WEEK 08: You are political

Be sure you understand

- ideology

- the personal is the political

- critiques of various ways of voting

- left and right

- authoritarian and libertarian

- socialist - liberal - conservative

The second half of this course will deal with questions that relate to the national and global sphere: politics, the climate crisis, capitalism, and technology as major forces shaping our world.

Many people will feel that these questions are too large for them to consider or participate in (what should government be like? how can we save the environment? is there a better economic system than capitalism? should technology be controlled, and if so how?). It may all sound out of our control, but ultimately it is human beings who must decide these questions, and you are one of them. Since we live in a democracy, with elected representatives and free speech, your response to these massive issues is part of Canada's response, and by extension part of humanity's.

There are two kinds of people in the world: those who don't want to talk about politics at all and those who want to talk about politics too much. ;-) Whichever you are, I hope you will continue reading and open your mind to thinking more about some basic concepts that are used in discussing politics in democratic countries like Canada.

For this lesson, I will discuss why people don't vote and possible concerns with how some people do vote. I will also review the idea from the reading that our personal lives are, in a sense, political, even if we don't want them to be or don't know it. I will then focus on a few key political terms and encourage you to understand them more deeply and try to situate yourself politically, if you have never done so before, or review your position and how it fits into the political spectrum:

- ideology

- left and right

- authoritarian and libertarian

- socialist - liberal - conservative

We’ll be using a popular web tool – The Political Compass – that works almost like a Buzzfeed quiz, and I'll provide you with a couple of diagrams that try to help you visualize and analyse the political spectrum. The tools, definitions, and graphs no doubt all have their own political biases (although they are trying to be neutral). I make an attempt not to be too biased in my presentation, but naturally I have my own political attitudes, and they will no doubt colour how I present the material.

That’s one of the most important points in the reading by Aileen Herman: everyone has a political position, even if they don’t know what it is and consider themselves “apolitical.” Politics is about power. In particular the power of governments and authorities - and how you think it should be used. “I’m not political” is not really a meaningful statement. It just means you don’t want to acknowledge or think about or discuss your political place in the world. Or you may not even be conscious of what it is. This lesson is meant to be a step in the direction of making you more aware of your political values and how they impact you and other people. For some it may seem simple-minded and elementary; for others it will be largely new or framed in a different way that can give you something to think about, argue with, or memorize and then forget, as you see fit.

Some of you may already be very aware of where you stand politically. But often people - especially young people who have so far been little involved in the democratic proces - think they "don't have any politics." Particularly if that is your case, read on!

Why people don't vote, and some common ways they vote that may be questionable

When you talk to Canadians, many of them will say they are not interested in politics. Though we have higher voter turnout than the United States, 1/3 or more of eligible Canadian voters have not voted in a Federal election during the last 20 years.

The reasons people don't vote will probably be familiar: they find politics “boring” (it can be!); they think all politicians are dishonest (most of them probably are); they don’t think it will make a difference because government does whatever it wants anyway (I don’t think this is true); they don’t think it really matters who is in power (I don’t think this is true either, though it's true that it may not matter that much to you personally). This lesson will invite you to think more about those assumptions, if you have some or all of them.

People may not vote because they are too busy to inform themselves on the issues and policies, because they don't understand the questions involved or how government works, because they don't trust the system to honestly reflect the voters' choices (ballot rigging and conspiracy theories), because they don't believe there is any real difference between parties, because they feel their single small vote is insignificant, or because they don't really feel too personally affected by who is running the government (see below). Each of these attitudes is understandable but also debatable.

Other people do vote, but many vote in ways that I feel can be careless. These generally involve either not thinking real change is possible, not taking political questions very seriously, or not taking their own political voice very seriously, or both. Some examples of ways Canadians may make it easy on themselves when voting, but that I feel are often not very responsible:

They vote for whoever their families have always voted for

"We're a conservative household." "This town has always been a Liberal riding." Obviously, this is in another sense always a "conservative" way of voting, based on continuing a tradition and avoiding change.

