CULTURE AND Nature

Be sure you understand

- The origin and meaning of “all my relations” and how this attitude might relate to the Climate Crisis.

- What the David Suzuki Foundation says is the single most important step an individual can take to fight climate change.

- Mitigation strategies currently on the table

- Ways you can personally work to combat climate change

- Why eating less meat would be a good thing (the whole story – overpopulation, methane, carbon release in production and transportation, normalization)

- The meaning of normalization and its possible relevance to personal action against the climate crisis.

BACKGROUND TERMS

GREENHOUSE GASES

Gases that trap heat in the atmosphere. There are several different types of greenhouse gases, but two in particular are responsible for climate change: carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4).

FOSSIL FUELS

Coal, Oil, Natural Gas. Fossil fuels include coal, petroleum, natural gas, oil shales, bitumens, tar sands, and heavy oils. All contain carbon and were formed as a result of geologic processes acting on the remains of organic matter.

CARBON SINKS

A carbon sink is any natural or technological process that absorbs carbon from the atmosphere. Trees, soils and oceans are the most important natural carbon sinks, but all three are limited in the amount of carbon they are capable of absorbing.

This lesson talks about the climate crisis. The official Canadian Encyclopedia reading can tell you more about the current scientfic understanding of the crisis. This lesson comes at the topic from a slightly different angle: how some of the dominant human cultures relate to the realities of nature.

Reality bubbles

Nature is one of the most fundamental forces that shape our world. But it is very easy for us to lose sight of this. If you ask a typical Canadian what forces shape their world, they will likely start with economics and technology, and then may mention politics, or - if they are being a bit more critical in their thinking - maybe racism, privilege, or some other human ideological power-structure. Living in cities, focusing on jobs and school, interacting with other human beings and pets but with few other living things directly, and spending so much time consuming unreal images from technology, we are inclined to forget that we're part of nature.

If you would like to disrupt this blindness, I can recommend an entertaining and eye-opening book by science broadcaster Ziya Tong, The Reality Bubble (2019). Tong's book is a science-based onslaught on how delusional many of our ways of perceiving reality have become. Those of us in the developed world live in cities; our food comes to us packaged and processed, our garbage magically disappears once a week, our shit goes down the drain and we never have to think about it again. And of course, we spend a huge amount of our attention on distracting entertainment media and the seemingly inescapable work and economy that our technology has created for us and that our institutions - including Humber College - largely insist are the central focus of human existence.

But in fact - and the pandemic has helped some of us to grasp this - we are animals: vulnerable, mortal, physical - desperately dependent on the rest of life on earth, on the oceans, on the weather and the oxygen we breathe, on fresh water, on microorganisms within us and in the environment that even scientists don't fully understand - and all this is mostly hidden from us by the lives we have chosen to lead (perhaps we have chosen this way of living so we can avoid as much as possible the reality of what we actually are). The COVID-19 pandemic has been a wake-up call about some of this. Our lives are at risk not because we don't have a good enough paying job but because we're animals, and an invisible microorganism can change everything. In an effort to avoid the loss of human life and the collapse of our man-made health care systems, the economy can be drastically slowed down and we are forced to change our way of living because of this nasty little bug. I think there's a valuable lesson here about the basics of life, which privilged people in the wealthy nations of the world have largely been able to lose touch with.

Before the coronavirus and continuing alongside it we have the climate crisis. Most people are now vaguely aware that this poses a huge threat to our way of life, if not to our whole species and certainly other forms of life on earth. But the reality of the threat is very low for most of us, compared to the threat of FOMO or our chosen career being taken over by AI and robots.

Most of us know next to nothing about science; but science is a tool that allows us to see more of reality - non-human reality - than we can see with our eyes. If you recall Plato's original interpretation of his allegory it was that what we can know with our five senses are shadows of a fuller reality. The Enlightenment interpretation of the allegory said that science and rational thought were what could take us out of the cave of shadows. Most people have not bothered to go there.

We are not machines or computers; we are part of life, animals that are intimately connected to the rest of life on earth in a network of interdependent relationships.

European settler attitudes to nature

The culture we have inherited in North America comes from the white colonists who slowly pushed out and suppressed the people who were living here when they arrived: the indigenous people's of Turtle Island (one common indigenous way of referring to what the settlers called America).

