Approaches to anxiety

Be sure you understand

- The Psychoanalytical (or Freudian) approach (theory of causes and methods of treatment)

- Id, Ego, and Superego; Repression and the Return of the Repressed

- The Behaviourist approach (theory of causes and methods of treatment)

- Gradual exposure re-conditioning

- The Cognitive approach (theory of causes and methods of treatment)

- The Neurological approach (theory of causes and methods of treatment)

You might find it useful to download this study sheet and fill it in as you read to faciliate remembering these ideas accurately for testing.

Although I talk about a lot of different approaches and ideas about anxiety here, the focus of testing will be a clear understanding of the differences and simularities or intersections between the four approaches listed above. That is the part you should study and understand. The rest is provided mainly for those who may suffer from anxiety, as additional information.

ORIGINAL BASIS OF THIS READING (for comparison and background)

[Some of this has been adapted from the official online lesson, which my lesson replaces. Unless otherwise indicated, quotations are from the reading by Freeman and Freeman. I've made that reading optional. If you are interested in this topic, it’s well worth reading what they have to say to get a fuller understanding of what I’ll talk about here.]

if you would like to talk to someone about mental health struggles, a good place to start is Humber's free confidential counselling services.

This lesson looks at four different approaches to the problem of anxiety as a psychological disorder: the Freudian approach, the Behaviourist approach, the Cognitive approach, and the Neurobiological approach.

This lesson looks at four different approaches to the problem of anxiety as a psychological disorder: the Freudian approach, the Behaviourist approach, the Cognitive approach, and the Neurobiological approach.

I personally have suffered from anxiety at various times in my life and can still experience episodes at times. During the pandemic lockdown of Winter 2020/2021 I started experiencing severe anxiety episodes again, after many years of relative calm. I have tried treatments related to all of the approaches discussed here. Personally, I've found each to have some things to be said for it.

The most common and successful way of dealing with serious and chronic anxiety right now combines aspects of Cognitive Therapy (the cognitive approach) and drug therapy (the neurobiological approach). I think there is something to be learned from the other two approaches as well, and I have also found a fifth approach, mindfulness and meditation, to be helpful at times, so I will mention that at the end of this lesson. Exercise is also beneficial, and emerging therapies such as vagus nerve stimulation, which is already used for some cases of depression and epilepsy, may prove helpful for anxiety as well.

Many people today suffer from bouts of anxiety and depression. I polled my GNED class anonymously last year and 70% reported they had suffered from serious anxiety at some point, or were suffering from it now!

If you think you may be suffering from acute or chronic anxiety (or other conditions, such as depression), I strongly encourage you to get professional help in the form of psychotherapy/counselling. A good place to begin is Humber's free Student Wellness Centre, which offers both health and counselling services. I have not used their counselling services myself (you have to be a student), but I have heard good things about them. I found my current therapist, who is excellent, through the Ontario Psychotherapy and Counselling referral program, which connects people with therapists who in many cases charge on a sliding scale depending on what you can pay. An ex-partner of mine also found a superior therapist through that service. Don't hesitate to contact me if you are thinking about it and have questions or concerns.

Anxiety: A normal response to danger and self-preservation

In the reading, Daniel and Jason Freeman point out that anxiety is a natural emotion, and in many respects we actually need anxiety—it is crucial to our survival. Anxiety “orients us to danger and prepares our bodies to either challenge or escape it.”

Like other animals, humans constantly evaluate their environment for cues about what they need or desire or should protect themselves from. Our initial appraisal or interpretation of any situation may not be a conscious process, but may be more of an “intuition.” It is as if our senses function like an “early warning system” picking up on what may be important and passing this information on to the more rational and deliberate parts of our brains to ponder or consider. When we perceive or sense a threat we are not sure we can handle, or we’re uncertain of how to handle it, or we're too afraid to handle it, then we feel anxiety.

Anxiety can be felt in real life situations where we are hesitating between the commonest responses to danger: fight, flight, or freeze. If we are not sure we have done enough or the right thing to protect ourselves, the anxiety can kick in to force us to double-check. It is a normal experience to feel temporariIy anxious. You have probably felt nervous before writing a test, or may have experienced ‘butterflies’ in your stomach before a big game, first date, or job interview. Maybe that small feeling of anxiety even gave you a bit of a thrill, sharpened your senses, or helped you to have a competitive edge.

