The Society of the Spectacle

Be sure you understand

- The society of the spectacle (Guy Debord and the Situationists)

The phrase Society of the Spectacle draws attention to the way modern people in developed countries have gradually become passive spectators of media (eg watching tv, scrolling through TikTok) rather than doing things themselves in the real world. - Worries about television replacing reading and the effect on democratic citizens (Neil Postman)

Broadcast mass media

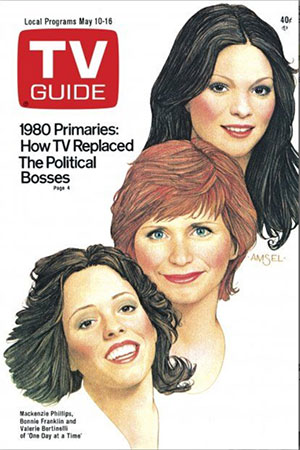

- Replaces complex ideas with simplified images

- Replaces positions with personalities

- Replaces arguments with ads

- Replaces active understanding with passive entertainment

- Is escapist, distracting, often fake, exploitative

People are encouraged by this type of media to become passive consumers, and treat real things as unreal and unreal things as real

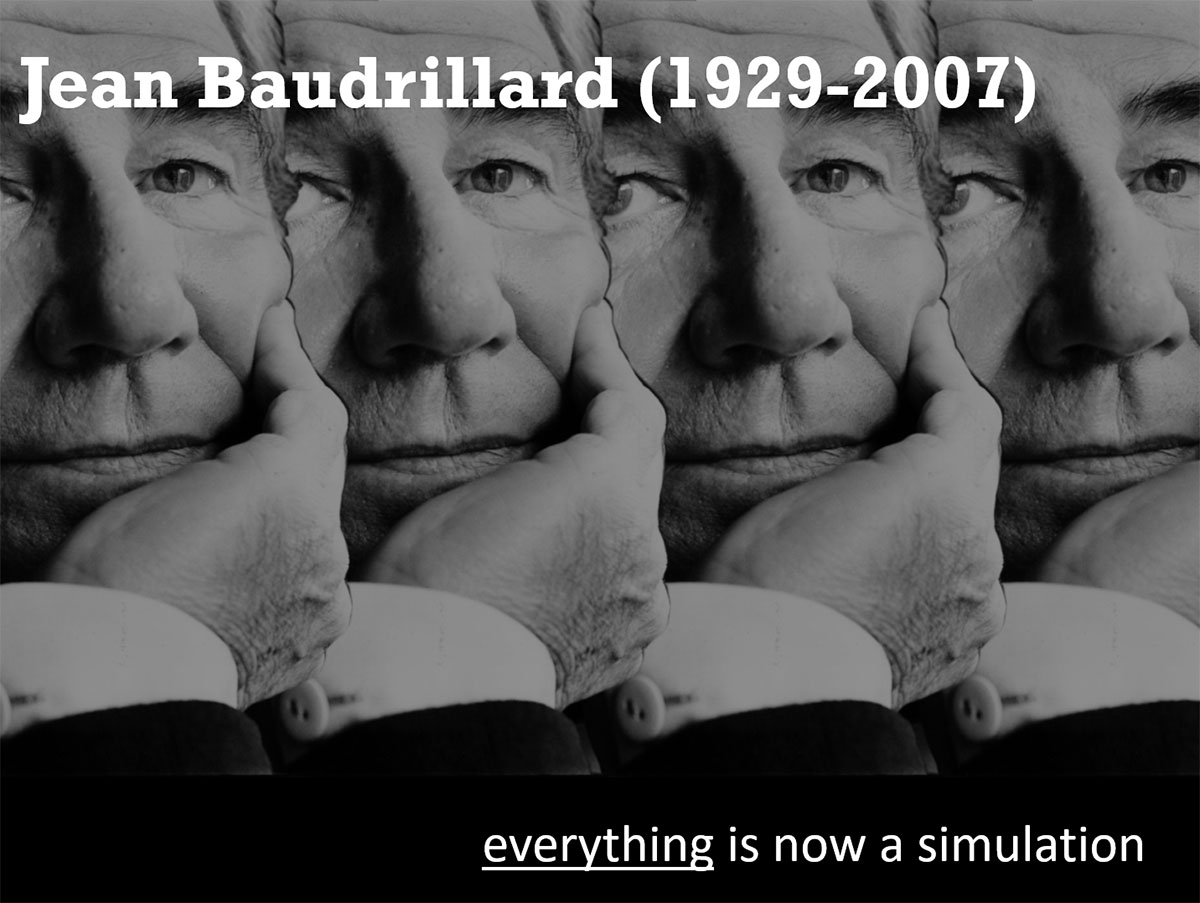

- Hyperreality (Jean Baudrillard)

