Personal impressions of colonialism in Canada

Be sure you understand

- Imperialism and Cultural Imperialism

- Indigenous vs settler cultures

- The Three C's of colonialism

- All my relations

- The Doctrine of Discovery

- The Two-row Wampum Belt

- UNDRIP and Bill C-15

- Canada's genocide

Apart from the material in this page, on which you will be tested, you also need to read Jose Kusugak's memoir of going to the residential schools this week: On the Side of the Angels.

If you would like to explore these topics further, the documentary Colonization Road (2016, dir. Michelle St John) is also an official GNED 101 "reading." A couple of excerpts will be found in this page.

Content warning

Issues discussed in this week's lesson include the violence of colonization and its resulting inequities, sexual assault, and other experiences that need to be treated with sensitivity and respect. If you are in need of support, as a Humber student you may access the following resources:

I write this as someone who is not indigenous and who is still learning about indigenous knowledge and history. These are some of the things I've discovered and thought about since I began studying this topic.

I have learned a lot from three good friends I have who are of indigenous background, and particularly one of my colleagues, Mo Riche, who teaches a fascinating and unusual elective about the relationship between humans and (other) animals here at Humber, HUMA 240 Rethinking Animals. (Obviously, anything I say here is part of my own efforts to understand colonialism and indigenous cultures, and Mo should not be held accountable for any mistakes. If you identify as indigenous, I would appreciate any corrections, advice, or feedback you have to give.)

My department is developing courses on Indigenous Knowledge in conjunction with Humber's Indigenous Education and Engagement office, which is a good place to start if you would like to get deeper into an understanding of indigenous experiences, or if you identify as indigenous and would like to find support and connection within the college.

My department is developing courses on Indigenous Knowledge in conjunction with Humber's Indigenous Education and Engagement office, which is a good place to start if you would like to get deeper into an understanding of indigenous experiences, or if you identify as indigenous and would like to find support and connection within the college.

I took a course through them last year, as well as one that is offered through the University of Alberta: Indigenous Canada.

Indigenous cultures and settler cultures

In the social sciences, we refer to what happens when people from one culture move into a region that is already inhabited by people with a different culture as settler colonialism. The people who were there first are the indigenous population and the incoming colonists are the settler population. This can be seen not just in the white European colonization of parts of America, Australia, Africa, and Asia, but all around the world at different points in history and among racially closer groups. For instance, in parts of Africa, one tribe or nation may move in on another one. In Ireland, the English moved in and settled, displacing and subduing the native population, and in Israel Zionists were settlers among what had become the indigenous Palestinian population.

In Canada, we usually understand "indigenous" to refer to the First Nations who were here before Europeans arrived. They had been here for at least a few thousand years. The French and British settler colonists started moving into the territory only in the last 500 years.

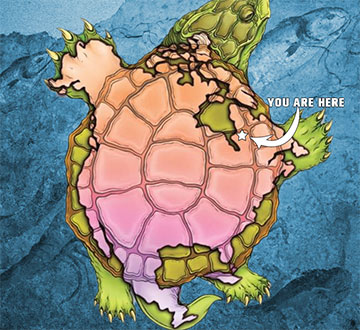

Gradually the overseas kingdoms of Britain and France began practicing colonization of Turtle Island (this is a name given by many indigenous groups to the continent usually referred to in English as North America). The colonization of Turtle Island disrupted the sustainable way of life of the humans who had lived here for thousands of years, eventually nearly obliterating the cultures that were native to this land.

If you look up colonization in the Oxford English Dictionary you will get a definition that already sounds a little nasty: "acquiring control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.” If you asked an indigenous person in Canada, however, you might get a definition more like the words of the writer, academic, and activist Taiaiake Alfred: "the disconnection of Native people from the land, their history, their identity and their rights so that others can benefit.”

We are coming to recognize that it is not just the native peoples that lose out when colonizers overrun another people's land and impose their culture on them. The indigenous people may understand this land, and the larger reality of life in general, in ways that the colonists might have been wise to learn from. The settlers eventually had the power and the will to subdue the continent and its native peoples. When I was a boy we were taught that this was a good thing for humanity, progress. It now seems more like a tragedy to me.

The Three C's

The European colonizers of North America were committed to what has come to be called the three C's of colonialism: Colonization, Christianity, and Commerce. That's the handy catch phrase, so expect to see it on a quiz! The way I see it, though, the white Europeans really brought three key things with them that ensured they would come to dominate the indigenous populations: Technology, Christianity, and Capitalism.

The technology allowed them the upper hand in weaponry, architecture, and other fields that would allow them to win by force. Christianity allowed them to feel justified in their "cultural imperialism" (attempt to take over and replace someone's culture with your own) - they were bringing "salvation" to the "savage" peoples of this continent. And meanwhile Capitalism encouraged them to see the resources among which the native people lived as potential property and sources of wealth. Both the land and the people were viewed by capitalists as exploitable resources.

