The Future of Life on Earth

Be sure you understand

- The various meanings biotechnology can have

- The scientific meaning of "Survival of the Fittest"

- Evolutionary reasons humanity might "be suicidal"

- The meaning of "domestication of biotechnology"

- The reasons Dyson thinks that domestication would be a positive step for humanity

Background questions for this lesson:

- Is the human species likely to prove a "fit" species? Why or why not?

- Does the domestication of biotechnology make sense as a proposal? Why and why not?

- Is more technology always the best answer to problems created by previous technology?

- Should technological possibilities alone determine what we do as a species?

- Who should control powerful new technologies that potentially have global consequences?

Biotechnology is the creative manipulation of life and living creatures, using human-made tools.

When we think of technology, most of today are focused on electronic devices that allow us to communicate and share media, but technology really applies to all the tools and machines humans have invented to make our lives easier or give us more control: the wheel, the bow and arrow, the mechanical clock, the plough, the mill, the gun. All of these are examples of human technology. Any changes that humans make to the workings of nature can also be seen as forms of technology. Dams, crops planting, selective breeding of livestock - these are forms of technology in the broad sense.

The earliest cultures and civilizations of the human species could probably not have arisen without the earliest examples of what could be called "biotechnology": agriculture and selective breeding. Before the invention of those "tools," humans lived by hunting and gathering, in small often nomadic tribes. Once there was farming, there was the possibility to settle down and build something. There was surplus food in storage. There was "leisure time" to pursue something other than sheer survival. Culture is probably a direct result of the cultivation of other plant and animal species by humans. Humans without agriculture are just one more animal, subject to the laws of natural selection. When humans figured out how to practice artificial selection on the other species that were important to us (selective breeding of plants and animals for our use), we got a little bit of an edge on the rest of nature.

Though any use of tools and our intelligence to alter natural life could be considered "biotechnology," when most people use that term they are referring to the science-based manipulation of living organisms that became possible in the 20th and 21st centuries. This is what will be talking about in this lesson. Things like

- Cloning

- Genetic modification

- Stem cell cultivation

Many people assume that biotechnology is poised to explode and eclipse the power we are already familiar with in digital technology (computers, phones, the Internet, Artificial Intelligence). Those technologies work with electricity and cold dead images and data; biotechnology works with the stuff of life itself.

“Survival of the fittest”

The theory of natural selection says that the fittest organisms survive and reproduce, passing on their fitness to their offspring through their genes. But “fitness" is not necessarily about physical or intellectual strength. Fitness is reproductive fitness. An organism is "fit" if it can live long enough to reproduce. Many comparatively weak and unintelligent creatures can do this, most plants for instance. Cockroaches. Their fitness comes from other qualities they possess.

Fitness is also about fitting in with your environment well enough to live long enough to reproduce. From the point of view of natural selection, reproduction is all that matters. If you reproduce, you are fit. If you don't reproduce, no matter how strong or smart you are, you are not going to pass on your genes. Bunnies remain fit by burrowing holes to protect themselves in and being able to outrun many of their predators. They are not fierce, especially strong, or especially smart. But they fit into their environments and can be part of the chain of life.

The scientific assumption is that human intelligence and culture arose by random mutations that increased the "fitness" of homo sapiens when they came along. Thanks to our ability to use tools, to think and plan, and to communicate and cooperate socially we have survived and spread our genome across the planet.

However, as suggested in the lesson on climate change, our intelligence has now allowed us to create a giant global industrial complex that may actually threaten the environment in which we have to live. Perhaps our very intelligence, coupled with our genetically programmed "selfishnss," will ultimately prove our undoing. Sometimes a species spirals out of control in a direction that once worked for it and spoils its own environment.

Is humanity suicidal?

Edward O. Wilson, an evolutionary biologist, wrote a short article in 1993 for The New York Times Magazine called "Is Humanity Suicidal?" In it he discussed the human race as an animal species that has gotten out of control. Our intelligence - supposedly what makes us "above" the rest of life on earth - when coupled with our hard-coded survival instincts (fear, greed, competition) has led to a situation in which we can destroy our own environment, and probably will.