Hyperreality is a way of talking about the fact that a typical person's "reality" in 21st century North America is a mix of lived experience and impressive and influential media, and that the media itself is a confusing mix of images and stories: real, fictional, edited, packaged, or even downright fake - all coming to us in much the same way - through screens.

A lot of what we treat as real is actually a mediated simulation rather than reality itself, and we start to try to recreate the images we see, even though they are often not realistic or really true to lived experience as it happens outside of media.

This week's lesson looks at something almost everyone has thought and worried about at some point or other: how much time and energy we spend consuming visual media - streaming series, movies, ads, news, YouTube videos, TikToks, Instagram, etc etc etc. The lesson revives some arguments from the 20th century culture critics, made before there was social media and mostly before the Internet, and asks you to think about those arguments and whether they could still be relevant or maybe even more important than ever in today's world.

Electronic sound and video media have only really been a thing for the last hundred years or so. Movies were being made for the public in the first decade of the 1900s and became more common during the 1910s. By the 1920s, they were big business and a common source of entertainment for many people in North America, Europe, and some other parts of the world.

Radio became common in the same general time frame, and phonograph records also came of age during the first two or three decades of the 20th century.

Television only became common in the 1950s. By the 1960s, it was unusual for people of even lower middle class income not to have at least one television set in their homes. At one point during my childhood in the 1960s, we had three sets, one of them in my bedroom (I was a "spoiled" only child, at least in terms of consumer goods).

From the beginning to the end of the 1900s, the average North American went from consuming almost no electronic media, to spending a lot of their time listening to radio and records, watching television and going to movies, and eventually surfing the web.

Social critics have been concerned from the start about the rise in the consumption of "media" by their fellow citizens during this century. It has often been argued that electronic media consumption has a tendency to dumb people down, compared - for example - to reading books, magazines and newspapers. Reading, it is assumed, encourages critical thinking, reflection, and the cultivation of one's imagination in ways that watching television may not.

Anti-capitalist critics meanwhile have argued that our entertainment media tend to be an extention of the consumerist demands for production of commodities that can be bought and sold for profit and that in turn bolster the status quo of our capitalist worldview. Think of the multi-million dollar Hollywood movies, for instance, or the ads one had to watch on tv, or the subscription fees for streaming services. While a Netflix series may seem like an escape from the work one had to do all day, in many ways it is often no escape at all from the worldview that makes our work lives seem inevitable.

Is it a good thing that many of us spend so much time viewing images and video in our lives these days? Is it a bad thing? Is it a dangerous thing for the future of humanity and democracy? These are some of the questions the writers we'll be looking at in this lesson are asking themselves - and us.