The white Europeans were largely committed to a culture that revolved around "the three C's" of settler midset: colonization (settling and taking over land), Christianity (the "true" religion that should be shared with/enforced upon anyone who didn't have it), and commerce (Capitalism). The settler attitude to land and natural resources was to see them as resources to be exploited for capitalist gain and personal wealth. They believed in the private ownership of land (an attitude most indigenous people didn't understand or agree with), and that the land and non-human life were there to be exploited for profit (again, a very different attitude from how indigenous people saw their relationship to the rest of life).

Though colonization may now be complete and Christianity may have faded as a universal ideal, the attitudes of Capitalism toward the rest of life, the land, and the environment have persisted. We tend to see nature as something separate from us, and of which we are or should be "the boss." This is quite a central aspect of the invented human culture of Capitalism, and one that some people say is largely responsible for the risks we are at now from climate change.

All my relations

The invented human cultures of the indigenous peoples of Turtle Island tended to have a quite different attitude toward the relationship of human beings to the rest of nature. The Lakota people have a saying that has been adopted by many North American indigenous groups: "All our relations." This saying -sometimes a prayer, sometimes a greeting, sometimes a motto - acknowledges our deep connection to the rest of life and the fact that humans are really just one small part of life. Most of us city-dwellers in the Western world are almost wholly detached from that reality in our day to day existence. With our settler capitalist culture, we may see ourselves not as one form of life among many, but as human beings, separate from and above the rest of nature.

All my relations is a powerful counter-culture that is worth exploring. For one thing, it is closer to the reality-based culture of Western science than the capitalist attitude toward nature is. For another, it is arguably a more wholesome attitude to have toward the world we live in.

As the late Richard Wagamese wrote, this cultural attitude isn't just about the fact that you are related to your family or other people who you feel are part of your subculture. "Not just those people who look like you, talk like you, act like you, sing, dance, celebrate, worship or pray like you. Everyone. You also mean everything that relies on air, water, sunlight and the power of the Earth and the universe itself for sustenance and perpetuation. It's recognition of the fact that we are all one body moving through time and space together." ("'All my relations' about respect," Kamloops Daily News, June 11, 2013)

At a 2024 conference on environmentalism, 93-year-old Haudenosaune elder Oren Lyons made the point even more powerfully, perhaps. He said that in traditional indigenous cultures, people didn't see humans and special and the rest of nature as "wild." Rather they looked on nature, with themselves in it, as "a community." Imagine how our treatment of the enviroment might change if we all saw ourselves as a part of its "community."

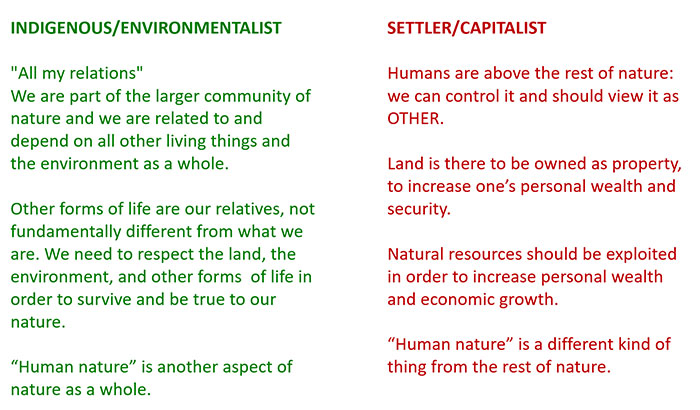

Two imaginary ways of conceiving humans beings and our relationship to the rest of nature

To summarize quickly the large incompatibility of the indigenous and settler ways of seeing reality, we could consider this table:

If we think of "reality" as something separate from human culture and not under our control, which of these ways of looking at our relationship to nature seems more "reality-based" to you

Our lack of attachment to the culture of science

If you would like to understand the background science a little better, you can start with the Canadian Encyclopedia article on Climate Change that is this week's reading, or if you don't have that much time you could at least watch this 4-minute video by popular science broadcaster Neil deGrasse Tyson.

In terms of this lesson, the most important point he makes is at the end: we can't SEE carbon dioxide. If we could actually see the CO2 we are releasing to the atmosphere, it might help us take the problem seriously. But our senses don't allow us to see, and without a much more solid grounding in science, it's hard for most of us to treat greenhouses gases a real.