The human species is, in a word, an environmental abnormality. It is possible that intelligence in the wrong kind of species was foreordained to be a fatal combination for the biosphere. Perhaps a law of evolution is that intelligence usually extinguishes itself. This admittedly dour scenario is based on what can be termed the juggernaut theory of human nature, which holds that people are programmed by their genetic heritage to be so selfish that a sense of global responsibility will come too late. Individuals place themselves first, family second, tribe third and the rest of the world a distant fourth. Their genes also predispose them to plan ahead for one or two generations at most. (Wilson 1993)

This suggests that human technological progress has been our advantage for a few thousand years but that it may turn out to be our downfall - because we're not good at thinking ahead or caring about future generations. Once humans got civilization with its excesss wealth, leisure time, etc, we were bound to go in directions that were deluded and unsustainable, still driven by our survival instincts which had evolved to deal with a difficult and fragile existence on the African savannah. Our brains have not evolved fast enough to keep up with the risks our technology brings.

Biologists can show you examples of other species that have "lucked into" situations where their instincts led them to overexploit their own environment, ultimately making it unlivable for them.

Examples of humans overexploiting closed systems on earth can also be seen. For instance, although there is room for debate, it has long been generally assumed that Rapa Nui, the incredibly remote island in the middle of the Pacific Ocean (popularly known as Easter Island), was once rich in trees and was much more biodiverse. But then the island was deforested by the humans that eventually arrived there, possibly in order to facilitate the movement and construction of the giant stones used to create the mysterious heads that seem to have been part of the Islanders' self-expression as a civilization; meanwhile, the island's wildlife was overexploited, leading to a comparatively barren landscape today. For a balanced discussion, see Rethinking Easter Island’s Historic ‘Collapse’, but even if the eco-collapse scenario has been over-stated, the story it suggests is worth considering.

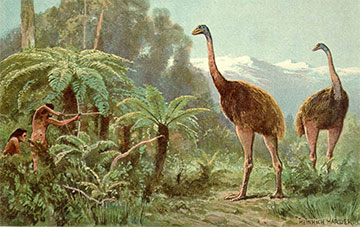

The moas, species of giant flightless birds that had lived in New Zealand for millions of years appear to have been hunted to extinction within 100 years of the arrival of human beings

When human beings arrived in New Zealand - which is assumed to have happened only about 700 years ago - the ecosystem of those islands began to be radically disrupted. New Zealand was probably largely wooded before man's arrival, and it had a large number of flightless bird species, because there were no land predators (so birds were safe to evolve into non-flying species) - until humans came. The arrival of human beings radically changed the biodiversity of New Zealand. As the Wikipedia article summarizes, "Since human arrival, almost half of the country's vertebrate species have become extinct, including at least fifty-one birds, three frogs, three lizards, one freshwater fish, and one bat." That's a lot of extinction to happen in 700 years.

Of course, humans still managed to live in New Zealand, and when the Europeans arrived, they brought a bunch of new species from Europe and other parts of the world as domesticated plants and animals. But if we think of Planet Earth as a much larger but finite island of this kind, we must realize that we Earthlings don't have anywhere else to get new species from to replace the ones we destroy ... We can't be sure what the overall effect on our enviroment will be if the mass extinctions caused by our activities continue, but there is good reason to think it will eventually be disastrous. We may have cattle to eat, but little fertile land to grow food for them, for instance.

Many thinkers are now recommending degrowth for the human race. This obviously goes against the imperatives of neoliberal capitalism (which equates success with economic growth). Along with degrowth, many environmentalists urge a redistribution of the resources our planet offers. For instance, in an excerpt from his provocative 2024 book Digital Degrowth: Technology in the Age of Survival, sociologist Michael Kwek blames the United States and American neoliberal capitalism (including America's "digital colonialism") for the environmental imbalance we currently find ourselves in:

There is enough to go around for everyone, but only if we spread it equally. ... If we want all 8 billion people to enjoy a decent standard of living that stays within planetary boundaries, we need to get rid of inequality between and within countries. The environment and human equality are fundamentally linked, and we need to stop treating people and nature like objects for self-gratification. (The Case for Digital Degrowth)

Rather than - or in collaboration with - radical economic and societal changes, could more technology now fix the problems that our technology has started to create for us as a species, and make a world and a human species that will be mutually supportive in the future? That sounds like the view of technology I decribed earlier in the course as techno-utopian.