The Society of the Spectacle

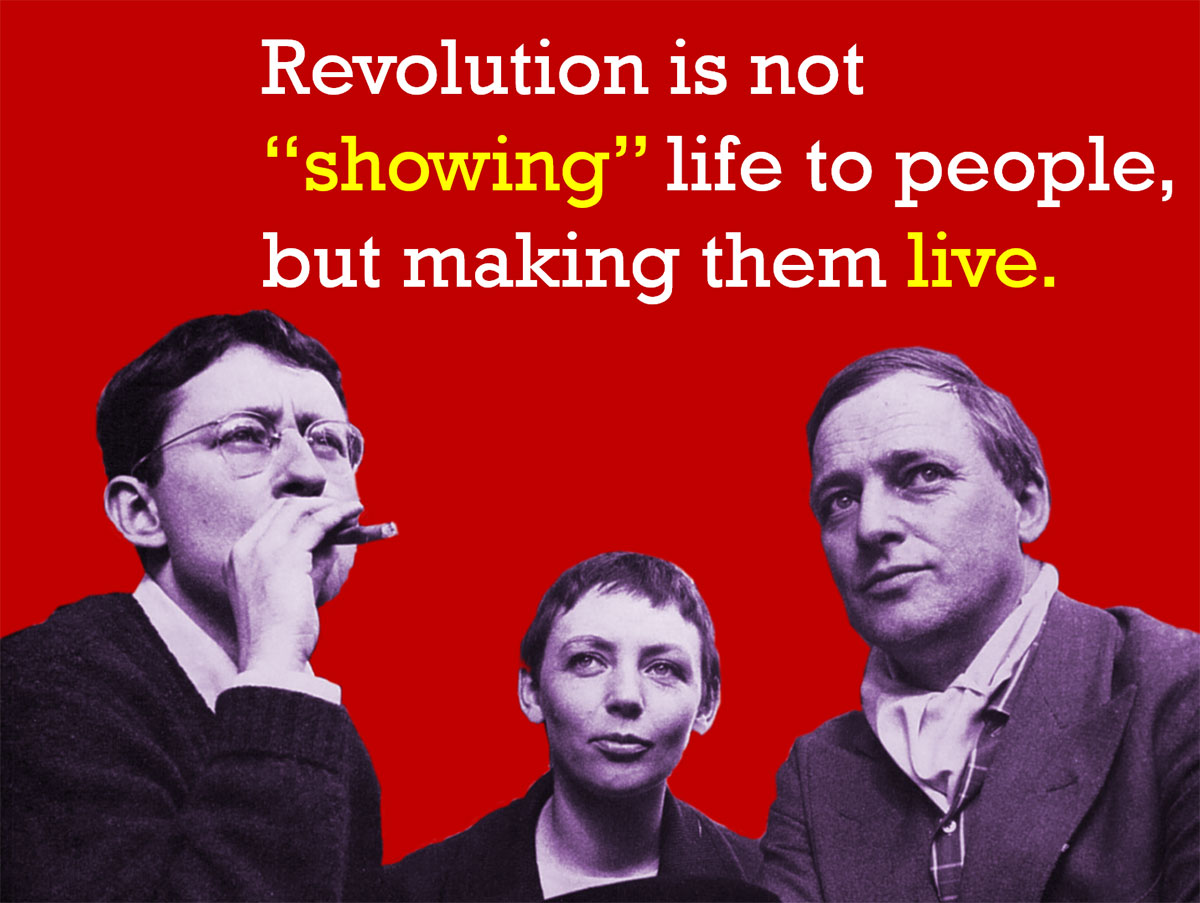

The Situationists were a loose collective of artists and activists in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, who thought that the world in which everyone worked all day and then went home and watched tv on the couch all evening was a gross mistake. They were inspired by Marxist and post-Marxist critiques of Western culture in general, and argued that industrialization, consumerism, and new broadcast media of the 20th century had together perverted human relationships in an unhealthy and unnatural way.

Guy Debord and two of his fellow artistic revolutionaries.

Previously our relations had been directly with each other and with nature, but we now we increasingly related with each other through manufactured objects and images. For these critics, "All that once was directly lived has become mere representation" (Debord, The Society of the Spectacle, 1967). In other words, all human life is now mediated by products and unreal fictional or fictionalized images. Products, consumer goods, brands, corporate and government propaganda, escapist fantasies, unrealistic materialistic ideals, partial images of reality created for the sake of entertainment or sensationalism - all of them manufactured for the rest of us by professionals working for companies who want to exploit us - had come to replace authentic social life, work, and leisure.

Guy Debord was the central Situationist. He and his fellow activists believed that "everyday life"- life lived with other people doing meaningful practical tasks like making meals or working together - doing labour that was meaningful in itself, producing something of material worth (really material, not "materialistic" like a designer garment or handbag), was the natural and healthiest state for the human animal. They argued that with the industrialization and compartmentalization of work and the invention of manufactured commodities human life had changed - and not all for the better. The Situationists believed that the proliferation of endless images in mass media, clogging any clear view of non-mediated reality, had changed our human "reality." The emerging culture of television, which encouraged people to forgo social relationships in order to sit at home on their couches and watch packaged human interaction as a "show," had brought about the emergence of a "Society of the Spectacle." We no longer engaged in life directly and participated in society out in the world most of the time: instead, we sat back as spectators in our living rooms and consumed the "life" that was projected on our screens for us by the "culture industry" that creates our manufactured media.

Before the triumph of the Industrial Revolution, most human beings had experienced life directly and participated in it. We laboured to grow the food that we would later eat. When we were done working for the day, we ate dinner together, talked, played games together, made music for ourselves, went to church, worked in the garden, went for a walk, and so forth. We participated in culture and nature.

