WEEK 08: You are political

Be sure you understand

- ideology

- left and right

- authoritarian and libertarian

- socialist - liberal - conservative

GNED 101 starts with questions that are more personal or abstract - what is reality? do you care if you are in touch with it? - and then moves out from the individual to a more social context: how does society and interaction with other people shape who we are? Unit Three moves into a much larger context: the national and global sphere. Many people will feel that these questions are too large for them to consider or participate in (what should government be like? how can we save the planet? should technology be controlled, and if so how?). But ultimately it is human beings who must decide these questions, and you are one of them. Since we live in a democracy, with elected representatives and free speech, your response to these massive issues is part of Canada's response, and by extension part of humanity's.

We start by taking a look at politics. There are two kinds of people in the world: those who don't want to talk about politics at all and those who want to talk about politics too much. ;-) Whichever you are, I hope you will continue reading and open your mind to thinking more about some basic concepts that are used in discussing politics in democratic countries like Canada.

For this lesson, we focus on a few key political terms and encourage you to understand them more deeply and try to situate yourself politically, if you have never done so before, or think about your position and how it fits into the political spectrum. The terms and concepts you need to understand are

- ideology

- left and right

- authoritarian and libertarian

- socialist - liberal - conservative

We’ll be using a popular web tool – The Political Compass – that is almost like a Buzzfeed quiz, and I'll use a couple of diagrams that try to help you visualize and analyse the political spectrum. The tools, definitions, and graphs no doubt all have their own political biases, though they are trying to be neutral. I make an attempt not to be too biased in my presentation, but of course I have my own political attitudes, and they will no doubt colour how I present the material. That’s one of the most important points in the reading by Aileen Herman: everyone has a political position, even if they don’t know what it is and consider themselves “apolitical.” Politics is about power, especially the power of governments and authorities, and how you think it should be used. “I’m not political” is not really a meaningful statement. It just means you don’t want to acknowledge or think about or discuss your politics. Or you may not even know what they are. This lesson is meant to be a step in that direction. For some it may seem simple-minded and elementary; for others it will be largely or framed in a different way that can give you something to think about, argue with, or memorize and then forget, as you see fit.

Some of you may already be very aware of where you stand politically. But often people - especially young people who have so far been little involved in the democratic proces - think they "don't have any politics." Particularly if that is your case, read on!

If you don’t care about politics, it’s because you don’t have any political problems

When you talk to Canadians, many of them will say they are not interested in politics. Though we have higher voter turnout than the United States, 1/3 or more of eligible Canadian voters have not voted in a Federal election during the last 20 years. Others have voted in careless ways (whoever their family and friends vote for, whatever candidate they like the look of best, whoever's ads they found more compelling, whoever they believe will make or save money for them personally).

The reasons people don't vote will be familiar: they find politics “boring” (it can be!); they think all politicians are dishonest (most of them probably are); they don’t think it will make a difference because government does whatever it wants anyway (I don’t think this is true); they don’t think it really matters who is in power (I don’t think this is true either). This lesson will invite you to think more about those assumptions, if you have some or all of them.

I think one reason so many people don’t care about politics in Canada is that most of us don’t have to. Our government does not persecute most of us, we have lots of freedoms and our human rights are mostly well protected. At the same time, it may be hard to see government and political policies as directly affecting the parts of our lives that are important to us. Many Canadians have only two "political" issues that they feel they need to worry about: how high their taxes are and whether they have a job. People have gotten used to thinking that the only thing political candidates can do for them (or society, or the world) is affect their personal finances. In Canada, as people have started to say, a lot of us have the privilege of not having to care about politics.

Of course, the further away you are from the most privileged positions in society, the more you may take an active interest in politics. If you are a woman, you may be “more politicized” than a man. If you are a person of colour you may be more attunded to politics than a white person. If you are queer, poor, indigenous, disabled, Muslim, or some other kind of person who has been marginalized or targeted in Canadian society, you may well also be more interested in politics. Politics is more than just electing representatives. Politics is about power. Herman quotes Harold Lasswell’s definition of politics with approval in the reading for this week: politics is about “who gets what, when and how.”