This is one of Freeman Dyson's hopes, as explained in the reading. Humans have been screwing things up badly; more technology to the rescue! If we're putting forms of life at risk and some of them are going to disappear - well, we'll create new forms of life to fix things.

Biotech today

You are probably already aware of some common forms of biotech. If you have ever taken antibiotics, you were using a form of life that had been selected and probably modified by humans to fight against naturally occurring forms of microscopic life that can live in your system. You have probably also eaten many foods that come from genetically modified crops. Some people have been against genetic modification of food crops, and have requested that foods containing GMO (genetically modified organisms) be labelled. They worry that we don't really know enough about genetics to be sure that these modified forms of life are safe for us to consume, or safe for the rest of the environment, or they just don't think it is right for humans to be tinkering with nature like this.

Stacy's Pita Chips used to contain GMO grains, but have now been designated non-GMO

More radical and controversial examples of biotech are happening right now and coming soon. Goats have had gene sequences from spiders spliced into their developing embryos and it has led to a strange new kind of goat. No, the goats don't have eight legs and spin webs to trap humans, but they do have one thing naturally selected goats don't. Their milk contains a protein based on the one that spiders use to create their super-strong (for their size), super-light webs. Scientists hope to be able to extract this protein from the goats' milk and use it to create new fibres, perhaps stronger than anything humans have been able to create using non-living chemistry.

Humans have taken genes that make the poison in scorpion tails and spliced it into cabbage DNA. The hope is to create a cabbage that is harmless to humans, but poisonous to the slugs that often destroy cabbage crops. Genetic modification has led to a salmon that grows twice as fast as the naturally occuring variety. I'm not clear whether it has been determined if it's safe to eat, but the FDA approved the sale of the salmon in the U.S. in 2015. Foods from genetically modified plants have been allowed in the U.S. (and Canada) for a long time, but this was the first time a genetically modified animal was approved for sale.

A common hack is to make a plant (or animal!) glow in the dark (easy!). Here's a "fun" non-scientific video showing some other projects along these lines:

Both pigs and cows have been modified to make them release less harmful chemicals in their excrement.

These stories aren't bullshit. Lol.

There are more and more experiments with humans as well. For instance, in 2017 an attempt was made to "edit" a living man's genome. Brian Madeux, who suffers from a rare condition, had a version of his DNA that had the causes introduced into his system. In the end, this was not successful in treating his condition, but it did apparently harm him either. More recently, Victoria Gray, who has the inherited red blood condition known as Sickle Cell Disease - quite common among people of African American descent - had her condition successfully alleviated through gene therapy of this kind. So far these experiments are carried out on adults who can give their permission, but at least one attempt has been made to edit genes in unborn embryos. In 2018, the Chinese researcher defied medical ethics standards and Chinese law and attempted to edit the genetics of two twins who were not yet born. He was attempting to create resistance to HIV in the offspring. He was fired, tried, and sentenced to three years in prison. I have not been able to find out what happened to the twins and how they are doing today. There doesn't seem to be any information out there about their current wellness and whether they are resistant to HIV (one of the parents had HIV; this was part of He's experiment).

The hopes and the fears

There are a number of hopes and fears attached to the potential of biotechnology. Among the hopes are that this technology will end world hunger, help eradicate human diseases and disabilities, slow or modify human aging, perhaps even make us immortal, and ultimately allow us to create "improved" human beings (and other creatures).

Among the fears are that the technology will be weaponized or used for terrorism, that disastrous accidents may occur that have widespread consequences for humans or other species, or that the powerful may take control of the technology and use it to control or even modify the rest of us.

Another worry is the problematic idea of "eugenics." Eugenics is the idea that we can and should "improve" humanity and prevent certain people from reproducing their "inferior" genes. So far, those who have promoted eugenics have tended to have racist or other unquestioned biases. Who decides what is "superior" or an "improvement"? Who decides what is "inferior"? Quite apart from the human rights side of this question, it is impossible to fortell the future and be sure that what seems like a successful genome now will prove equally successful in the future. Those who understand species survival actually point out that more genetic diversity in a population will make the species more likely to survive whatever unforeseeable conditions may arise.

The creation of new species for a better world

While the fears people have about biotechnology being misused are entirely undestandable and should not be dismissed, there are lots of reasons to believe that this new "technology of life" will be a boon for a planet struggling with overpopulation and climate upheaval. New species dreamt-up by humans could make the world a better place (at least for human beings).