Christianity, despite its moral messages of brotherhood and compassion, includes within it a view of nature that would have been incomprehensible to the indigenous Canadians, but that tied in well with the capitalist values of the settlers. Near the beginning of the Bible, God sets man up above all the rest of life on Earth and essentially says "take control of it and use it as you see fit!"

... and let [humans] have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth, and over every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth. So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him ... And God blessed them, and God said unto them, Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth. (Genesis 1: 26-28)

In other words, Man is in charge and rules the rest of nature.

The Doctrine of Discovery

During the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church in Europe had also developed a (very un-Christian) view that Christians were better than other humans, or indeed that humans that refuse to be Christian are not fully human. Shortly before the "Age of Discovery" that was kicked off by Columbus's voyages to the Americas, the Catholic Pope had released pronouncements that legalized what has come to be called the Doctrine of Discovery. The settlers often used Christianity as a justification for their encroachment. Early colonists were all Christians, and had no reason to doubt that Christianity was the true religion.

The earliest settlers came with the Pope's guarantee that they had a right to occupy lands where non-Christians were living. During the Middle Ages many Christian powers in Europe had engaged in "crusades" in an attempt to reclaim territory in the Holy Land (the Middle East) from Islamic powers. In Europe, non-Christians were considered enemies of the Catholic faith and as such could be considered less than human. As the "Age of Discovery" began to take off in the 1400s - exploration of Africa and eventually the discovery of America - an official position on lands that were inhabited by non-Christians was put forth by the Roman Church, the central authority for Christian thought at that time.

The Pope's pronouncements led to this “legal” framework called the Doctrine of Discovery. According to these decrees, when European nations "discover" non-European lands, Christian nations have a “divine right” to claim absolute title to those lands. This religious sanction underlies some of the entitlement that early settlers felt in occupying and appropriating territories in North America that were already inhabited by people with different faiths and cultures.

The settler sees himself as special, disconnected from the rest of nature, above it, and free to do as he likes with it. In addition, because of his Christianity, he has a special privilege above other human beings. And as a capitalist, he sees himself as naturally in competition with every other human being, and eager to exploit other human beings and the rest of nature for his own profit. All of this is very typical of the white Euro-American view of reality in general. Power and entitlement led to the eventual success of the settlers in overrunning, exploiting, and ultimately controlling the people who were already here. Thus, part of the Western tradition coming from both Christianity and science/technology is the belief that humans can control and own the rest of life on earth, and should do that.

All my relations

This is very different from how most indigenous people on Turtle Island saw their relationship with the rest of nature. They considered themselves part of it, deeply connected to it. The Lakota people had a saying that has become popular with many indigenous groups today: "All my relations." This view of the world recognizes (as Western science now has) that we are all made of the same stuff, and all at least distantly related to one another. Not just all humans (though that's an important recognition, and difficult for many!), not just humans and other primates, but everything alive on the planet is related (humans share more than half of our DNA with bananas, for instance).

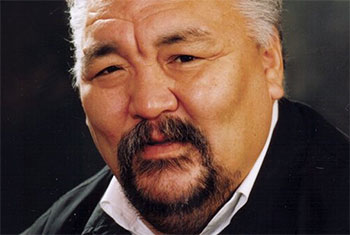

Richard Wagamese (1955-2017)

As the late novelist and essayist Richard Wagamese put it:

"All my relations," means all. When a speaker makes this statement it's meant as recognition of the principles of harmony, unity and equality. It's a way of saying that you recognize your place in the universe and that you recognize the place of others and of other things in the realm of the real and the living. In that it is a powerful evocation of truth. Because when you say those words you mean everything that you are kin to. Not just those people who look like you, talk like you, act like you, sing, dance, celebrate, worship or pray like you. Everyone. You also mean everything that relies on air, water, sunlight and the power of the Earth and the universe itself for sustenance and perpetuation. It's recognition of the fact that we are all one body moving through time and space together.

The European settlers, on the other hand, had inherited a culture where we are all separate and in competition and where some are the important ones and some are the insignificant ones - a hierarchical world. In that world view, white people and Christians were considered the most "advanced" and "civilized" of humans; humans had been made in the image of God and were above the other animals; and our relatives were there to be studied as objects through science, to be controlled by force and by self-imposed discipline; to be exploited for gain; and to be turned into property. These are my own closest relatives who mostly thought this way, but that's how they've come to look to me.