Similarly, we have very little understanding of the connectedness of lifeforms, including at a microscopic level. So if we think of climate change as mainly ourselves having to deal with more extreme weather or hotter temperatures we are ignoring the hidden dangers than science could help us see. If we hear that some beetle, coral reef organism, or microbe in the soil may become extinct because of climate change, we may care little about this organism. But the organism is actually part of a great chain of interdepencies in the natural world. Its death may lead to other species not being able to survive, and a chain-reaction that could prove devastating for species we actually care about, such as coffee plants, chickens, or the trees that help keep us from all burning up.

What's wrong with global warming?

With the harsh Canadian Winters, global warming can sound like a positive thing. But it is as certain as science can be that if temperatures warm globally the way scientists are anticipating they will if we don't make changes, then the delicate balance of life on earth will eventually be catastrophically impacted. Scientists speculate (and already have some good evidence) that warming will lead to an ecological "domino effect" that makes parts of the world uninhabitable, destroys agricultural environments we currently rely on for food, drowns out coastal cities, entirely submerges small island countries, devastates animal and plant species, and throws us into an ecological crisis in which many human beings will suffer and die. (Leaving aside the suffering of all our non-human relations.)

If you wonder how you, living here in Ontario, will be affected, the answers are speculative but certainly still frightening. Assuming no radical action is taken and that you are still living in Ontario in 2050 much will likely have changed (in all things, obviously, but also in terms of the natural world, unless we slow or stop our greenhouse gas emissions). Ontario taken in isolation may be able to prosper from global warming. Our winters will be warmer, more of the land up north will be able to be farmed or inhabited by Canadians, etc. In terms of survival, if the Ontario of 2050 is similar to the Ontario of today only warmer, then Ontarians should be able to feed themselves and generate energy and enjoy the beach for longer. Assuming the rest of the world stayed the same as it is now and only Ontario warmed up, that is.

But Ontario is not an isolated island in the world. Other parts of the world could be finding agriculture impossible. Many people there will be struggling or dying. Many of the foods and other goods we are used to enjoying in Ontario may become unavailable, or too expensive for any but the wealthiest citizens. We must hope that our national borders are still respected, but I wouldn't count on that. Huge populations from countries around the equator where it is no longer possible to grow food will be streaming northward, looking for asylum. They will probably be desperate enough to by-pass legal immigration systems. A major military power may decide to invade Canada to get our relatively liveable land and still comparatively plentiful natural resources. We have a lot of water, a lot of farmable land, a lot of forests, fossil fuel reserves, and a comparatively small human population. We may not be able to maintain our soverignty in the face of critical problems like famine elsewhere in the world. Much of the world will probably be suffering and hungry. Some of it is heavily armed, and civilzed diplomacy seems to be increasingly dispensed with.

And of course, if one cares at all about those other human beings who aren't Ontarians, and other species who aren't human beings, then the results may seem ugly and wrong even if they don't affect us comparatively lucky Ontarians as much as they do others.

These scenarios are all speculation, a kind of science fiction really. But it is science fiction based in science fact and on the best guesses and computer projections that very smart people have been able to come up with. Environmentalists are still hopeful that humanity can be proactive, and fight against this potential crisis before it happens, rather than waiting until the eco system we have known for most of human history collapses and we decide that we have to do something because we are starving and dying, and killing each other for habitable land and food.

3 ways global warming can be slowed or stopped (plus one way in the future, maybe)

I am now going to discuss what we can do about this imminent danger if we choose to recognize it. (If you don't believe it's important, you can just use this as another exercise in understanding how other people think and thinking about it critically yourself.)

There are four serious strategies humans have thought up so far for dealing with this "climate emergency." Three of them are things we can begin doing right now, the fourth is more of a dream for the more distant future. Debra Davidson in the Canadian Encyclopedia article talks about these as "mitigation strategies" - ways the damage can be mitigated (made less severe or destructive).

1. Reducing our greenhouse gas emissions

This is the traditional solution, and the one we are already in a position to implement, though it will be hard and costly and really requires global cooperation that the world is not prepared for right now. The basic idea is this: we will use less energy, consume less. and switch as rapidly as possible to using energy that involves little to no carbon emissions. This is something individuals can do in smaller ways that would add up (drive less, consume less) and that governments and corporations will need to make happen (no more fossil fuel burning; reduced packaging and transportation, etc).