In the 20th century, however, people living in the developed and wealthy parts of the world were able (and encouraged) to experience life in a passive and non-participatory way, through consuming film and broadcast media, television, advertising, brands, images. Instead of playing sports, we sat and watched spectator sports on television. Instead of making music ourselves, we listened to music made by professionals on records or on the radio. Instead of doing a lot of things we would have done ourselves in the past, we sat back and watched a manufactured spectacle of "people" doing those things (or simulating doing things) on screens for our passive entertainment. We could feel that "life" was not something we were subject to ourselves, but something we were disconnected from, in control of (as long as we had the remote). The mass media was a crucial part of the consumer society. We were not just consuming products; we were consuming images of life, rather than fully living life ourselves.

The Situationists felt that the wealth of developed nations had led to a meaningless work life and alienated leisure time for the average human, filled with vicarious dreams of the "life" they saw on television and in ads. The Society of the Spectacle contributed to the emptiness of modern existence, because it made us passive, isolated and detached, inadequate-feeling, and driven to greater consumption and escapism, in hopes of somehow being "like the people on TV" rather than living our own lives realistically.

A more recent leftist critic of consumer culture, Noam Chomsky, has talked eloquently of how he personally believes humans actually want to do things, not just be spectators, and how he believes an incredible amount of energy has to be expended by Hollywood, advertisers, and other manufacturers of mass culture to convince us that the world represented in the media is fascinating and important and that we will find happiness and success in consuming commodities and mainstream entertainment products, living vicariously through consuming media.

I don't know whether I really believe that the working class people of Chomsky's youth read books and went to see Shakespeare plays, but I don't think he's just a nostalgic fool either. I do believe that most people are happier and feel more alive when they are doing something, creating something, accomplishing something (tinkering with an auto engine, say) than when they are watching other people do things as passive spectators.

Tomasz Fularksi, Pride 1

Of course now we have the vicarious spectacle of watching people do crafts on TikTok, rather than doing them ourselves, dancing, playing with a pet. In a sense, with the Internet we have a much richer and more "real" vicarious spectacle to enjoy, from the comfort of our disengaged couchdoms. Does watching people make a meal or carve wood inspire us to do those things ourselves, or are we happy just to stand by and watch, consume without producing? Enjoy without participating. Partake, but only through voyeurism?

Vicarious enjoyment means watching or hearing about someone else doing something and somehow imaginatively identifying with them and getting some of the effects of doing it oneself, even though one isn't really doing anything (except sitting in a movie theatre, lying on a couch, or staring into a phone on a bus). It's strange, if you think about it, that people can lie on the couch watching a crime drama and get stimulated through some kind of vicarious identification with onscreen lovers, adventurers, action figures. That vicarious identification is superbly satirized in the Simpsons "couch gag" sequence "LA-Z Rider" (a take off on the old tv series where a computerized car helped David Hasselhoff solve crimes (Knight Rider, 1982-1986)). Here, a motorized couch assists a fantasized version of Homer in experiencing a Miami Vice kind of exciting, sexy, fast-paced "life."

Amusing Ourselves to Death

You may say that it's nobody's business but your own if you want to kill time your whole life watching other people live, or simulate living, instead of living more yourself. But many critics have argued that our addiction to the Spectacle can affect our behaviour as members of society in a negative way. In other words - to extend what Clifford argued - that our private consumption of escapist media can impact the lives of other people, not just our own.

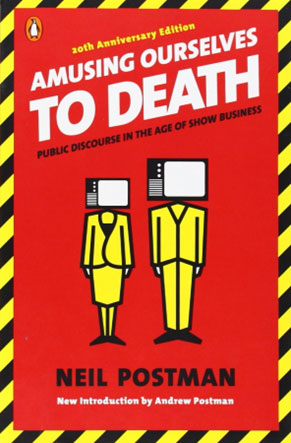

Many critics apart from Noam Chomsky have worried about the influence the mainstream media have on democratic citizens. They fear that overconsumption of these mostly showbiz "products" encourages people to become passive, dumber, less hopeful about social change, more "materialistic" (consumerist), and more escapist, and that these are bad things in a democratic society. In his groundbreaking book from the 1980s, Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985, but still a relevant read today), Neil Postman argued persuasively for the negative effects the broadcast media have on the depth of knowledge and understanding citizens have of their country, their world, and their government, and perhaps more importantly on their ability to tell reality from entertainment.