Freeman Dyson, the author of this week's reading, explains - for instance - how plants with black leaves made of silicon would absorb the sun’s energy much better than plants with green leaves. If we could bioengineer such plants, we might have an efficient living tool for capturing solar energy. Dyson assumes that biotech will give us many new "tools" for improving our lives. Unlike the machines we have for tools now, these new tools will be alive.

After we have explored this route to the end, when we have created new forests of black-leaved plants that can use sunlight ten times more efficiently than natural plants, we shall be confronted by a new set of environmental problems. Who shall be allowed to grow the black-leaved plants? Will black-leaved plants remain an artificially maintained cultivar, or will they invade and permanently change the natural ecology? What shall we do with the silicon trash that these plants leave behind them? Shall we be able to design a whole ecology of silicon-eating microbes and fungi and earthworms to keep the black-leaved plants in balance with the rest of nature and to recycle their silicon? The twenty-first century will bring us powerful new tools of genetic engineering with which to manipulate our farms and forests. With the new tools will come new questions and new responsibilities. (Dyson, p. 5)

The Domestication of Biotechnology

Dyson believes that when the science and technology of biotech come of age, it will be shared by all of us ordinary citizens who will engage in our own biological engineering for the good of the human species. His model for this is what happened with computers and the Internet, which went from being available only to scientists, government, and big business to being something that all of us use every day.

I predict that the domestication of biotechnology will dominate our lives during the next fifty years at least as much as the domestication of computers has dominated our lives during the previous fifty years. (Dyson, p. 1)

In other words, just as computers went from being at the command only of scientists, corporations, and governments to become something practically everyone has, so biotechnology will be something the average person has access to in this new century.

Domesticated biotechnology, once it gets into the hands of housewives and children, will give us an explosion of diversity of new living creatures, rather than the monoculture crops that the big corporations prefer. New lineages will proliferate to replace those that monoculture farming and deforestation have destroyed. Designing genomes will be a personal thing, a new art form as creative as painting or sculpture. (Dyson, p. 2)

In the reading, Dyson distinguishes between what he calls "green technology" (not to be confused with environmentally friendly technology) and "gray technology." Green technology was how humanity started (agriculture and selective breeding of livestock); gray technology is the kind of thing you are more likely to think of if you think of technology in our present-day terms: machines, steel, computers. Green tech is the shaping and use of living beings for human good; grey technology is the shaping and use of non-living matter (stone tools, the wheel, metal weapons and tools, machinery, computers).

Gray technology is the technology that gave birth to cities and empires five thousand years later, starting from the forging of bronze and iron, the invention of wheeled vehicles and paved roads, the building of ships and war chariots, the manufacture of swords and guns and bombs. Gray technology also produced the steel plows, tractors, reapers, and processing plants that made agriculture more productive and transferred much of the resulting wealth from village-based farmers to city-based corporations. (Dyson p. 6)

Dyson hopes that a return to a sophisticated version of green technology will be a boon for the poor people on this planet, who have little access to gray technology.

If rural poverty is a consequence of the unbalanced growth of gray technology, it is possible that a shift in the balance back from gray to green might cause rural poverty to disappear. That is my dream. During the last fifty years we have seen explosive progress in the scientific understanding of the basic processes of life, and in the last twenty years this new understanding has given rise to explosive growth of green technology. The new green technology allows us to breed new varieties of animals and plants as our ancestors did ten thousand years ago, but now a hundred times faster. (Dyson p. 6)

Why "domesticate" biotech?

Though the idea of "domesticating" such a powerful form of technology - making it available to "home users" - will probably sound terrifying to most people, Dyson does have several legitimate arguments for why that would be the best thing to do. I will summarize some of his arguments here and add to them where I can.

Fairness and equity

It is fairer and safer to have powerful technology in the hands of everyone than in the hands only of the rich, the government, or the corporations. Life is the inheritance of us all, and if anyone is going to change it, we all should have that right. This argument bears some similarity to arguments that have been made about universal "environmental rights." Since all humans have to live with the impacts, shouldn't all humans have a say in what is done?