The banality of politics

In the reading, Herman shows how everything we do actually has a political dimension to it. When we buy a cup of coffee, whether we know it or not, we are acting politically. If the coffee you buy is “Fair Trade” (as all coffee sold on campus at Humber must now be), you can assume that more of your money is going back into the people who grow the coffee, in another part of the world, where – for the most part – poverty is common and there are fewer workers’ rights than in Canada. As you will see, Fair Trade coffee is "left-wing" coffee.

Fair Trade seeks to improve the lives of coffee farmers and producers of other coveted products such as cocoa, bananas, crafts and textiles, by offering consumers an ethical alternative to mainstream trade networks. In particular, Fair Trade certification indicates that the relationship between producers and buyers is direct, that producers are earning a “living wage" and that a percentage of the earnings goes toward grassroots community development (Fairtrade Foundation, 2018, qtd in Herman).

Buying Fair Trade products is a small political action you can take to show support for exploited workers in other countries.

If you prefer coffee from somewhere that is not Fair Trade, and pick one up there on the way to campus, that was in a sense a political act, even though it is not a conscious one, and there may be no political intention in your choice. You may have unconsciously chosen to support a company and a system that exploits people in another part of the world, so that you can have good, inexpensive coffee here. This suggests a more "right-wing" attitude toward coffee. Some people are comparatively poor (most coffee farmers in Guatemala, for instance, where Herman did a field placement) and some are comparatively rich (you, by global standards). That is not your fault or your problem, and you don't expect the Canadian government to do anything about it either.

For many people the only question here is, how much does the good coffee cost me. Focusing on that aspect of the coffee alone is also a political attitude.

The ideological spectrum

Ideology is a fancy word for a bunch of values and assumptions that tie together to represent an attitude about the world. Everyone operates according to certain ideologies, even if they never consciously think about their values and beliefs and don't have a name for them.

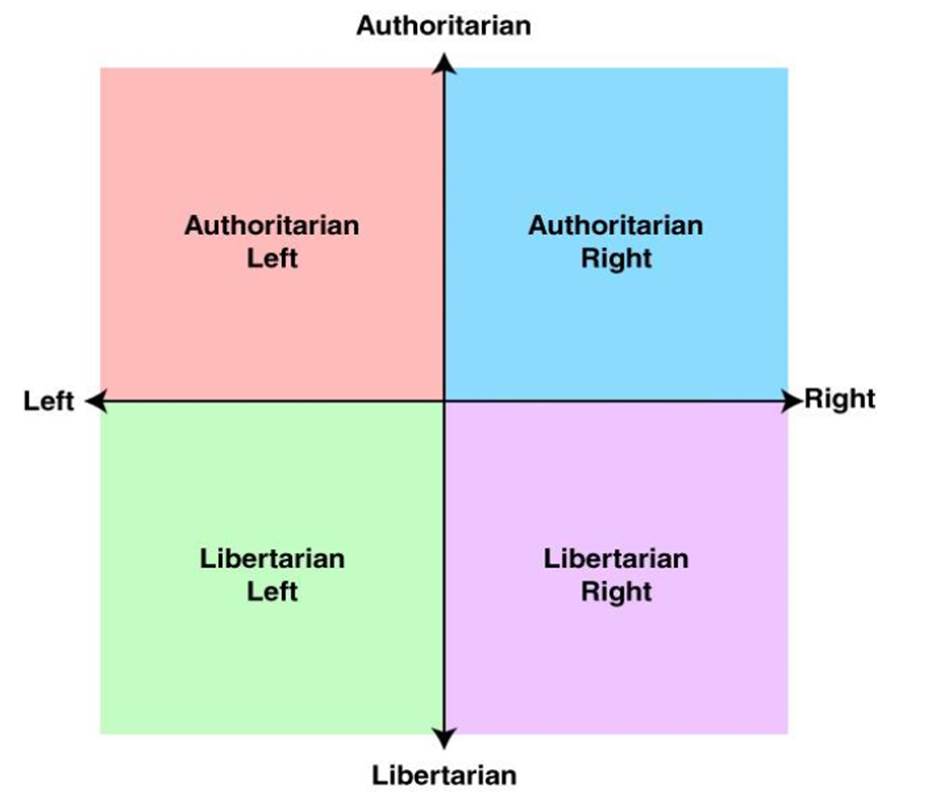

The website you will use to get a reading on you political ideologies is called The Political Compass. It divides up political ideology according to the two most common axes of political division in the Western world: left vs right, and authoritarian vs libertarian.