While anxiety is useful a times, if it becomes persistent or the norm rather than the exception, or if our efforts to avoid it conflict with living our best lives, then we must recognize it as a disorder. Anxiety as a disorder is a significant social problem. People with anxiety often find it difficult to lead full lives; they may not be able to deal with common social interactions. They are in emotional pain and find it hard to focus. There are also financial repercussions to anxiety, like physical illness and having to miss work. In any case, people suffer inside, sometimes terribly.

In other words, anxiety is based on the adaptive strategies of fear, thinking about the future, staying vigilant in situations that may require action. But when it becomes a disabling general state of mind or keeps us from living our lives to their full potential, it becomes a disorder, and something we should work on to in order to improve our quality of life.

Those who study human mental and emotional states from a scientific point of view have come up with various theories of how to partly “cure” or healthily manage anxiety disorders, and the theories they have about why anxiety becomes a problem for some of us help explain the solutions they propose. We’ll take a closer look at the four most prominent approaches that have emerged in the last 120 years or so.

Sigmund Freud: Anxiety as Neurosis

Sigmund Freud: Anxiety as Neurosis

The term anxiety was rarely used by doctors and scientists until the twentieth century. Prior to the groundbreaking work of Sigmund Freud (1856-1939), mental illnesses were generally assumed to be caused by nerve damage or lesions on the brain (earlier still, people believed that the sufferers were possessed by evil spirits, that they were weak-minded, or otherwise to blame for their illness).

Freud’s discovery was that physical symptoms, including the emotional disruption caused by anxiety, could be brought on by imaginings, unconscious images, submerged memories, inner conflicts, and other half-conscious and distorted thoughts. This revolutionized the way society viewed mental illness in general.

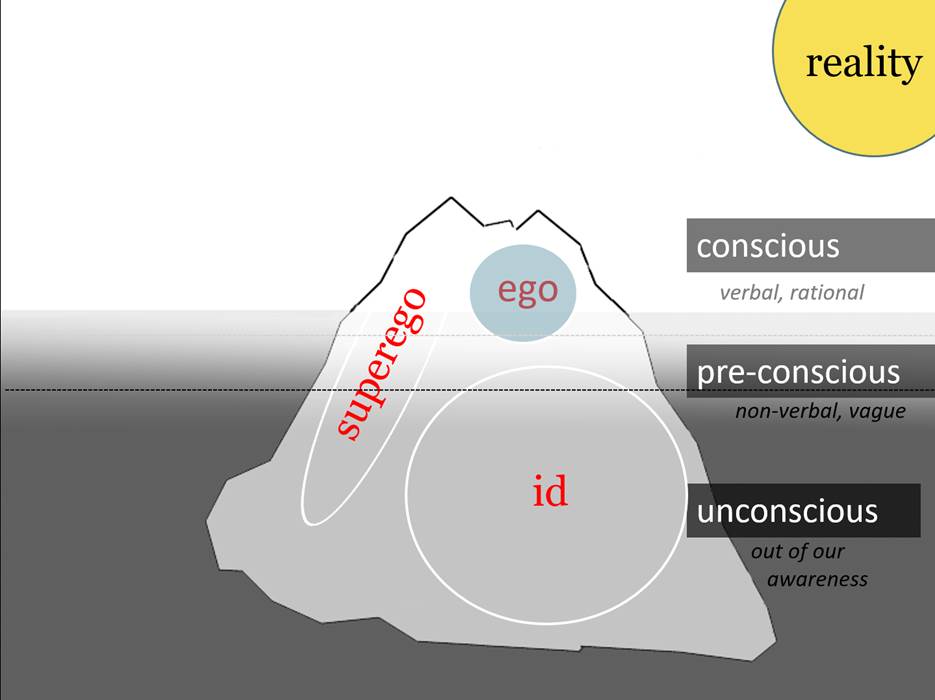

Freud characterized the human mind as made up of three parts: the id, ego and superego.

The id is our infantile and animal self; it’s mostly unconscious (we can’t directly access it or translate it into conscious thought and language). It just wants or doesn’t want. Like a baby it desires in an unreflective way, hates freely, has no conscience. It is all primal feelings: hunger, fear, desire, need, anger, aggression, etc.

The ego is the conscious, rational part of our psyche. If we listen we can hear it thinking; it probably does a lot of its thinking in language. It’s the part of you that is understanding this as you read (assuming you are understanding and reading!). It is the part of your inner self that is coherent (or at least the most coherent) and it is the only part of ourselves we can be fairly fully aware of. When you say “I …” it is the ego talking. (“Ego” is actually the Latin word for “I” – Freud’s translators chose it to show that it is a technical concept, but in the original German Freud simply spoke of the “Ich” – German for “I”) The ego is the part of us that deals with the outside world, and also the part that tries to manage the other two parts of our psyche.