Looking at the state of American television and the consumerist Society of the Spectacle as an "outside insider," the great African American writer James Baldwin suggested that America's addiction to escapist media actually stands in the way of making America what it wants to be. The media are an unreal narcotic distraction from political and immoral realities that America needs to change rather than distract itself from:

Neil Postman published Amusing Ourselves to Death in the 1980s, before the Internet. The most common and popular way for people to learn about the world at that time was through television, the manufactured medium of which James Baldwin was so critical. Postman thought that the focus on entertainment was a dangerous political change from the world before television, when most people spent much less time consuming electronic media and had to read to find out about the world – books, magazines, newspapers.

The medium of print, as Postman saw it, conveyed the complexity of reality better than television. Reading forced a person to participate actively in making sense; it forced them to use their imagination and to think and spend time understanding. It forced them to pay attention and presumably take what they were reading more seriously.

Television, on the other hand, shows you "reality" in a way that books and newspapers can’t; but what it shows you is always a highly partial, edited, packaged quick slice of reality, if it is reality at all. The people who make television are largely focused on entertaining you, not informing you, not making you think, or giving you a full argument or multiple points of view. They are also, primarily, focused on making money. And to do that they know they have to keep you entertained. Since we receive the news of real things through the same medium and packaged in much the same way as we receive drama, comedy, far-fetched fiction and mindless entertainment in TV shows, it may encourage us to see the real things in the news as unreal and as further occasions for entertainment as well. Television makes unreal things look real and real things look unreal.

Many people followed Donald Trump's election, for instance, as ironic postmodern spectacle. It is like an episode of The Simpsons (It was one!). Except that the Trump presidency was not an episode of The Simpsons: it was real. Some people don't see that, don't care, or would argue philosophically that it's not real. They've never met Trump, for instance. "Trump" is mediated and packaged image or a semi-fictional personality, not a real person.

I remember when my grandmother told me she was going to vote for former movie actor Ronald Reagan for president and added "He's such a handsome man!" Reagan won the election.

Television is focused on slick images, a fast pace, sensationalism and entertainment. Postman thought it often packaged even real and important things as entertainment, and this encouraged the audience to think of these real things as less real, more like the unreal things that made up most of what was on television - and to feel the same about them. Television didn’t make complete and logical arguments; it made "shows" or "ads" out of its images of life, even when it wasn't literally trying to sell you something. The programming, whether a sitcom, a political debate, or a news broadcast, is to some extent seen as "filler" by American corporate broadcasters. What they are focused on broadcasting is actually the ads, and the product they sell is actually the eyes of us viewers, sold to advertisers. (This model is also the one commercial social media platforms have adopted.)

Television as a medium encouraged passive consumption of its media as entertainment, and any real and serious things it tried to tell people started to be experienced as just more slickly presented images, just more entertainment.

Reading about stuff, paradoxically, had conveyed reality more fully than seeing images of that reality portrayed on television does. When reading a book, you had to think, analyse, understand, and see the complexity of reality more fully. You had to participate (through reading) and make meaning. What's more, it was harder to confuse the representation of reality in the book with reality itself. Video looks like a window on reality; a page of a book doesn't - or at least not in the same way.

The Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan famously said "The medium is the message." What he meant in part was that we get a different communication depending on the medium we receive it through. "The same message" is experienced and understood differently depending on how we receive it (reading, listening, watching video, etc). Adam Holzapfel, a student in my Technology and Social Change course, drew attention to a classic example of this in one of his discussion posts:

In the 1960’s political race between JFK and Nixon there was a televised debate and people who watched it on television believed JFK to have won the debate because he used makeup to prevent sweating, was more attractive than Nixon and overall, better composed when speaking. However people who listened to this debate on the radio believed that Nixon spoke and sounded better and therefore won the debate. This goes to show how much technology had an impact on election because if these candidates were only presented through radio Nixon would have won. (emphasis added; Kennedy won that election; Nixon was elected president later on of course)*

Reading a book, one perceives things differently than listening to it being read to you, or the same material in a podcast, or a YouTube video, or on tv, or in a meme. Each medium alters the message and how it will be received/perceived through the nature of how it communicates information.

Worrying about television, Neil Postman made several hypotheses about the political effect of that medium on its audience; I have summarized some of the more important points below.