It’s not clear what the political bias of the Compass site itself is, but it has been popular with people from many political backgrounds (though sometimes criticized for being biased or too simplistic to provide useful guidance). The site asks you a series of questions and from your answers it calculates where on the political spectrum you are.

Your assignment this week is to go through the Political Compass questionnaire, save your results, and then think about them, at least briefly. You might want to go do the questionnaire now, do the exercise, and then continue reading. (Click here for the instructions if you want to complete the Compass before continuing.)

The Compass tool seems to originate in Great Britain, but it is pretty focused on the United States political scene, as a lot of political debate tends to be in the Western world, especially now. It works pretty well for Canada, however, which often reflects or comes close to aspects of the American political scene, and practices a somewhat similar form of democracy.

The Political Compass divides up the political spectrum according to two of the ways there is the most difference of opinion about how government should relate to its citizens. One axis is LEFT vs RIGHT, which is the question about how much the government should interfere to try to help make people more equal, especially in terms of economics. The other axis is AUTHORITARIAN vs LIBERTARIAN, which is about how much control the government should have of an individual citizen's behaviour and actions - what should be legal and illegal, how much power the government should have over individual freedom.

For instance, your attitude about socialized medicine will put you somewhere along the LEFT-RIGHT spectrum (should all people have access to free health care? should the rich be able to pay for a higher standard of health care?). On the other hand, your attitude about whether gay people should be able to get legally married will put you somewhere along the AUTHORITARIAN-LIBERTARIAN spectrum.

In a contemporary North American context, the LEFT-RIGHT arguments are most often about money (taxes, government spending, minimum wage, corporate profits) and the AUTHORITARIAN-LIBERTARIAN arguments are often about social conventions and what should be allowed for the sake of safety and morality (things like trans rights, abortion, hate speech, legalization of marijuana, legalization of sex work, etc).

The Compass divides up political ideologies into four quadrants. After you do the Compass exercise, you will be told in which quadrant the tool thinks you land. You may be surprised to see where you land, and you might think the Compass got it wrong. But it’s worth considering what your answers to those questions seem to suggest about your current political position.

The Left - Right Axis

The Left-Right axis suggests how you feel about the principle of egalitarianism. Should people all have the same basic wealth and opportunities, and should the government do things to make that more of a reality? The further to the left you are, the more you are interested in sharing the wealth and protecting or even promoting everyone equally. The further to the right you are, the greater your tolerance for socioeconomic diversity and inequalities.

The three most common political ideologies in the democratic world today are probably socialism, liberalism, and conservativism. (Rarer and less frequent are governments where forms of monarchy and aristocracy are still being practiced. In other cases, it isn’t easy to describe the situation with these terms. For instance, China still operates in part as a “communist” (or at least socialist) state, but also has an emerging capitalist middle class that likely operates more along the lines of Conservatism. The government is not a democracry but a totalitarianism and enforces “equality” on some members of society while allowing others to operate more freely, up to a point. In the terms of the other axis, to be discussed in a moment, that government is very authoritarian.)

