: Postcolonial criticisms and social equity concerns

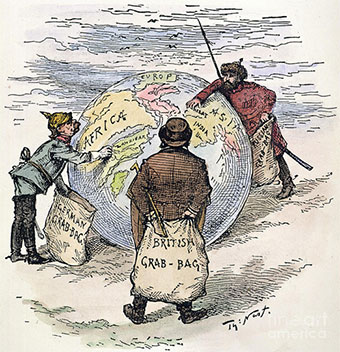

Historically, capitalism is now often seen as having been closely associated with European imperialist and patriarchal ideologies, and part of what fuelled its success was the European imperialist occupations and seizures of territories that belonged to non-capitalist or less capitalist cultures. As Marx and Engels had said in their famous Communist Manifesto of 1848, "The need of a constantly expanding market for its products chases the bourgeoisie over the whole surface of the globe. It must nestle everywhere, settle everywhere, establish connections everywhere." The "bourgeoisie" was their name for the new social elite that had emerged through capitalism: the owners of factories, the bankers, the people engaged in large-scale trade of consumer goods. These were the wealthy "owners," who didn't do the grunt work for the their wealth, but left that to the "common people" or the "natives." The leaders of this new class were of course men, and predominantly white men.

Germany, Great Britain, and Russia dividing up parts of Africa and Asia in one of the many anti-imperialist cartoons from the 1700s and 1800s.

Capitalism has thus been criticized as an arm of white supremacism and Western imperialism. Historically, and to some extent still, capitalism has often relied upon or encouraged various forms of inhuman and exploitative activity, including human slavery, colonial control of indigenous populations, and cultural imperialism (see week 5 lesson if the last two terms now seem unfamiliar). Often capitalist enterprises could not have been so successful without the exploitation of non-whites.

For instance, the successful economic model of plantation agriculture practiced in the Southern United States in the 1700s and 1800s depended for its viability on the large force of enslaved labourers who had been imported from Africa to do unpaid work. When slavery was abolished at the end of the American Civil War (1865), the Southern economy collapsed from the combined devastation of the war costs and the loss of its slave labour force. Much of the south has never really recovered economically.

Throughout the 1800s, the capitalist strategies of growth, exploitation of resources and markets, and industrialization and automation entailed a nightmare of human rights violations: appropriation of indigenous lands, aggressive imperialism and racist oppression, and even - as just mentioned - outright slavery, most notably in the United States and Brazil. Much of this inhuman activity led to profits primarily for those running the new Euro-American exploitation of the planet.

Women may also have been disadvantaged in the rise of capitalism. As deprivileged as women were in the Western world before modern "civilization," there were certain ways in which their position became worse with that other "division of labour" that became common throughout the 19th and 20th centuries: men at work and women at home. In 1981, Angela Davis published a groundbreaking critical history of Women, Race and Class. In a fascinating chapter on the history of housework, she discussed the scandalous gradual degradation of women's labour into unpaid housework and drew attention to the fact - already pointed out in the 19th century by Karl Marx's collaborator Engels - that women's status had actually continued to go down after the Renaissance, with the development of industrialization coupled with capitalism:

As Frederick Engels argued in his classic work on the Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State [1884], sexual inequality as we know it today did not exist before the advent of private property. During early eras of human history the sexual division of labour within the system of economic production was complementary as opposed to hierarchical. In societies where men may have been responsible for hunting wild animals and women, in turn, for gathering wild vegetables and fruits, both sexes performed economic tasks that were equally essential to their community’s survival. Because the community, during those eras, was essentially an extended family, women’s central role in domestic affairs meant that they were accordingly valued and respected members of the community. (Davis 1981)

Many women worked alongside men in the mechanized factories of the 19th century, but as general wealth increased, ironically women began to lose status and became unpaid home workers relying on men for support. By 1950, this was the model in America, and people tended to think it had been like that forever. On the whole it is probably fair to say that as things "improved" for the average white man under capitalism+mechanization (more social mobility, more personal wealth) , most other people were likely to lose status or freedom as part of the cost.

Some of the problems with these white-dominant and patriarchal imperialistic movements are still present in different ways in contemporary globalization, which has been a major component of the "neoliberal" version of capitalism (see below). Many would say that something dangerously close to slavery happens in many developing countries: sweatshop labour, where countless people spend long hours on hard meaningless tasks that are generally poorly remunerated, often in unsafe conditions, but where they have few alternatives.

The neoliberal version of capitalism

Conservative British prime minister Margaret Thatcher popularized the slogan "There is no alternative" to affirm that capitalism was the only viable economic system. This seemed to be confirmed when the "communist" former Soviet Union collapsed in the late 80s.