It’s true that we now have the Internet, a more interactive and potentially more realistic and creative way of getting at reality through electronic media. But the people of today here in Canada have had their expectations of the media shaped by the model of escapist consumerist entertainment that television made normal; hence our "selfie" culture in which everyone wants to present themselves as a packaged media celebrity, and now real people's lives are treated as escapist entertainment as well.

Please consider carefully some of Postman's concerns from the 1980s about our entertainment-focused media:

1. Mass media replaces complex ideas with simplified images. "A picture is worth a thousand words!" But is that really true? An image gives a powerful, but incredibly partial and emotional, glimpse of what is always a more complex situation. It’s fast and easy to see an image and get a message, but it requires no thought or consideration and focuses on a single emotional or aesthetic aspect of what it represents.

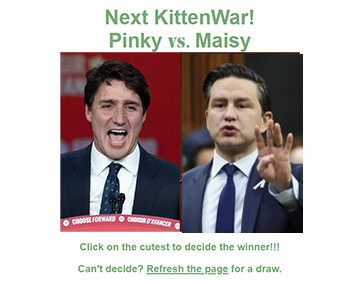

2. Mass media replaces positions with personalities. Positions (points of view that are open to argument, revision, and critique) require people to understand and think about them. It is easier to respond quickly and instinctually to a personality than to understand and reflect on a set of ideas. The mass media cater to this with the focus on celebrities and personalities (who are "relatable" and fun, or seem sexy or handsome or powerful or classy, etc), rather than ideas or policies (which are complicated and difficult and require thought).

Postman argues that most voters will not take the time to study and fully understand the parties and positions that the leaders represent. Instead, they often vote for (or against) the person (their image), based on whether that figure has a "look" or personality that they like, or find impressive, feel they can trust, or seems like them. Appearance can matter a lot in our media marketing reality. But behind this image are important policies, platforms, programs for change or against stasis.

Perhaps almost all politicians have become dishonest showbiz personalities, but I remind people that they usually do still stand for different values. It is dangerous to vote for personalities. This isn't Canada's Got Talent or a high school popularity contest. Rather than thinking about how Justin Trudeau or Pierre Pollievre "strikes" you as a personality, you should have a clear understanding of the policies their parties stand for.

3. Mass media replaces arguments with ads. A slogan like "Make America Great Again!" is an emotional rallying cry, rather than a plan of how the world will be affected. People are often happy to have their messages quick and easy and this leads to the tendency of the media to try to "sell" them things in the simplest and most one-sided way. Instead of a public discussion of goals and a realistic analysis of who will benefit and suffer, appeals are made at the most basic and unthinking level. Most of the public is also happy to have this quick way of deciding about a difficult and complex decision: loved their ad!

4. Mass media replaces active understanding with passive entertainment. Unlike reading a book – even an escapist fantasy novel – movies, ads, and television don’t demand anything from you in consuming them. You don’t have to use your imagination or try to understand what the author is telling you; you can just sit back and take it all in, uncritically and uncreatively. Or ignore it. Some people, like Guy Debord, argue that this leads to a view of oneself as a consumer and a mere watcher of culture. It discourages attention or involvement in political matters and, again, discourages thinking.

5. Mass media is too often escapist, distracting, fake, unrealistic, and exploitative.

So much television content is packaged escapism that Postman thought we had started to treat our news and serious political content that way as well. Like fiction, it is generally about people we don't know and will never meet. In a certain sense, none of it is real in our own lived experience. All of it is packaged and mediated through a screen. It is easy for us to ignore the seriousness of politics and to consider it as discontinuous with our own lives when we experience it mainly through a screen.

Postman was most worried about the political ramifications of treating everything as quick and uncomplicated entertainment. He thought the system of liberal democracy required citizens who were engaged and thoughtful, not citizens who turned everything into meaningless escapist entertainment. Many educated people around the world today are afraid that democracy is in a crisis. Do we in Canada still want freedom to influence our government's policies, do we think we still can, or have we decided it is hopeless and we just want to wallow in the entertainment possibilities of politics as delivered to us through the media? Certainly, the United States has increasingly seemed to find it difficult to make this distinction, and our most recent televised debates here is Canada haven't been any better, just less captivating as entertainment.