2. Carbon capture

The idea of this approach is that everywhere that carbon is released (cars, factories, etc) we install technology that captures the carbon and then we bury it, like other waste, so that it never gets into the atmosphere. The focus here is particularly on our power plants, many or most of which currently burn fossil fuels to generate our electricity. The carbon capture approach is being tried in some power plants, including one in Saskatechewan. The problem with it is that the method is expensive, and most governments (and voters) are still reluctant to commit the massive resources necessary to make it happen on a large scale. In some other major fossil fuel-burning countries it is not even being explored yet.

3. Reabsorption strategies

Forests, plants in general, and the planet's oceans naturally absorb carbon from the atmosphere. Thus, reforestation is an important step that can be taken to keep natural "carbon sinks" in place. On the other hand, something like the burning Amazonian rainforests are both actively creating carbon and destroying natural carbon absorbers. Hence the concern about that situation. There is some exploration into creating artifical carbon-absorption processes through technology, but these are probably still far in the future. In the meantime, planting trees and other carbon absorbing plants is a good step everyone can take, and that governments may explore on a more extensive level. In Toronto, home owners have long been obliged to let the municipal government plant trees on their property in order to add to oxygen production and carbon absorption in the city. This is one of the few cases where I find the government forces us to do stuff we might not want to do, but I am personally in favour of what they are forcing us to do. (They wrecked my front garden taking out a dead tree and then planting a new one months later, but I don't mind the way it is growing now.)

4. Geo-engineering (not a real option at this time)

In addition to those three strategies, which could be implemented now if enough of us demanded it and were willing to make some sacrifices, there is hope that in the future technology will give us forms of geo-engineering that will allow us artificially to create massive environmental changes through technology that would lower the carbon in the atmosphere or lower temperatures in some other way. Such techniques are still merely speculative, and like all human technological advances there are risks of unintended negative impacts that might be felt on the global scale. We'll return to such concerns about the impossibility of predicting consequences of technology in the lesson on biotechnology in week 13.

We can voluntarily reduce our carbon impact today by significantly cutting back our individual consumption and changing our lifestyles (see below); as well and - more importantly - if we believe in the science and want to be proactive we need to influence our governmental policy-makers to make this a top priority, enforce carbon emissions reductions on manufacturing and other large-scale industries, and start converting to non-fossil-fuel sources of energy immediately.

Who is responsible for the climate crisis?

This is a question that can be answered in a number of ways. All of us consumers are contributing to it, especially if we drive cars. The country that seems to be most drastically releasing CO2 and shows no sign of decreasing is China. India and other nations in the developing world are not part of UN efforts to curtail carbon release and do not typically have environmental protections as strong as those in Europe and North America.

Canada is only responsible for at most 2% of carbon emissions. Nevertheless, we are more of a problem than some countries because it is so cold here. We may have the highest per capita carbon footprints of any nationality. Another aspect of Canada that makes it play a bigger part than you might think is that we are one of the countries with the largest desposits of fossil fuels, and our decisions about whether to continue extracting them or not may influence other countries' readiness to make the painful move away from fossil fuels.

Corporations involved in manufacturing and distributing goods are a huge force in carbon release. If we did not have globalized supply chains and economic growth throughout the developing world, the carbon impact would be much less.

We can try to blame "the Billionaires" - and certainly they are blameworthy - but you and I as consumers are, ultimately, the reason for much carbon release in the world today.

What can you personally do about climate change

Assuming you believe that climate change is real, that it is caused by humans, and that it is dangerous for our future (and much of the other life on the planet) do you have any sense of what you personally could do if you wanted to fight against it?

When we've polled students in the past, the number one answer is often recycling. Unfortunately, recycling in its present state - though it is a good idea for other reasons - will do little to combat climate change. There are many other things we can do that are more likely to have a larger impact.

The Canadian broadcaster and environmentalist David Suzuki has a foundation whose web site discusses a number of actions worth taking. They can be broadly divided into political action and lifestyle/culture changes.

According to the David Suzuki Foundation, the number one thing an ordinary Canadian citizen can do to fight climate change is to engage in political action. If you care about making the climate safer, you should be voting for parties that prioritize this issue. Political action could also involve signing petitions, taking part in public demonstrations, writing to your members of parliament, and sharing information about such activity on your social media.