In the second half of the 20th century the neoliberal version of capitalism became what most people in power in North America considered the norm, and was embraced by movers and shakers in other parts of the world as well. According to this version, capitalism should become the economic system of the whole planet - it will bring freedom, fairness, and prosperity with it. Globalization and free trade are good; everyone profits. The United States - the richest country in the world - is the model, the ideal. Every country in the world should try to follow the example of the United States: industrialization, wage labour, and trade across international borders. National governments should avoid regulating the marketplace; free trade on a global scale will lead to everyone enjoying the standard of living that people have in the United States, and similarly developed countries like Canada and most of Europe.

In the 1980s, three of the basic foundations of this neoliberal capitalist model were established: globalization (global free trade will profit everyone), "there is no alternative" (the idea that capitalism is the only viable economic system for human beings), and trickle-down economics (the idea that as the rich get richer, the wealth will naturally trickle down to everyone else as well).

The promise of capitalism seemed to be that every human being would eventually be able to live as well as the typical middle class American of the 1960s. That means they would have lots of private property, and could consume an endless range of products, and that everyone would just get richer as long as there was continued economic growth.

When I was a kid in California in the 1960s, this seemed perfectly plausible. Americans had never been more prosperous, especially middle class white Americans. My family was barely middle class, but we had a house, two cars, two tv sets and lots of new plastic toys at Christmas. It did indeed seem like things would just keep getting better.

Critique 3: Problems with globalization

A serious part of the neoliberal system as it has played out in North America has been the "offshoring" of various kinds of labour to the developing world. On the one hand, this has meant cheaper labour costs for manufacturing and processing of goods, and this has kept the prices of consumer goods in North America down. But it comes with two kinds of human cost.

Workers in developing countries can be paid less than workers in North America and still enjoy better lifestyles than if they remained subsistence farmers in the countryside. But pay is low and working conditions are often gruelling and unsafe, and the work itself is often meaningless and alienated in the way Marx suggested. Most developing countries have less strict safety and health standards for workers than we have in Canada, and many of the people who produce our consumer goods are still living in what we would consider poverty. Think of the coffee growers with whom Aileen Herman lived, as discussed in her Politics reading.

Situations like the collapse of the sweatshop complex Rana Plaza in Bangladesh in 2013 are well known. This was a giant building that housed a number of clothing factories, producing clothes for – among others – Joe Fresh, Benetton, and Walmart. Though cracks had been noticed in the structure, there were not enough safety regulations in place, and it was left to collapse one day, killing 1130 people and leaving 2500 injured.

Because so many major companies have become multinationals, we have a situation now where a company headquartered in Canada can outsource various parts of the production process to parts of the world where labour is cheaper, usually partly because they don't have the workers rights legislation in place that we have in Canada. This makes you and I - whether we know it or not - complicit in sweatshop labour abroad, whose products we enjoy at more affordable prices without generally having to think about where they come from.

Foxconn dorms rendered suicide-proof by barring the windows.

The situation at the Foxconn industrial park in China in 2012 is often used to dramatize the plight of the overseas workers who produce our products. Foxconn workers were involved in the manufacture of BlackBerry, iPhones, PlayStation, Xbox, Kindle, Wii, and similar devices. The workers lived in dorms on site. They worked long hours doing often meticulous and stressful work, and then went back to their dorms for a meal, a couple of hours of tv, and sleep, to do it all again the next day. In 2010, following 14 suicide-related deaths, a report that involved research by universities in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China described Foxconn factories as "labour camps" with widespread worker abuse. In 2012, 150 workers threatened to commit mass suicide to protest their working conditions. The workers were threatening to jump from the upper stories of their dorms. Rather than addressing their suffering, Foxconn's initial response was to install nets below, so that workers would not die if they jumped, or to put bars on the windows, so that they could not get out of the dorms to jump.

The complicity in worker suffering abroad is not the only problem that globalization has presented to Canadians. Part of the neoliberal rationale was that there would be a "trickle-down" effect in economics: as the rich got richer, the wealth would trickle down to enrich the rest of us as well.But in order to keep labour costs low, a lot of jobs that would have traditionally been available for Canadians have been offshored to developing countries. Many of the Canadian manufacturing jobs were unionized and well-paid with good benefits, and have now disappeared. Our consumer goods have remained cheap, even gotten cheaper, but our middle class has meanwhile also been shrinking for the last 40 years or so, and there seems to be a growing distance between the rich and the rest of us. The trickle-down effect has not apparently led to a growth in the middle and upper-middle class in North America. So critics argue that the wealth did not in fact trickle down - at least not to North Americans.

Critique 4: Shrinking need for human labour

Even if the criticisms I've looked at so far seem serious, one could hope the they are not part of the capitalist economic system inevitably, but problems that have arisen when people have pursued profit too single-mindedly at the expense of all other (humanitarian or moral) values. But now we're going to take a quick look at two more recent concerns about the sustainability of the capitalist model in the 21st century. These seem to be serious problems that capitalist proponents will have to face if the system is to remain or become something good for a majority of humanity.