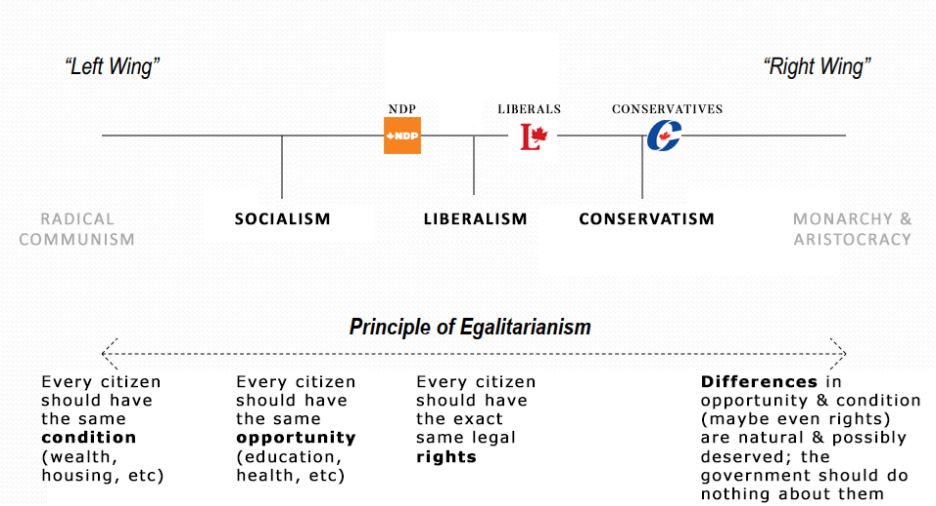

Canada generally wavers between conservatism and liberalism, with occasional local moves in the direction of socialism (the NDP, though it is not a "socialist" party; leans in the direction of what Bernie Sanders called his platform: "social democracy").

Socialism is to the left, liberalism is in the middle, and conservatism is on the right hand side.

These are potentially confusing terms, as two of these abstract ideologies are also the names of political parties in Canada. Here we’re talking about socialism, liberalism, and conservatism as abstract ideologies. Not the names of current parties. See the diagram below, where the approximate position of the NDP and Canadian Liberal and Conservative parties are shown on the abstract spectrum of ideologies.

In addition, the term "Conservative" is not only used for questions of economic equality. It can also be an attitude toward social and “moral” issues. One can be “fiscally conservative” (on the Right in terms of economics) and “socially progressive” (support queer rights etc). Or vice versa. Conservative parties in both Canada and the United States often appeal both to people who are fiscally conservative and to people who are socially conservative. There is also often a combination on the Left of socially progressive attitudes with an interest in improving opportunities for those who are underprivileged.

At the extreme left of this axis would be a pure communist state in which absolutely every citizen had exactly the same standard of living, rights, and conditions of life. At the extreme right would be a state where various classes or castes had different rights and opportunities, and there was extreme inequality in wealth and living conditions.

One of the ideals of classical liberal democracy (the philosophy on which Britain, Canada, and the United States are founded) is that every citizen has the same rights. In principle, if not in practice, this means that you have the same rights whether you are a man or a woman, whatever your race, and so on. The idea of freedom with equal rights is at the centre of this left-right distribution. Few socialists or conservatives are likely to say that we shouldn't all have equal rights, but they may disagree about how that should be interpreted. A major question is whether, given that we are all born with different advantages and positions in society, and there are problems like racism and sexism that are not strictly rectified by formal legal rights, the government should work to give all its citizens more equal opportunities, not just equal rights in the strict sense. On the whole, the further left you are the more you want the government to do that, and the further right you are the less you think the government should be involved in making citizens more "artificially" equal.

The authoritarian-libertarian axis

The other axis has to do with how much control of an individual citizen the government should have.

Those who distrust government or think it is unnecessary are closer to the bottom, libertarianism. The extreme form of the libertarian view is anarchism, the belief that having no government is best.

Libertarianism on the left might be exemplified by the anarcho-communist ideals of Karl Marx (not the governments that have claimed to be "Marxist" such as the Soviet Union and China), where power would be decentralized and small communes would practice self-governance with collective ownership of resources, land, and property.

Libertarianism on the right suggests individuals or groups who have opted out of democratic action, perhaps forming their own private militias, organized crime syndicates, or other self-interested allegiances, believing government has little to offer them and constrains their natural freedoms.

On the top half is the opposite extreme: authoritarianism, the belief that the government needs to keep citizens in line. The extremest form is fascism or totalitarianism, where the powerful people who run the government keep many or most citizens under control in what amounts to a police state, with pervasive surveillance, severe penalties for those who don't comply, no rights to public trial, or corrupt double-standards for those with privilege and influence.