Lifestyle changes

Lifestyle changes involve things like driving less, consuming less, reusing things, repairing things, and eating less meat. Some of these are discussed in more detail below. A single individual's lifestyle changes may have little impact by itself, but combined with millions of other single individuals changing, they will. An important aspect of changing your lifestyle is normalizing these lifestyle changes. The more people who shop thrift stores instead of fast fashion, the more people who go vegan, the more people who ride bikes, the more normal and "right" these activities will seem to others, and the more it becomes the standard for our society, instead of a seemingly crackpot fringe.

It is no exaggeration to say that our hyperconsumption habits in the "First World" and the ever-increasing manufacture of unnessary consumer goods in the developing world are major contributors to the current emergency. Most of our consumer goods in the contemporary world involve terrible impacts on carbon levels. Natural resources are destroyed; manufactuing burns coal or uses power that comes from carbon-releasing sources; we transport the products over incredible distances (all the way from China to Canada, for example); and the products are generally over-packaged in non-biodegradable plastic or paper that should either be composted or recycled but often aren't. The next time you buy a bag of candies, in which each candy has been individually wrapped in plastic, think about how much processing had to go into it and how much waste is involved - for what is also probably an unhealthy and unnecessary consumer product. (Does it even really taste all that great?) It may be good for the economy, but it is terrible for the ecology.

When you do want or need something, consider buying second hand, upcycling, making things yourself, repurposing something you already have, fixing something that is broken, sharing ownership and cost with someone else. All of these can actually be quite satisfying and are more creative and compassionate than endless selfish consuming of new junk. You will also save money. Fast fashion is out; thrift hauls are in.

Thus, one of the 10 best things you can do on the list provided by David Suzuki's web site is Consume less. Of course, we have little else but consumption to bring meaning to our lives in the Western world, and we have been told that our consumption is necessary for the economy and that everyone will get richer the more we consume. This may be partly true for a time in a limited economic model, but, as we'll see in a couple of weeks, David Suzuki insists that it is no longer a sustainable model for our species.

Eat differently

A chicken-processiong and -packaging plant in China. Sometimes chickens are shipped from Canada to China for cheaper processing and then shipped back to Canada or to other parts of the world.

The factory production of meat and dairy has a huge impact on greenhouse gas emissions. Cattle produce enormous amounts of methane; forests are destroyed to create grazing land, removing natural carbon sinks (forests absorb CO2 from the atmosphere and thus reduce the greenhouse effect); and meat and dairy are processed and transported large distances in ways that add to the carbon footprint.

I am going to spend a little more time here on the "cheap meat" industry because it strikes me as a very clear example of humanity out of control - but in a way that is conveniently out of sight from the average citizen. In the book The Reality Bubble that I mentioned above, Ziya Tong takes the reader through a dizzying and nauseating survey of how the meat industry works so that everyone in a wealthy country like Canada can have cheap meat at every meal if they want to. I'll leave it to you to decide whether you want to know about the horrors that the animals endure - most of us would rather not know - but even just the scale at which meat production happens worldwide is monstrous:

Today, there are over one billion domesticated pigs on Earth, one and a half billion domesticated cows, and, according to annual slaughter numbers by the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, almost sixty-six billion chickens. What this means, as George Musser, an editor at Scientific American, put it, is that “almost every vertebrate animal on earth is either a human or a farm animal.” Including horses, sheep, goats, and our pets, 65 percent of Earth’s biomass is domestic animals, 32 percent is human beings, and only 3 percent is animals living in the wild. (Tong 2019)

In other words, most of the animal weight on earth at present (97%) is human beings and the animals we have domesticated, mainly in order to eat them! This is one example of how radically humans have changed nature and diminished biodiversity.