They vote for a personality; for whichever candidate they "like the look of"

Voters can be very focused on personalities and their media images and understand little about the policies these figures represent. Voting for a party because the leader wears a turban, or not voting for a party for the same reason are hasty decisions that show little understanding of what else the person stands for. (Although, on another level voting for a party whose leader wears a turban could be a strong political statement of its own; it's not necessarily a statement about the policies he represents, apart from the implicit inclusivity.) Voting for someone because they are good-looking and well-dressed, or because they look like you and "your people" or somebody you wish you were or because they "seem honest" is really a comparatively shallow way of making a decision. (see below, on Amusing Ourselves to Death)

They vote for whoever's ads they liked the best

Without knowing anything about the long-term implications of a party's platform, some people will vote based on the persuasiveness or rhetoric of the campaign slogans, fear created by the party's attack ads, or mere enjoyment or appreciation of the way advertising was handled. (see below, on Amusing Ourselves to Death)

They practice "flip-flop" voting

In Canada, a practice has developed that starts by assuming there can only ever be either a Conservative or a Liberal prime minister; there are only two parties that could ever win. This simplifies things for the voter, but helps keep the same "two-party system" in place. Some people will vote one way in one election and then depending on how they "feel" about how the party in power has done, or how they imagine it has impacted them personally, they will vote for the other party at the next election, because in their view it has to be one of the two parties and it keeps the party in power on its toes if there is a danger of flip-flop. "This hasn't been great, let's see what the other party will do for a few years." "I'm sick of that guy's face; let's try the other guy for awhile." (Generally those two parties have male leaders...)

They vote based on who they believe will save or make them money personally

In modern Western democracies a lot of people have embraced the basic assumption that they are voting for their own interests only. Whether it is money or some other interest, they may vote as if they are the only person that matters, and not care at all about the impact a particular government will have on other Canadians, the other people on Earth, the environment, etc. For many Canadians this focus on personal self-interest is centered around their finances, and they may vote, for instance, for a party that says it will create jobs or lower or not increase taxes, despite whatever other policies the party has.

They vote for whoever they think is going to win

Many people watch the polls carefully, and some take them as a guide to how they should vote. As thoughtless and irrresponsible as it sounds, they may vote for whoever they think will win, so that they can feel part of the majority and the people who made the "right" decision.

Politics as unreal media spectacle

Some of the "strategies" above are connected to our tendency to treat politics (and everything) as entertainment, because of the degree to which we live our lives through media, and can treat all media as entertainment. In the 1980s Neil Postman wrote an influential book that I think is still relevant today: Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985). Postman argued persuasively for the negative effects the broadcast media have had on the depth of knowledge and understanding citizens have, and their ability to tell reality from entertainment.

Postman discussed how mass media culture (he was thinking mainly of TV; there was no social media back then) is mostly shallow and anti-intellectual, and generally appeals to our emotions and our desire for sensationalism. Not just in sitcoms or crime dramas but in news and more serious programming as well, the broadcast media tends to replace complex ideas and situations with simplified images. It tends to promote media personalities rather than thought-out positions (think of Americans electing actor Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, or celebrity billionaire Donald Trump in the 2010s). Instead of arguments, this media tends to give you ads, "pitches." And it discourages active understanding and participation (television is one-way, from the broadcaster to the consumer) and encourages instead passive consumption of simplified, emotional images. In short, it is escapist, oversimiplified, unchallenging, and exploitative. Postman believed people had become too focused on images, and rarely had any understanding of policies or how the political world actually works and what all is at stake.

As a medium, television both invited people to make decisions based on superficial appearances or ads that appealed to the emotions, and also encouraged them to see politics as a somewhat unreal spectacle, to be consumed as entertainment.

The concerns Postman had about de-realization and dumbing-down of politics because of television may still be partly relevant to the world of social media we now inhabit - although obviously social media is more democratic, diverse and inclusive, participatory, and at times thought-provoking than televsion was/is.

"Strategic voting"

Strategic voting is a more complex question. Because of the belief in the inevitability of the "two party system," many people may forego voting for a party that really expresses their values accurately, because they feel they need to vote against a party that is definitely far-removed their values. I did this myself in the last American election (I'm a dual citizen), voting for Biden because I wanted Trump out. Many other Americans did the same. Similarly, here in Canada, one might vote Liberal instead of NDP because one is afraid of the Conservatives and thinks the Liberals are in danger of losing. Again the two party system seems regrettable, though people with no time for politics like how it simplifies things. Strategic voting is very common, and it may sometimes be wise to vote this way. Some people will decide based on the realistic expectations of how things will go in their riding; others would say you should always vote for your ideals and the situation will never change if you don't. In many democratic countries around the world there are more than two viable parties to choose from. Canada has drifted very much in the direction of the United States, where "there are only two choices," and some people say the choices are not dissimilar enough.