Welcome to the Desert of the Real: Hyperreality

The lesson on Plato's Allegory of the Cave hinted at how hard it is to know if something is real, and also opened the question of whether we actually want more reality in our lives, or whether we even can get it if we do want it. Few people at this point in history are seriously interested in giving up on the consumption of media entirely, and yet media is all - in some sense - shadows on the cave wall. One final modern theory proposes a new way of talking about the hopelessness - perhaps - of getting outside of The Cave or escaping from the Matrix: the concept of hyperreality.

The term hyperrreality was coined by the challenging French intellectual Jean Baudrillard, and has been taken to suggest different things at different times by Baudrillard and his interpreters. Baudrillard is "postmodern" in that he does not ultimately believe we ever get to reality. Every attempt to grasp the realness is false, a simulation of reality. It is a representation of reality. As human beings, we live in representation, not in reality.

Our reality has always been partly made up of symbolic representations really, since we started drawing on cave walls or using language to describe the rich berry bushes we discovered on the other side of that hill - those are representations of reality, not the thing itself. But some people worry that maybe hyperreality - our confusion of reality with symbolic or fictional representations of reality - has been "getting worse," because we struggle more and more to nail down what is real, and that distinction is less and less obvious.

Hyperreality is about the fact that human consciousness does not easily distinguish reality from a simulation of reality, and can accept mediated experience as at least as important as directly lived experience. This becomes more disturbing in societies like ours where emerging technologies present more and more realistic simulations of reality, and we spend more and more of our time with those simulations of reality rather than with reality itself. Eventually, what we mean by "real" tends to become what is reproduced in media, rather than anything we have experienced directly - a mass-reproduced simulation or image of something supposed real (in some sense). "Reality itself founders in hyperrealism, the meticulous reduplication of the real, preferably through another, reproductive medium, such as photography" (Baudrillard 1976).

Perhaps this is an inevitable aspect of human "progress." At one point Baudrillard proposed four stages of imaginary/symbolic representation – representation turning into what he preferred to call simulation – in human culture. It may be helpful to think of these stages in very basic terms as following upon one another from the prehistoric period up to the present day.

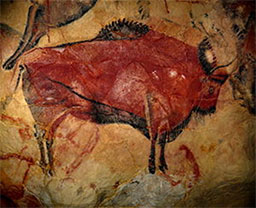

Before there was human culture and language and representation, presumably, there was a bison there in reality (for example). But we can't talk about or understand the bison except in representation. If the bison is trampling you, maybe that's reality. But your story about the bison, your ideas about the bison, your picture of the bison – that is always a representation, and the bison itself is no longer real (physically present, trampling you).

Stage One

Stage One

Originally, when we copied something, it was a copy of a "real" original. We painted a bison on a cave wall – it represented and reminded us of a real bison, which we would like to hunt down and eat (presumably – I don't actually know why cave people painted bisons on the walls). We probably agreed that the bison referred to something in the real world, though it was actually just a composition of colours on a cave wall.

Stage Two

Stage Two

As the world progressed, we started creating images and symbols that were not faithful copies of reality, but which still hinted at something "real" in our fantasies. Nobody has a penis that big, but penises do loom very large in some of our imaginations, as Freud and others have shown. The image points to, though it perverts, a reality.

Stage Three

Next, the proliferation of imaginary symbols comes to mask the fact that what they refer to does not exist anywhere actual. The symbol may be only a word, since there is no physical original to copy. We have a word for God and a word for justice, but these words may not directly represent any thing that is or was actual, physical, real in the earlier sense. If we try to represent God or justice we can at best use a metaphor or something physical to suggest what we feel about these things. That is because they are not real in the same sense that the bison was real.

Next, the proliferation of imaginary symbols comes to mask the fact that what they refer to does not exist anywhere actual. The symbol may be only a word, since there is no physical original to copy. We have a word for God and a word for justice, but these words may not directly represent any thing that is or was actual, physical, real in the earlier sense. If we try to represent God or justice we can at best use a metaphor or something physical to suggest what we feel about these things. That is because they are not real in the same sense that the bison was real.

Stage Four

Finally, we are happy to copy and symbolize the copies and symbols themselves; there no longer needs to be an "original," a real-world referent, or a material thing or being that corresponds to the copy. Copies of fictions are just as easy to work with as copies of real things. We come to inhabit this world of copies without originals. That is what human culture mostly is. A Matrix of real simulations of made-up, simulated unreal images.