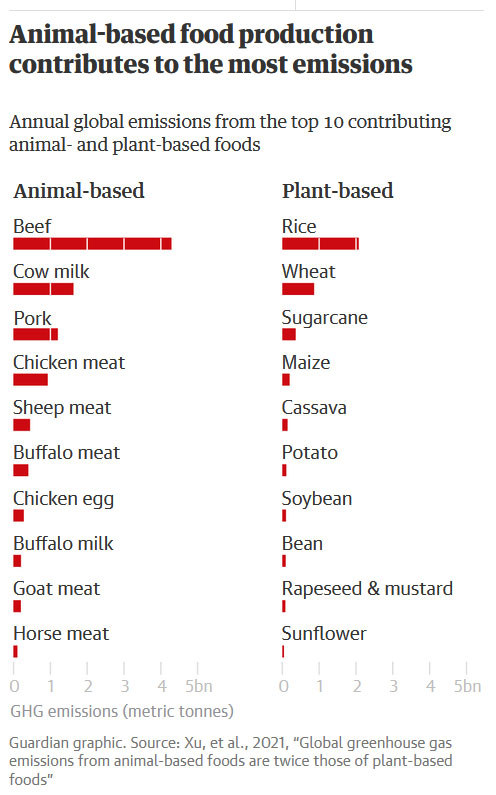

Source: Oliver Milman, "Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds," The Guardian Mon 13 Sep 2021.

A 2021 study publicized in The Guardian indicated that meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production. Cattle release huge amounts of the greenhouse gas methane in their burps and farts, and the factories and transportation that make make meat comparatively cheap are large contributors to carbon release.

The entire system of food production, such as the use of farming machinery, spraying of fertilizer and transportation of products, causes 17.3bn metric tonnes of greenhouse gases a year, according to the research. This enormous release of gases that fuel the climate crisis is more than double the entire emissions of the US and represents 35% of all global emissions, researchers said.

“The emissions are at the higher end of what we expected, it was a little bit of a surprise,” said Atul Jain, a climate scientist at the University of Illinois and co-author of the paper, published in Nature Food. “This study shows the entire cycle of the food production system, and policymakers may want to use the results to think about how to control greenhouse gas emissions.”

The raising and culling of animals for food is far worse for the climate than growing and processing fruits and vegetables for people to eat, the research found, confirming previous findings on the outsized impact that meat production, particularly beef, has on the environment. (Oliver Milman, "Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds," The Guardian Mon 13 Sep 2021)

The desire to provide everyone on the planet with a steady diet of meat protein has led to grisly overexploitation of animals and a mammoth impact on the levels of greenhouse gasses. We now find both environmentalists and animal rights activists encouraging everyone to reduce our meat consumption, avoid "cheap meat" (processed and/or mass marketed meat, such as is used in fast food, frozen and canned food, and generally in supermarket meat) and cheap dairy (which is also an industry full of cruelty with a significant impact on carbon levels). The ideal, according to environmentalists, would be for us to embrace veganism, or hugely reduce our dairy consumption and eat meat at most once or twice a week.

- Eat less meat and dairy; go vegan when possible

- If you do eat meat or dairy, buy local, organic, naturally raised products whenever possible

- Don’t waste food; consume more carefully

- Grow your own (I've done it; it's fun and really makes you appreciate what goes into the food we eat)

So, some things an individual can do: vote for climate action, spread the word, consume less, eat less cheap meat.

Normalization

The things individuals can do on their own or in small local groups are not completely insignificant, but they would probably never be enough to halt the crisis, unless everyone got on board with them.

However, to begin practicing these things (less consumerism, eating less meet, driving less) can also be important because it shows other people that these things can be done and are not even necessarily negative experiences. Thus, living more sustainably begins to become common in society and seems more normal.

Normalization is the cultural process through which new social norms evolve and become established. Norms change, and we can help them change. For instance, when I was a child in the 1960s, there was a huge number of people who smoked cigarettes. Smoking was considered "cool" by many people, cigarettes were advertised on television, and rarely would anyone even complain about second hand smoke.

Over the course of my life time, though, the norms around smoking evolved. Nowadays, comparatively few people still smoke cigarettes in Canada, people take seriously the health hazards of smoking and second-hand smoke, and the the government has restricted advertising of tobacco and made smoking look unappealing through packaging. People who smoke nowadays are often ashamed of it, try to hide it, sneak out, and avoid bringing second-hand smoke into the environments where other people could be affected by it (or even aware of it). In other words, the norms around smoking changed. Partly through the efforts of ordinary people and partly through more education and public messaging about the dangers of smoking.

The same thing could be done with things like hyperconsumption, over-consumption of cheap meat, driving gas-burning cars, and so on. These things could begin to seem yucky, and the norms could be changed, partly through some people adopting new norms around those things and showing people the way.