If you don’t care about politics, it’s because you personally don’t have any political problems

I'd like to suggest that one reason so many people don’t care about politics in Canada is that most of us don’t have to. Our government does not persecute most of us, we have lots of freedoms and our human rights are mostly well protected. (Indigenous people are one clear exception to this. Obviously there are others.) At the same time, it may be hard to see government and political policies as directly affecting the private parts of our personal lives that are most important to us. Many Canadians have only two "political" issues that they feel they need to worry about: how high their taxes are and whether they have enough income. People have gotten used to thinking that the only thing political candidates can do for them (or society, or the world) is affect their personal finances. In Canada, as people have started to say, a lot of us have the privilege of not having to care about politics much.

Of course, the further away you are from the most privileged positions in society, the more you may take an active interest in politics. If you are a woman, you may be “more politicized” than a man. If you are a person of colour you may be more attuned to politics than a white person. If you are queer, trans, poor, indigenous, disabled, Muslim, or some other kind of person who has been marginalized or targeted in Canadian society at times, you may well also be more interested in politics. Because they DO affect your personal life. Politics in the broader sense is more than just electing representatives and dealing with budgets. Politics is about power. Aileen Herman quotes Harold Lasswell’s definition of politics with approval in the reading for this week: politics is about “who gets what, when and how.” If homosexuality were illegal - as it is in an alarming number of countries around the world - or you were prevented by law from getting an abortion, you might be more interested in politics. (And conversely if you wanted homosexuality and abortion to be illegal, you might also be more interested in politics.)

"The personal is the political" - The politics of everyday life

In the reading, Herman shows how everything we do actually has a political dimension to it. When we buy a cup of coffee, whether we know it or not, we are acting politically. If the coffee you buy is “Fair Trade” (as all coffee sold on campus at Humber must now be), you can assume that more of your money is going back to the people who grow the coffee, in another part of the world, where – for the most part – poverty is common and there are fewer workers’ rights than in Canada. As you will see, Fair Trade coffee is "left-wing" coffee.

Fair Trade seeks to improve the lives of coffee farmers and producers of other coveted products such as cocoa, bananas, crafts and textiles, by offering consumers an ethical alternative to mainstream trade networks. In particular, Fair Trade certification indicates that the relationship between producers and buyers is direct, that producers are earning a “living wage" and that a percentage of the earnings goes toward grassroots community development (Fairtrade Foundation, 2018, qtd in Herman).

Buying Fair Trade products is a small political action you can take to show support for exploited workers in other countries.

If you prefer coffee from somewhere that is not Fair Trade, and pick one up there on the way to campus, that was in a sense a political act, even though it is not a conscious one, and there may be no political intention in your choice. You may have unconsciously chosen to support a company and a system that exploits people in another part of the world, so that you can have good, inexpensive coffee here. This suggests a more "right-wing" attitude toward coffee. Some people are comparatively poor (most coffee farmers in Guatemala, for instance, where Herman did a field placement) and some are comparatively rich (you, by global standards). That is not your fault or your problem, and you don't expect the Canadian government to do anything about it either.

For many people the only question here is, where can I get a tasty coffee and how much does the good coffee cost me. Focusing on that aspect of the coffee alone is also a political attitude, even though you don't intend it to be.

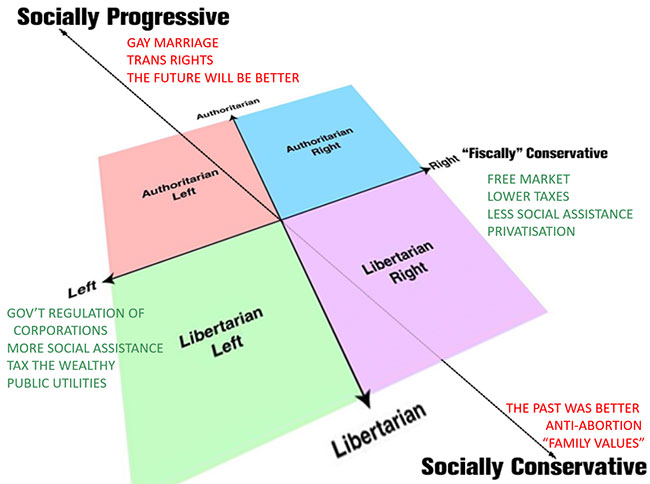

The ideological spectrum

Ideology is a fancy word for a bunch of values and assumptions that tie together to represent an attitude about the world. Everyone operates according to certain ideologies, even if they never consciously think about their values and beliefs and don't have a name for them. The rest of this lesson explores the range of ideological positions in terms of two dimensions. The website you will use to get a rough bearing on your own ideological position is called The Political Compass. It divides up political ideology according to two of the most common axes of political division in the Western world: left vs right, and authoritarian vs libertarian. (Ideally it might actually be a three-dimensional cube, with another dimension - socially progressive vs socially conservative - along that axis. More about that near the end.)