More freely competive

Domestication would make for a level playing field, allowing ordinary people to compete with giant corporations, and subsistence farmers to engineer forms of crops and livestock that will be adapted to their changing environmental circumstances. Climate change is on Dyson's radar, and he imagines that biotech may allow us to create forms of life that can cope with hotter and drier climates. He seems to be coming from a libertarian ideological perspective, and to assume that more competition is better and that an entrenched government or large monopolistic corporations will not be in the position to do the best work with the new technology. Ordinary people will be more likely to do what is needed.

Greater diversity of "products"

With so many more humans playing around with biochemistry, there will be an explosion in new life forms, many of which will be beneficial to humanity. Corporations will only be focused on things that can make money; individuals may be more focused on things that they care about for their own sakes, things that are probably better for us and the world.

Better understanding and more appreciation of life

Having everyone understand and use biotech will bring us back into contact with the reality that humans are part of life ("all my relations") and give all of us a more profound understanding of what life is. As we take over the control of life, we will also appreciate that life is us and we are life, and we will return our focus to what is real and really matters for us animals, and turn away from the dead mechanical false world to which we are currently attached.

Hard questions

Freeman Dyson was already in his eighties when he wrote this article. He passed away in February 2020. Dyson admits that his idea of biotech for everybody raises hard questions, but he leaves those to be answered by future generations:

If domestication of biotechnology is the wave of the future, five important questions need to be answered. First, can it be stopped? Second, ought it to be stopped? Third, if stopping it is either impossible or undesirable, what are the appropriate limits that our society must impose on it? Fourth, how should the limits be decided? Fifth, how should the limits be enforced, nationally and internationally? I do not attempt to answer these questions here. I leave it to our children and grandchildren to supply the answers. (Dyson, p. 2)

Does his offloading of responsibility at the end piss you off? Some would argue that we urgently need to ask all these questions right now, before we take any further steps down that path. Anyone hearing about all this for the first time might well think: we should stop this research right now! Whether it seems sacrilegious or merely foolhardy, humans aren't ready to take on the godlike role of changing how life works on this planet. When I first started teaching this article, this seemed to be most people's reaction.

Dyson's second question is whether we should stop this "wave of the future." This is a good question.

Many people, including me (and most of the smartest scientists), are not convinced that even the smartest scientists today understand the web of interrelation of species well enough to know what the results of changing it will be. It's seems likely to me that we don't know enough about the web of life yet to start modifying it in radical ways, and that we can expect many unintended consequences of our modifying it. Some of these could turn out to be disastrous.

Imagine, for instance, if the change made to the DNA of the spider goats so they would produce spider silk protein in their milk also had an unrelated impact on some aspect of their urine. The modified urine in turn has impact on plants the goats pee on, the plants are eaten by insects, etc etc. This is probably not a very scientific scenario, but it quickly illustrates why someone might worry.

The benefits may be too great to resist, though. I wouldn't be at all surprised if some of you lived to enjoy benefits from biotechnology that would make you glad we had continued with it. Maybe it will eradicate cancer, prolong all our lives, solve global warming or global hunger. It seems creepy and dangerous, but is it actually going to be mostly a positive thing? I hope so, and hope some day you will look back on this lesson and smile. (Boy, that lesson really got me worrying for a bit, but you wouldn't even be here today if it weren't for biotech! [kisses artificially youthful and non-cancerous partner, child, or parent.]

The third, fourth, and fifth questions are perhaps the hardest. I'll turn to them in a moment. But let's start with some arguments that we shouldn't be doing this at all. Presumably, if enough people believed that we should stop, we could stop.

Are humans ready for this power, as individuals, as nations, as a species?

I will leave aside religious questions about whether "Man should play at being God" and also the question I just raised about whether the science is there yet to do this safely (or if it ever will be), and move directly to the more basic question: is the human species emotionally and morally mature enough to have and use this power? Donald Trump's presidency, for example, suggests the opposite to me.