Oren Lyons, a well-regarded indigenous "faithkeeper" in the United States whose talks I have often found illuminating, spoke in the 2024 Bioneers Conference about the web of life on earth as "a community" the way many indigneous people see it:

As with the indigenous view of the other life on the planet as our "relations" (something borne out by modern science as well), the metaphor of the web of life on Earth as a "community" seems to me a powerful and insightful alternative the viewing the rest of life on this planet as dangerous competition or exploitable resources.

The stages of colonization: From Two Row Wampum to Assimilation

Speaking very broadly, I think we could say that the white colonization of indigenous people in Canada moved through a few stages. In the earliest days when settlers were few, European technology was not as advanced, and colonists needed the help of the native people to survive, there was a period of exploration and collaboration. This moved into a period of trade and also Christian evangelism, as there was a significant attempt to convert the "savages" to what the Europeans assumed was the true religion.

In the early days, the settlers needed the help and guidance of the indigenous peoples, and did not want to have to enter into conflicts with them. The earliest treaty between Europeans and indigenous Americans, the two-row wampum belt, was originally intended as and is considered by many indigenous people still to be a legal agreement between European newcomers and indigenous inhabitants to share the land and continue each in their own parallel ways. “Together we will travel in Friendship and in Peace Forever; as long as the grass is green, as long as the water runs downhill, as long as the sun rises in the East and sets in the West, and as long as our Mother Earth will last.”

The two-row wampum was originally a pact between the Haudenosaunee peoples and Dutch settlers. So from a strictly legal view (in the Euro-American conception of law), the belt is not a binding agreement between the later country of Canada and all Indigenous nations, though the Haudenosaunee restated the wampum belt principle in later treaty agreements. It is an early expression of a fair and equitable sharing of resources between settler and native people. Elements of this conception of cohabitation occurred in many later treaties, including the Covenant Chain treaty of 1677 between indigenous peoples and Great Britain and the Treaty of Canandaigua made with the United States in 1794.

I have not studied treaty law or the ways in which treaties have been re-interpreted or ignored for the benefit of the colonizers, but even if the settlers did not always break laws or technically go back on their word in a strictly legal sense, it seems clear that they "went back on" their humanity (and Christian principles) as they moved west and disrupted the lives of the people who had been living there for thousands of years, and then eventually forced them onto reservations and into residential schools. The symbolism of the wampum belt survives to this day as an idea that could be revived.

Many indigenous activists still believe in the spirit of the wampum belt and hold out hope that the principles expressed there can be revived between settler and indigenous nations. In the 2016 documentary Colonization Road, scholars and indigneous leaders discuss the significance of the belt.

Bill C-15 and UNDRIP

The hopes of the indigenous allies in the documentary may sound naive to you, but progress seems to be being made. On June 16, 2021 Canada’s Senate passed Bill C-15, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act (the UNDRIP Act) into law. Canada has now officially adopted the tenets of the 2007 UN declaration on indigenous rights into principles protected and meant to be implemented by federal law. This seems to provide new legal grounding for land claims and could affect many aspects of Indigenous and Canadian life moving forward.

The legal situation may be changing in ways that will be positive for indigenous people in Canada, but the relationship between settlers (and their descendants) and indigenous people may be what most needs to change. Near the end of Colonization Road, the distinguished writer Lee Maracle, who died shortly after Bill C-15 was passed, worries that indigenous people will never feel respected and whole and at home again in what has become Canada. Canada has forcibly separated indigenous people from their languages, their cultures, their families, and their territories in a slow-motion cycle of abuse, betrayal, and trauma for at least the last two hundred years. Indigenous people are still being educated in schools focused on settler culture and values and history and languages, and asked to assimilate, instead of being asked for advice, help, and mutual respect.

A problem of relationship

Part of the ideology of the settler culture in which I grew up assumes that conflict and competition and chauvinism are just natural to the human condition, and to someone who thinks like that, much of what is said in Colonization Road probably sounds absurdly naive. To be hopeful that settlers will really honour indigenous people, justice and fairness, try to make up for past wrongs and engage in sincere fair dealing moving forward, will sound fairy-taleish and unrealistic to many people.

The problem we have here is a problem of relationship, as Maracle says. We Canadians are not really seeing First Nations as equal fellow human beings. The relationship has been one of betrayal, abuse, and lack of recognition. That's toxic, and it would appear to be on us. If you think like I do, then when any human beings (in this case, the European settlers, and now all of us Canadians) turn their back on the humanity of other human beings because of their race or their culture, they are turning their back on their own humanity as well. Many critics of settler culture argue that this is a problem of this culture: we are cut off from the reality of our connectedness to the rest of humanity and nature.

Maracle speaks of the deep intergenerational trauma caused by the Residential School system, and we will now take a closer look at that to end this lesson. As the settlers moved west, they employed whichever of three methods would work best to minimize the interference and influence of the indigenous people: Extermination, Isolation (confining them to reservations), or Assimilation (trying to turn them into "white people").