It’s not clear what the political bias of the Compass site itself is, but it has been popular with people from many political backgrounds (though sometimes criticized for being biased or too simplistic to provide exact guidance). The site asks you a series of questions and from your answers it calculates where on its model of the political spectrum you are.

Your exercise this week is to go through the Political Compass questionnaire, save your results, and then think about them, at least briefly. You might want to go do the questionnaire now, do the exercise, and then continue reading. (Click here for the instructions if you want to complete the Compass before continuing.)

The Compass tool seems to originate in Great Britain, but it is pretty focused on the United States political scene, as a lot of political debate tends to be in the Western world, because the United States is the most powerful, wealithiest, and most influential nation. It works reasonably well for Canada, however, which often reflects or comes close to aspects of the American political scene, and practices a somewhat similar form of democracy. If you are concerned with how to vote in our next election, you may also want to go through the CBC's voter compass test, to see what it tells you about your personal political ideology.

The Political Compass divides up the political spectrum according to two of the ways there is the most difference of opinion about how government should relate to its citizens. One axis is LEFT vs RIGHT, which is the question about how much the government should interfere to try to help make people more equal, or make sure they are treated more equitably, especially in terms of economics. The other axis is AUTHORITARIAN vs LIBERTARIAN, which is about how much control the government should have of an individual citizen's behaviour and actions - what should be legal and illegal, how much power the government should have over individual freedom.

For instance, your attitude about socialized medicine will put you somewhere along the LEFT-RIGHT spectrum (should all people have access to free health care? should the rich be able to pay for a higher standard of health care? should prescription drugs be free for everyone, even if it means raising taxes?). On the other hand, your attitude about whether gay people should be able to get legally married or whether sikhs should be able to wear the kirpan (symbolic dagger) at public events will put you somewhere along the AUTHORITARIAN-LIBERTARIAN spectrum.

In a contemporary North American context, the LEFT-RIGHT arguments are most often about money (taxes, government spending, minimum wage, corporate profits) and the AUTHORITARIAN-LIBERTARIAN arguments are often about social conventions and what should be legal or illegal for the sake of safety and morality (things like trans rights, abortion, hate speech, legalization of marijuana, legalization of sex work, etc).

The Compass divides up political ideologies into four quadrants. After you do the Compass exercise, you will be told in which quadrant the tool thinks you land. You may be surprised to see where you land, and you might think the Compass got it wrong. But it’s worth considering what your answers to those questions seem to suggest about your current political values.

The Left - Right Axis

The Left-Right axis suggests how you feel about the principle of egalitarianism. Should people all have the same basic wealth and opportunities, and should the government do things to make that more of a reality? The further to the left you are, the more you are interested in sharing the wealth and protecting or even promoting everyone equally. The further to the right you are, the greater your tolerance for socioeconomic diversity and inequalities.

The three most common political ideologies in the democratic world today are probably socialism, liberalism, and conservativism. Rarer and less frequent are governments where forms of monarchy and aristocracy are still being practiced, sometimes with and sometimes without democracy added. In nations with limited or no democratic system, it isn’t easy to describe the situation with these terms. For instance, China still operates in part as a “communist” (or at least socialist) totalitarian state, but also has an emerging capitalist middle class that likely operates more along the lines of Western conservatism. The government is not a democracry but a totalitarianism and enforces “equality” on some members of society while allowing others to operate more freely, up to a point. It's hard to say it is either left or right in Western democratic terms. In the terms of the other axis, to be discussed in a moment, that government seems to be fairly authoritarian.)

Canada generally wavers between conservatism and liberalism, with occasional local moves in the direction of socialism (the NDP, though it is not strictly a "socialist" party; rather it leans in the direction of what American statesman Bernie Sanders called his platform in the 2020 primaries: "social democracy"). The Green Party doesn't fit neatly into one of these three ideologies, since its focus is on environmental rights. It is generally considered to be similar to the Liberal party in its other policies, but I haven't studied this carefully.