A new 21st century concern people now have is whether the capitalist model will still work for the benefit of the majority with the advances in technology that are happening right now. With the growth in Artificlal Intelligence (AI) and robots, an already large "useless class" of people could become the majority of us, and traditional Industrial- and Post-Industrial-era jobs may not be available for most people. Automation and mechanization will extend beyond the check-out counter, into factories, distribution centres, transportation, and even care-giving centres like hospitals, schools, restaurants, and other traditional workplaces. There will be no need for human employees when AI, robots, and automated systems can do most of what humans do now for their jobs.

How will we support ourselves or who will support us if there are no jobs for most of us? We don't know right now. The influential historian and futurist Yuval Noah Harari, in 21 Lessons for the 21st Century, speculates that with the rise of Artificial Intelligence and robots, the mass of workers are destined to go from exploited to irrelevant, without any intermediary period in which all 8 billion of us have interesting creative jobs. Maybe we should be happy that robots can't quite yet act as priests, psychoanalysts, nurses, teachers, or even call centre staff. Once the machines can care better than we can, it's hard to see what labour any of us will be able to exchange for wages.

Wage labour is one of the building-blocks of capitalism, and one of the things that supposedly make it good for "the people." If there are fewer and fewer jobs that it makes sense to pay humans wages for, how can the model continue to operate? What will happen to us as our work becomes unnecessary for production and distribution - when robots build products, drones deliver them, and AI's provide our health care? Will we have to provide "entertainment" for the wealthy and hope they throw us some scraps? Will the government force redistribution of wealth and pay everyone a monthly salary just for existing? How will the model adapt to the vastly decreased need for wage labour that continued technological advances seem to be bringing?

Critique 5: Ecological Unsustainability

And, finally, we now have one more clear challenge to the capitalist model: the realities of our natural environment itself. This may be the thing that forces capitalism to evolve or die, or that forces us to invent a new system for the distribution of goods and services. This is the subject of the reading for week 12 coming up, so I will largely leave it aside for now. But the basic idea is this: neoliberal capitalism assumes that everyone's wealth will eventually increase as long as there is unhindered economic growth. But that is not feasible on a planet with a closed ecosystem, and as people get wealthier they in fact have so far led to more destruction and degradation of the natural environment. The capitalist model is unrealistic as a system operating in the physical reality of our natural world, at least with a population of 8 billion human beings, all hoping to work and consume on the American model.

Human values other than "dollar value"

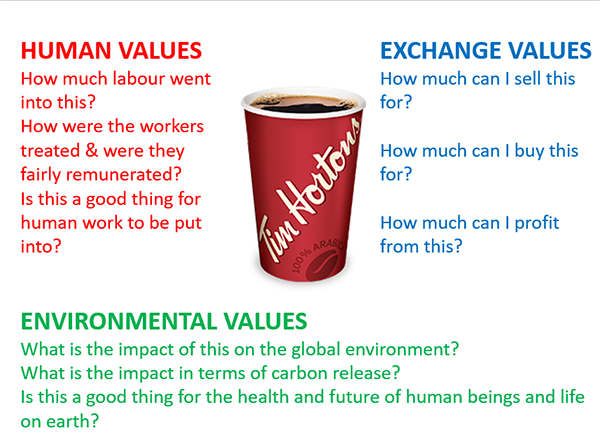

Both humanist (and also religious) and environmental critiques of capitalism suggest that the economic model is too focused on abstract exchange value, endless growth, and financial profit while ignoring other aspects of reality and life, human and otherwise. Many values apart from monetary value are part of human life and of reality itself that are generally ignored by capitalist economics. The economic model is focused on exchange values; humanist critiques of capitalism (and defenses of it) are focused on human values; and the environmentalist critique is focused on environmental values.

Think back to the cup of coffee that Aileen Herman talked about in the reading on Politics. It can be analysed from many value perspectives, not just the perspective of the market.

The reading by Suzuki and Moola that we will look at during Week 12's lesson suggests that the economic model on which capitalism is founded is not realistic about the actual circumstances of nature as a closed and fragile system on planet Earth. As capitalism spreads and advances, the resources of the planet diminish and the ecosystem is threatened with collapse from the climate change and pollution that capitalism has indirectly fuelled, no pun intended.

FOR TESTING

- Capitalism and the briefly outlined development of it

- The Marxist critique of capitalism: Alienated Labour

- The Division of Labour and why Marx thought it was evil

- Postcolonial and social equity critiques of capitalism

- Neoliberal assumptions about capitalism

- The problems raised by neoliberal globalization

- The concern about the future of wage labour in a world of Artificial Intelligence and robots