In an article he had written earlier - "Can science be ethical?" - Freeman Dyson had asked whether science was strictly an impersonal pursuit of pure knowledge or whether it could/should be done in a way that included moral guiding principles. He worried that humanity has not progressed morally at the same pace as it has progressed technologically:

scientists and entrepreneurs must assert their freedom to promote new technologies that are more friendly than the old to poor people and poor countries. The ethical standards of scientists must change as the scope of the good and evil caused by science has changed. In the long run, as Haldane and Einstein said, ethical progress is the only cure for the damage done by scientific progress.” (The New York Review, April 19, 1997)

As you can see, just as in the biotech article for this week, Dyson is concerned about the poor people of the world, and worries that science is in the hands and serves the interests of the rich. But his final point echoes what Einstein said after they dropped the atomic bomb: "It has become appallingly obvious that our technology has exceeded our humanity." Another famous scientist, the biologist Edward O. Wilson, once put it this way: "The real problem of humanity is the

following: we have

Paleolithic emotions,

medieval institutions,

and godlike technology ." In other words, we still have the emotions of savages or animals, we live according to outdated social models, but we have tremendous technological power. Can we mature ethically - in terms of self-control, reflection, compassion, and selflessness - so as not to make our technological power a disastrous nightmare for each other, the rest of life on eart, and ourselves?

For me, the question behind all this, the really interesting and crucial question, is Can we grow up? – to use the power of technology at our fingertips for the good of all humans and the planet, rather than short-term personal gain, power-strutting, or wanton cruelty to others?

Can we be trusted? - as a species - to take care of ourselves and the rest of the life on this planet in a thoughtful and compassionate way? It's hard to imagine that too many of you reading this are silently affirming "Yes!" right now.

We're at a really interesting point in the history of the human race. The species is acting on a global scale, and things seem pretty risky. If the human species were a character in a book, we'd be at the major plot crisis. Is the character going to get it together and do the right thing, grow, change, become responsible? Or is this going to be a story of self-destructive excess, ultimately a tragedy.

Non-human rights

A question Dyson doesn't actually mention, but one that some people will have front and centre in their minds, I think, is whether animals or other lifeforms should have "rights," especially if they have been engineered by us and include human elements as well as non-human ones. I think Dyson sees animals as just "resources" for humans to use, but many people today are concerned about animal cruelty, and some have even proposed that "personhood" should be granted to some of our more intelligent cousins (dolphins, whales, chimps, maybe even octupi!) or to animals we live with, who support us and who trust us and rely on us for support (dogs, cats, etc). Again, a more indigenous perspective, I think, would see the animals as equals, our relatives, and not there for us to abuse and disrespect in these manipulative kinds of ways.

Among the things we will likely see soon are animals modified so that they can internally grow replacement organs for humans who need them. Patricia Piccinini's 2004 art work The Young Family dramatizes this.

Does humanity owe anything to the rest of life on earth? Do we have any responsibilities to it? If we destroy the rain forest or make species go extinct through climate change, or start messing with the internal workings of animals for our own interests, are we turning on our "relations," betraying our kin, and also nullifying any possible moral excuse for thinking we should be the boss of life? If there is no God, there is no one to say we shouldn't do as we like, but some humans themselves feel it is simply wrong to treat other species like this. In the meantime, the abuse of other species goes on constantly, with most of us barely aware of it (factory farming of animals, experimentation, etc).

What part of humanity should control this new power?

Finally, we come to the last of Dyson's "rhetorical" questions. Assuming this power is coming - and fast - who do we think should decide what we do with this technology?

Dyson argues - for reasons that I can understand - that every human being has a right to this technology and that ultimately that will be good for the world. Powerful technology is a HUMAN RIGHTS issue. Imagine if only the government and corporate CEOs had computers today. But that technology is in all of our hands, at least to some extent. And on the whole, I would say, we are doing better things with it than the government or corporations often are.

If you don't think ordinary citizens should ever be given power like this, who should decide what is done and isn't done with the technology of life?

This draws attention to a painful problem. Your choices are limited. Who do you trust (the most)?

- the government

- scientists and academics

- corporations

- your fellow citizens

You can say "nobody," but that doesn't change the fact that the technology is on its way. If you really believe we should stop exploring biotechnology right now (and I can understand why you might), you should be out demonstrating and getting together petitions, and asking for Canada to take it to the U.N. - a moratorium on all biotech development. Otherwise, you have to decide how you think the technology should be controlled - unless you don't think there is any need to control it.

Who do you trust the most? I find it hard to answer that question myself, but I can tell you who I don't trust: the corporations. They have already shown that they don't consider human rights or environmental rights to be as important as their bottom line (which is understandable: their aim is to make profit; everything else is treated as "an externality," as Suzuki and Moola put it). I feel like the only power strong enough to keep the corporations in line is the government (I'm just thinking of the Canadian government here), and so - as with global warming - it seems to me that the government should probably be monitoring and regulating the research and implementation of biotech, carefully and heavily. But I can see why others might argue differently. (You will have a chance to make your own provisional decision in this week's tie-in exercise.)