Socialism is to the left, liberalism is in the middle, and conservatism is on the right hand side.

These are potentially confusing terms, as two of these abstract ideologies are also the names of political parties in Canada. Here we’re talking about socialism, liberalism, and conservatism as abstract ideas. Not the names of current parties. See the diagram below, where the approximate position of the NDP and Liberal and Conservative parties are shown on the abstract spectrum of ideologies.

In addition, the term "conservative" is not only or always used for questions of economic equality. It can also be an attitude toward social and “moral” issues. One can be “fiscally conservative” (on the Right in terms of economics) and “socially progressive” (e.g., support queer rights etc). Or vice versa. Conservative parties in both Canada and the United States often appeal both to people who are fiscally conservative and to people who are socially conservative. There is also often a combination on the Left of socially progressive attitudes with a leftist interest in improving opportunities for those who are underprivileged.

At the extreme left of this axis would be a pure communist state in which absolutely every citizen had exactly the same standard of living, rights, and conditions of life. At the extreme right would be a state where various classes or castes had different rights and opportunities, and there was extreme inequality in wealth, freedom, living conditions, and so forth.

One of the ideals of classical "liberal democracy" (the philosophy on which Britain, Canada, and the United States are founded) is that every citizen should have the same rights. In principle, if not in practice, this means that you have the same rights whether you are a man or a woman, whatever your race, whether you are a genius or mentally challenged, and so on. The idea of individual freedom with absolute equal rights is at the centre of this left-right distribution.

Few socialists or conservatives are likely to say that we shouldn't all have equal rights, but they may disagree about how that should be interpreted. A major question is whether, given that we are all born with different advantages and positions in society, and there are social problems like racism and sexism that are not strictly rectified by formal legal rights, the government should work to give all its citizens more equal opportunities, not just equal rights in the strict sense. On the whole, the further left you are the more you want the government to do that, and the further right you are the less you think the government should be involved in making citizens more "artificially" equal in terms of privilege.

The authoritarian-libertarian axis

The other axis largely has to do with how much control of an individual citizen the government should have. This is a different question from the equity/equality one.

Those who distrust government or think it is unnecessary are closer to the bottom, libertarianism. The extreme form of the libertarian view is anarchism, the belief that having no government is best. Those who don't trust people and think a paternalistic government should keep them in line (as well as those who want personally to control their fellow citizens for whatever reasons) are closer to the top, authoritarianism.

Libertarianism on the left might be exemplified by the anarcho-communist ideals of Karl Marx (not the governments that have claimed to be "Marxist" such as the Soviet Union and China), where power would be decentralized and small communes would practice self-governance with collective ownership of resources, land, and property.

Libertarianism on the right suggests individuals or groups who have opted out of democratic action, perhaps forming their own private militias, organized crime syndicates, or other self-interested allegiances, believing government has little to offer them and constrains their natural freedoms and personal ability to gain wealth and power.

On the top half is the opposite extreme: authoritarianism, the belief that the government needs to keep citizens in line. The extremest form is fascism or totalitarianism, where the powerful people who run the government keep most citizens under control in what amounts to a police state, with pervasive surveillance, severe penalties for those who don't comply, no rights to public trial, no true elections or democratic process, and often corrupt double-standards for those with privilege and influence.

Josef Stalin (left) and Adolf Hitler (right) - two leaders of notoriously authoritarian governments in the 20th century.

Authoritarianism on the left at its most radical could perhaps be exemplifed by the People's Republic of China during its early years, or Stalinist Russia in the 1940s and 50s (in principle at least): a strong state supposedly makes sure that every citizen has a similar quality of life and it controls any attempts at creating non-state-sanctioned privilege. Of course, there was much internal abuse and privilege still operating in these countries, but that was their stated doctrine at least.

Extreme authoritarianism on the right at its most radical suggests Nazi Germany, with its clear racist policies of white supremacy and control of the population through fear, policing, and propaganda. Privilege based on birth was not just accepted, it became the model of a hierarchical society in which the "Aryan" white people were on top and others were excluded to the point of expulsion and eventually murder. Power was centralized in the government's leadership and enforced on the population with policing, informers, surveillance, and other tools of fear.

If you think the government should have little say in what an individual does (as long as they aren't hurting someone else) you're more libertarian. If you think the government should dictate individual behaviour (usually for a "moral" reason, because of safety, or on account of an "ideal" such as fundamentalist religious values or white supremacism) you are probably more authoritarian.