Assimiliation

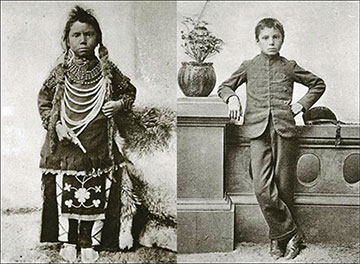

The same boy before and after conversion to settler culture.

When I think of colonialism and assimilation, I often think of it in terms of an alien invasion. I wonder if that was what it was like for the indigenous people of Turtle Island. Imagine that a flying saucer landed in Toronto and humanoid aliens came out of it. They have advanced technology and they claim that they know the true God. You are invited to give up your earthling culture and belief and join them in their worldview. Some would probably resist; some would probably join them. Some would probably struggle and become split in their allegiances and sense of themselves.

The memoir you will read about Jose Kusugak's experiences in the Residential Schools gives us a glimpse of the attempt by the settler government (European-Francophone or Anglophone-Christian) to enforce assimilation. Children were taken from their families to be educated in Euro-American ways of being and the Christian religion. They were taught French or English and encouraged to stop using their own languages.

Jose Kusugak, Inuk political leader (1950-2011)

Cultural assimilation is when people in one culture attempt to convert people with another culture to their own cultural values and manners. Part of the assimilation attempted in the Residential Schools was a continuation of the missionary work of the Christian priests that started very early. Much of it was about teaching the native children English and French, Euro-American manners and customs, and making it possible for them to assimilate into what had become the "mainstream" settler culture of Canada: Christian, Capitalist, and European in everything from dress, to the position of women in society, to the legal system.

Though this program of assimilation - which ran from the second half of the 1800s until the last Residential School was closed in 1996 - tied in with the interests of the settler nation and a racist doctrine that was once notoriously articulated as "kill the Indian in the child," it is no doubt true that some of the people who worked in the Residential Schools were well-intentioned and wished to help the children partake of what they saw as the goodness of the Christian faith and the benefits of settler society. Unfortunately, what they often succeeded in doing instead was to take children from their families, take their language and traditions from the children, and spew out at the end of a few lonely and traumatic years broken and splintered human beings who could not succeed either back among their own people or in white society, feeling they belonged neither place. The trauma experienced in the schools has trickled down from generation to generation. My friend Mo's grandfather was in a Residential School, and he never wanted to talk about it to her. Many "graduates" became suicidal, addicted to substance abuse, or otherwise incapable of leading truly happy lives. Some had been physically or even sexually abused. Some children were subjected to medical experimentation. Most had been treated as unpaid labour. All were estranged from their families and the world view they had grown up with.

There is a sociological concept known as intergenerational trauma. The idea is that traumas that happen to our parents and grandparents tend to trickle down to us and create traumas and trauma-reactions even if we didn't experience themselves. I've experienced this in my own personal life, where the traumas of my parents and grandparents and the ways those have made them behave have influenced my own sense of self and well-being in the world. Virtually every indigenous family with Residential School survivors in their past shows signs of this intergenerational trauma.

Canada's Genocide

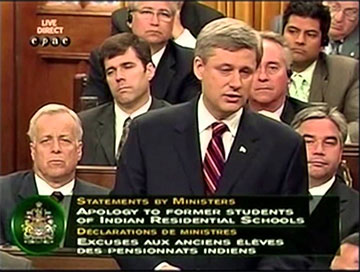

Prime Minister Stephen Harper making a formal apology in 2008 on behalf of the Canadian government for the wrongness of the Residential School system, as part of the on-going attempt at Truth and Reconciliation.

In 2008 the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) started collecting stories of the Residential School survivors from across Canada. In the final report of the commission, the residential school program was termed a cultural genocide. The legal definition of genocide according to the United Nations includes “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

As you will see, Kusugak provides a strangely gentle and open-hearted account of his experiences as a child, wrenched away from his family and forced to try to assimilate to the Euro-American ways. He was not physically or sexually abused as some children were, but he can still convey in his quiet and restrained way the emotional and social violence that was done to him and the other children, the disorientation and confusion, the alienation, and the bitterness he feels about the way his life was warped by this experience, despite his having survived it and become a successful political leader, and advocate for his people and the citizens of the territory of Nunavut that he was instrumental in the creation of. Most survivors of the Residential Schools have found it less possible to turn their anguish into positive action in the world.

FOR TESTING

- Imperialism and Cultural Imperialism

- Indigenous vs settler cultures

- The Three C's of colonialism

- All my relations

- The Doctrine of Discovery

- The Two-row Wampum Belt

- UNDRIP and Bill C-15

- Canada's genocide