Ultimately, as with climate change, this new technology makes it painfully obvious to me how much we need a global governing body and a world perspective on issues that affect the entirety of humankind. It doesn't do enough if Canada regulates biotech and reduces carbon emissions; the whole world has to somehow come together and agree, and then hold people accountable who try to step out of line.

It sounds utterly far-fetched, yet it may be our only hope. I think we have to try to make this happen.

This also may demand an abandonment, by the way, of the belief that human beings are naturally competitive and that competition is good for everyone. I really believe that we humans need to tap into our naturally cooperative side again, desperately.

The superhuman of the future

Humans have created many kinds of god, and I'm not sure how totally good any of them have been. If we are going to play god ourselves with the other species of this world, create new species, and ultimately reshape ourselves, what image do we have for the superhuman of the future?

Generally when people think of these questions they have the most selfish and superficial kinds of ideas. We should make people blond (white suprematist), make them taller, give them more beautiful bodies, bigger breasts, larger penises, plumper lips and darker eyebrows, or whatever is in fashion right now. Definitely make them stronger, more powerful, more dangerous, smarter. Genetics and cyborg technology hold out these possibilities realistically for the near future - at least for the privileged.

Workaholic monkeys

What about the rest of us? I was alarmed to read of a study that was being done in 2004 on monkeys, our primate cousins.

Like many humans, monkeys tend to slack off when their goal is distant, then work harder as a deadline looms. But when a key gene is turned off, the primates work hard from the word go, researchers report in PNAS Online1. "The gene knockdown triggered a remarkable transformation in the simian work ethic," says Barry Richmond of the National Institute of Mental Health in Bethesda, Maryland, who studied the animals.

With the gene turned off, the monkeys were unable to anticipate how many trials were left before the reward was given. They stopped procrastinating and worked hard throughout the task, making consistently fewer errors at every stage. The monkeys became extreme workaholics ... This was conspicuously out-of-character for these animals. (Helen Pilcher, "Gene therapy cures laziness in monkeys," Nature, Aug 11, 2004)

I have to wonder what the purpose of such research was. Note that they weren't trying to find out what made monkeys happier, or more creative, or kinder, or more compassionate, or more able to enjoy sensual pleasures, or even smarter. They were trying to find out what would make them work harder.

In Aldous Huxley's SF novel Brave New World (1932), humans are born and bred to be in one of a few different classes or castes. A combination of embryo therapy and conditioning is used to make every person, regardless of their class, happy with their lot in life.

Presumably someone in 2004 thought it would be useful to know how genetic engineering can make primates more "productive" - the capitalist value par execellence. I'm not at all a conspiracy theorist, but I do still wonder who funded that research ...

My own proposals for the genetically modified human of the future

Assuming we do get to the point where we can improve humans through genetic engineering, here are some of my suggestions for how we change ourseleves:

Make a human who is better adapted to living in the world we live in.

Such a human would be rid of many of the instincts that kept us alive when we were struggling for survival on the African savannah 50,000 years ago, where food was scarce, etc. We could reduce our appetites for sugar, fat, and protein, since most of us consume too much of those things now, as they are no longer scarce. We crave them because they were once hard to get.

We could make our metabolisms more able to process food efficiently. We should reduce our tendencies to aggression and competition and increase our senses of empathy and cooperation. Perhaps the testosterone should be cut. "Alpha Males" aren't doing anybody any good these days, not even themselves.

Increase intelligence and decrease anxiety. Increase life span? Assuming we have found ways of feeding everyone on earth without wrecking the environment. If not, perhaps decrease mating fertility, so fewer babies are born, especially unintended ones.

Ultimately, I'm recommending that we genetically engineer not stronger, bigger, more "master race" white (or black) supermonsters. What we need now are healthier, better adapted, more peaceful, more compassionate creatures. Buddhist monks, Native American respecters of life. Wise grown ups.

Natural selection would be unlikely to favour such creatures; but artificial selection could ...

Biotechnology. The next big thing.

The power is coming – fast! It's an exciting point in the story of our species. How will the story turn out?

Are we going to grow up?

The future is not written.

We are writing it now.