For instance, should there be laws around a "victimless" crime like gambling? The more libertarian you are, the more you would probably think gambling should be available to anyone regardless of age, anywhere, at any time. The more authoritarian you are, the more you probably think there should be limits, or perhaps it should be outlawed altogther.

Similarly with matters such as sex work, abortion, age of consent, and other questions that people may associate with morality. Former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (Justin's more famous father) once said "There's no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation." This expresses a libertarian attitude: what consenting adults do in terms of sex is not a matter for legislation. You can contrast this attitude with the authoritarian policies of governments like Yemen, Iran, Singapore, Brunei, or many nations in Africa where homosexuality is illegal. In the most extreme cases, it can be punishable by death.

This video by popular YouTuber jreg - though it should obviously not be taken too seriously or used for study purposes! - provides a more entertaining caricature of how people in each quadrant may be seen by those in the other quadrants.

These are caricatures, and I would say that Jreg himself is coming from the bottom left quadrant, so the characterizations should be taken with a grain of salt.

The makers of the compass have attempted to place the five most popular political parties in Canada on the compass and came up with this placement:

I'm not entirely convinced by how high up the authoritarian scale the Liberal and Conservative parties are here, but I think this almost certainly correctly shows the order of our major parties from Left to Right.

The Political Compass focuses on the two axes of left-right and authoritarian-libertarian, but obviously politics and any individual's personal ideology are not so abstract. You can be an anti-authoritarian white supremacist, and you can disapprove of gambling without wanting to control people's lives in other ways. Most of us are probably libertarian about some things and more authoritarian about others.

Important moral/political dimensions are left out of the compass, because it is (rightly) focused on your view of how government should be. For instance, the range of social attitudes between conservative and progressive are not really identical to either of the two axes in The Political Compass. As I briefly mentioned, there are really two kinds of conservativism: fiscal conservatism, which focuses on the government not being involved in the capitalist economy, not regulating personal wealth, not taxing the wealthy to support the poor or changing the rules of trade etc, and social conservatism, which focuses on issues some people would define as "moral." Social conservatism wishes to resist changes in social norms, and for the government to make certain social behaviours illegal or underprivileged for the safety and good of those practising "more traditional" lifestyles. The conservative parties in the U.S. and Canada atttract both kinds of conservatives, but it is possible to be socially progressive and fiscally conservative, or vice versa.

Someone like me, who gets categorized as both left and libertarian, can be quite happy to have the government become authoritarian when it comes to regulating the extremes of wealth distribution (I lean in the direction of "Democratic Socialism"), but otherwise libertarian when it comes to the social issues (pro-LGBTQ+, anti-racist, etc). So maybe I am a "fiscal authoritarian" but a "social libertarian."

In the popular media, there tends to be an assumption that in the United States and Canada, further left means bigger government, and this is why it seems strange to see the NDP in a libertarian quadrant (and myself even deeper there) and the Conservatives way up in the authoritarian quadrant. So these placements may be more a reflection of those parties' legislative attitudes toward social issues: eg, drugs, sex work, abortion, LGBTQ rights, and so forth.

Things are more complex than these two axes, and the Political Compass questionnaire is not a scientific tool providing refined analysis. The little tool provides a basic impression of a person's ideology that people who study politics more seriously will find simplistic and potentially misleading. But it does at least begin to situate you within the most common political debates and attitudes in Canada today. Every time I've taken it, it has landed me in the Left Libertarian quadrant, and that feels right to me, and reflects my own party affiliations.

As I mentioned briefly earlier, when the next election is coming, you may want to take another "compass" test for your own greater understanding. The CBC provides a voter compass that works similarly to the Political Compass we're using in this course, but includes more Canadian issues in the questions. However, it doesn't use the same two-axis quadrant to situate you, instead showing LEFT-RIGHT and PROGRESSIVE-CONSERVATIVE dimensions. Click here to take the CBC test, not for marks, just for your own information. (Personally, I got the same recommendation on which party to vote for using both tools, but yours might come out different!)

I hope you learn something about yourself and your world by exploring these tools and this lesson.

FOR TESTING

- You should know what ideology means

- You should understand Herman's idea of "the personal being political" and be aware of the example she used (coffee)

- You should understand what the left and right axis of the Political Compass is about

- You should understand what the authoritarian and libertarian axis of the Political Compass is about

- You should know which quadrants the five most popular Canadian parties fall into, according to the makers of the Political Compass tool