Josef Stalin (left) and Adolf Hitler (right) - two leaders of notoriously authoritarian governments in the 20th century.

Authoritarianism on the left at its most radical could perhaps be exemplifed by the People's Republic of China during its early years, or Stalinist Russia (in principle at least): a strong state makes sure that every citizen has a similar quality of life and controls any attempts at creating non-state-sanctioned privilege. Of course, there was much internal abuse and privilege still operating in these countries, but that was their stated doctrine at least.

Extreme authoritarianism on the right suggests Nazi Germany, with its clear racist policies of white supremacy and control of the population through fear, policing, and propaganda. Privilege based on birth was not just accepted, it became the model of a hierarchical society in which the "Aryan" white people were on top and others were excluded to the point of expulsion and eventually murder. Power was centralized in the government's leadership and enforced on the population with policing, informers, surveillance, and other tools of fear.

If you think the government should have little say in what an individual does (as long as they aren't hurting someone else) you're more libertarian. If you think the government should dictate individual behaviour (usually for a "moral" reason, or an "ideal" such as fundamentalist religious values or white supremacism) you are more authoritarian.

For instance, should there be laws around a "victimless" crime like gambling? The more libertarian you are, the more you would probably think gambling should be available to anyone regardless of age, anywhere, at any time. The more authoritarian you are, the more you probably think there should be limits, or perhaps it should be outlawed altogther.

Similarly with matters such as sex work, abortion, age of consent, and other questions that people may associate with morality. Former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau (Justin's more famous father) once said "There's no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation." This expresses a libertarian attitude: what consenting adults do in terms of sex is not a matter for legislation. You can contrast this attitude with the authoritarian policies of governments like Yemen, Iran, Singapore, Brunei, or many nations in Africa where homosexuality is illegal. In the most extreme cases, it can be punishable by death.

This video by popular YouTuber jreg - though it should obviously not be taken too seriously or used for study purposes! - provides a more entertaining caricature of how people in each quadrant may be seen by those in the other quadrants.

These are caricatures, and I would say that Jreg himself is coming from the bottom left quadrant, so the characterizations should be taken with a grain of salt.

The Political Compass focuses on the two axes of left-right and authoritarian-libertarian, but obviously politics and any individual's personal ideology are not so simple. Important dimensions are left out. For instance, the range of social attitudes between conservative and progressive are not really identical to either of the two axes. As I briefly mentioned, there are really two kinds of conservativism: fiscal conservatism, which focuses on the government not being involved in the capitalist economy, not regulating personal wealth, not taxing the wealthy to support the poor or changing the rules of trade etc, and social conservatism, which focuses on issues some people would define as "moral." Social conservatism wishes to resist changes in social mores, and for the government to make certain social behaviours illegal or underprivileged for the safety and good of those practising "more traditional" lifestyles. The conservative parties in the U.S. and Canada atttract both kinds of conservatives, but it is possible to be socially progressive and fiscally conservative, or vice versa.

Similarly, someone like me, who gets categorized as both left and libertarian, can be quite happy to have the government become authoritarian when it comes to regulating the extremes of wealth distribution (I lean in the direction of "Democratic Socialism"), though libertarian when it comes to the social issues (pro-LGBT, anti-racist, etc). So maybe I am a "fiscal authoritarian" but a "social libertarian." In the popular media, there tends to be an assumption that in the United States and Canada, further left means bigger government, and this is why it seems strange to see the NDP in a libertarian quadrant (and myself even deeper there) and the Conservatives way up in the authoritarian quadrant. So this may be more a reflection of those parties' attitudes toward legislative attitudes toward social issues: eg, drugs, sex work, abortion, LGBTQ rights, and so forth.

Things are more complex than these two axes, and the Political Compass questionnaire is not a scientific tool providing refined analysis. The little tool provides a basic impression of a person's ideology that people who study politics more seriously will find simplistic and potentially misleading, but it does at least begin to situate you within the most common political debates and attitudes in Canada today. Every time I've taken it, it has landed me in the Left Libertarian quadrant, and that feels right to me, and reflects my own party affiliations.

I hope you learn something about yourself and your world by exploring it.