Virtual reality and hyperreality

Today our higher-tech, video virtual realities are a lot more seductive and possibly more confusing to our senses and emotions than the ones in books or painted on cave walls. And with more technology they will presumably become even easier to mistake for embodied reality - or they may completely replace it, assuming we can stay alive while detaching entirely from our physical existence as animals. RIght now virtual reality is not bad at simulating visual and audible realities. In a 3D movie or immersive video game we can receive many of the same stimuli and cues we get from embodied reality. When the computers can simulate the sensory input of the other three senses as well, we will decidely have more than a testing toe in The Matrix.

In the future (assuming we make it there, and somehow all have the wealth and leisure we will need to enjoy the luxuries of technology!), will we each live in our own simulated world, which are just as good as - or better than - the real one? It's interesting that it seems to be those with the least difficult lives, with the fewest "real" problems (food, shelter, etc) who are most inclined to an "escapist" response to reality. We are privileged to have the leisure to escape, even though our reality is pretty cushy. Perhaps humans did not naturally evolve to be creatures that have so much leisure time and so little need to engage with natural reality. The Situationists worried about the isolation brought about by staying home and watching tv, and Neil Postman considered the media to be an alternative to engagement with other people. Could individualized fictionalized virtual reality actually take the place of real world socialization and interaction with real other people?

Hyperreality is about the irony that most of us both "know" that a vast amount of what makes up our consciousness is somehow not real, and yet we still care about it deeply, and even at some deep level usually care whether it's real or not, or would like to be able to tell the difference. If you really don't care whether something is real or not, then the concept of hyperreality will be meaningless to you.

The Spectacle by nature flattens out the clear distinction between real and fictional. Media images and television shows tend to package both real and fictional things in much the same way (this was true even before the advent of "reality tv"), and this may add to the increased tension or trouble in the hyperreality of our existence in the modern world as well. Media all comes to us as hard bright unfeeling images, potentially entertainment, whether on tv or through our phones, whether an episode of Friends or news footage of real carnage and suffering.

Social media and the simulation of reality

We don't live in the television world of Neil Postman and the Situationists. Are their concerns about The Society of the Spectacle still valid in the 21st century? Are things better, worse or the same as they were half a century ago?

Is the media Spectacle perhaps becoming less "unreal" now that it is a potentially equitable social spectacle instead of a narrow corporately-generated one like television was (I like to think so)? Or is the real still getting more and more replaced in our lives by the "real-looking" respresentation of Spectacle (yes, that too). Can technology bring us back into contact with one another's reality by breaking down the barriers of time and space and creating a true communion of humans online - democractic, engaged, clear-sighted, awake, informed in ways that were impossible before these breakthroughs? Or does it leave us deluded in our own mediated echo chambers, and happy to treat everything as a simulation or an occasion for entertainment?

Is it possible that all our technology and the pervasive mediation of so much that we experience in our "reality" is divorcing each of us further from reality all the time, giving us more and more unreal experiences that we are happy to take for our reality, buffering us from authentic human interaction with real other people, making real things look more and more like unreal images and unreal things seem more real? One of the ideas about hyperreality involves how we try to simulate in real life the simulations we see in media. And of course a growing number of us are actually trying to turn ourselves into media to feel real, from basic Instagram posts to showbiz influenced influencers. Maybe we are more and more trying to turn our real lives in embodied reality into simulations of the phony Spectacle images we consume all day.

A medium is something between you and someone else. Originally, communications media were thought of as a way of getting a message from one person to another (originally, that was what a telephone was!). Ideally, the communication would be as free of noise and manipulation as possible. But maybe the media are inevitably something between us and reality - even between us and each other! A screen. One of Neil Postman's points could be summarized: "Television makes real things seem unreal and unreal things seem real." Is that even truer of your phone? This is how hyperreality is a problem for those of us who are troubled by it. We want reality, but we can only get it through shadows. Are some shadows better representations of reality than others, even though they are still only representations of course, or can we never get to anything but shadows? That is the question.

* Apparently, this well-known example is actually a bit of a myth, as it was based on somewhat flimsy data from one survey. In recommending caution, Marie Morelli added, however, that "The myth may have gained some currency from the reported reactions of the running mates. Both vice presidential candidates -- Henry Cabot Lodge for Nixon and Lyndon Baines Johnson for JFK -- thought their man had lost. Lodge watched on TV; Johnson listened on the radio." (Morelli 2016). Poorly substantiated or not, I think we can all easily see how it could have been true.