The superego is the last part of the self to develop. It is a partly conscious and partly unconscious dimension of us, and in Freud’s view it is formed from the influence of our early caregivers, and then later of our teachers, friends, heroes, culture, and society in general. The superego is the part of the mind that tells us how we should be. It tells us what is right and wrong and it holds our ideals for ourselves in it.

Although it is our moral center, we should not assume that the superego’s morality is correct or realistic. Like the id, it is not entirely conscious and it is not always open to rational thought or being questioned. So it should not be said (as sometimes it is) that the id is “the devil on our one shoulder” and the superego is “the angel on the other shoulder.” It would be better to think of the id as the baby on our one shoulder and the superego as the parent/hero/ideal on the other shoulder.

Your superego may have been shaped in ways that aren’t particularly good or right. For instance, your superego could think that self-promotion is the most important thing in the world, and that you are permitted to do anything to achieve your goals. Your ideals and your "morals," right or wrong, good or bad, reside in your superego.

As an example, think of having a craving for some cake. In your psyche, your id may be shouting from the subconscious: “Caaaaake!! I want to eat a whole cake!!!” Your superego, meanwhile, might be muttering something like “You’re disgusting! You’re already too fat. You should be thinking about exercising, not about cake!” Your ego has to deal with these two often extreme and not very realistic parts of you, and try to use rationality (analysis, logic, etc: thought) to somehow resolve the conflicts between your desires and your ideals. Maybe it says something like “Hey, here’s what we’ll do. We’ll go to the store and we’ll buy a slice of cake. We’ll eat half of it tonight, and save the other half until tomorrow. And maybe we can go for a jog tomorrow.”

Then you go to the store and they are all out of cake. That’s reality. The ego has to deal with the demands of the id and the superego and with reality, all at the same time!

Freudians sometimes picture the self as an iceberg, to draw attention to how much of our inner psyche is actually submerged (unconscious).

Freud believed the anxiety displayed by his patients was because they had failed to deal with the impulses from their ids and the conflicts those impulses had with the demands and threats from their superegos. Eventually, he concluded that anxiety was a “neurosis” — a mental dysfunction in which symptoms of uneasiness, irritability, pessimism, panic attacks, nausea, and phobias were produced by unresolved conflicts in a person’s mind, by conflicting, and usually “repressed” aspects of one’s thoughts and emotions that led to physical symptoms.

Freud demonstrated how sometimes conflicts we cannot resolve or traumas and fears that are too painful get “repressed,” pushed down into the unconscious. Some of us have repressed a lot of such conflicts and traumas when we were young and powerless, but the repressed impulses, fears, and childish fantasies, and the unresolved conflicts and turmoil continue to stew in the unconscious and push themselves up into our waking lives in the forms of symptoms and “neuroses,” including anxiety.

Freud called such anxiety “neurotic” (“all in your head,” repetitive, and self-perpetuated) to distinguish it from normal anxiety, justified by real-world factors. These would include situations like your fear of being bitten by a large barking dog that is right in front of you, or falling down a steep set of icy stairs that you really should be careful on, or making the wrong decision about a life-altering situation, where you are understandably worried about what the outcome will be and can’t be sure you are making the right decision. Those are normal situations for anxiety, though if you worry about any of them to excess, it becomes neurotic, and the source of the excessive anxiety needs to be looked for in your unconscious.

If your feelings are a response to a real danger (outside your own mind and imagination and unconscious) they are not a mental health problem. If you feel anxiety about the pandemic or the American election, these are not pathological feelings but noraml, healthy ones. Again, Freud contrasted this with neurotic anxiety—where the ego feels overwhelmed by the demands of the id and the superego (for instance, you worry you will do something that might result in socially unacceptable behaviour, like violent road rage or hitting a stranger on the street). Realistic anxiety “arises from threats in the external environment; neurotic anxiety from within, though we are unaware of its true cause. Realistic Anxiety helps us; neurotic anxiety can make our life a misery.”

If your feelings are a response to a real danger (outside your own mind and imagination and unconscious) they are not a mental health problem. If you feel anxiety about the pandemic or the American election, these are not pathological feelings but noraml, healthy ones. Again, Freud contrasted this with neurotic anxiety—where the ego feels overwhelmed by the demands of the id and the superego (for instance, you worry you will do something that might result in socially unacceptable behaviour, like violent road rage or hitting a stranger on the street). Realistic anxiety “arises from threats in the external environment; neurotic anxiety from within, though we are unaware of its true cause. Realistic Anxiety helps us; neurotic anxiety can make our life a misery.”

Freud’s method of treating neurosis was psychoanalysis, or the “talking cure,” where patients talked to an analyst as freely as possible about their dreams and childhoods, their fears, desires and anxieties and imaginings in order to reveal clues about their subconscious, and bring that repressed material into conscious thought, where it could be more realistically assessed and rationally managed.

Looking into the unconscious and all the unarticulated feelings and imaginings there, and exploring the early childhood origins of the stuff that goes on in your mind can help you understand your anxiety and deal with it in a more adult, less reactive and helpless-feeling way. I personally see a therapist, and part of what we do is discuss what my childhood was like, patterns from my interaction with family and other important figures in my early life, and clues to what is secretly bothering me that can be found in dreams and other irrational, seemingly meaningless aspects of my experience.

Behaviourism

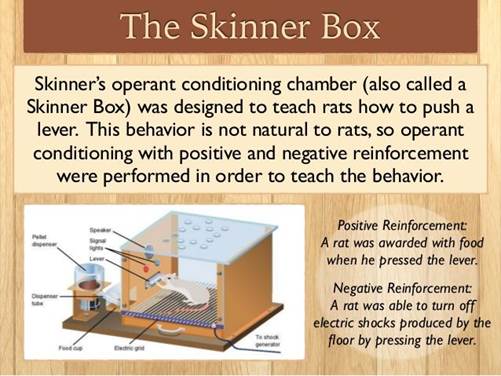

Behaviourism aims to be a scientific approach, with a focus on what can be observed.

Behaviourists mostly rejected Freud’s idea that there is a conflicted self with an ego, superego, and id, and a massive unconscious self that can only be explored indirectly. They argued that Freud’s views were not scientific – you can’t see or measure the superego, for instance; it's just a convenient idea. For a Behaviourist, Freud’s three parts of the psyche are entirely speculative and poetic notions, quite possibly the products of Freud’s own imagination. Thoughts, emotions, dreams—all were considered by the Behaviourists to be irrelevant because they cannot be studied scientifically.

As Behaviourists see it, all your actions, emotions and behaviours are the product of your combined environmental influences and experience, which have conditioned you. If you are anxious in some situations, you have been conditioned to be anxious, by repeated experiences in your upbringing, and your throughout your life as a whole. All behaviour is “learnt” by interacting with our environment, including other people. Behaviourists would agree that our early caregivers are among the most profound influences on our "conditioning," but they would reject as unprovable the idea that we are all full of unconscious conflicts and parts of ourselves that we need to bring out into consciousness. For Behaviourists, we are more like simple mechanisms. We can be trained to behave in particular ways, like lab rats; and in some cases our experiences have conditioned us to be anxious in certain circumstances. If we have been “trained” (probably not intentionally, but simply by repeated experiences) to associate anxiety with a thing or situation, we can also be untrained, through further conditioning

.

Conditioning may be intentional, as when a parent punishes you for a behaviour they don’t want you to display and rewards you when you behave in a way they like, but overall it is less explicit than that. If a parent tells you that you won’t get your allowance if you don’t act more polite, that isn’t conditioning. That’s a rational “deal” they’re making with you. Conditioning happens unconsciously over a long period in which feelings are repeatedly associated with certain sets of circumstances and/or certain behaviours. We learn to behave in certain ways, because our experience has given us positive reinforcement for behaving in those ways. We learn to be anxious in certain circumstances because we have previously been anxious in similar situations and perhaps that was reinforced by caregivers or other aspects of our experience.

Conditioning may be intentional, as when a parent punishes you for a behaviour they don’t want you to display and rewards you when you behave in a way they like, but overall it is less explicit than that. If a parent tells you that you won’t get your allowance if you don’t act more polite, that isn’t conditioning. That’s a rational “deal” they’re making with you. Conditioning happens unconsciously over a long period in which feelings are repeatedly associated with certain sets of circumstances and/or certain behaviours. We learn to behave in certain ways, because our experience has given us positive reinforcement for behaving in those ways. We learn to be anxious in certain circumstances because we have previously been anxious in similar situations and perhaps that was reinforced by caregivers or other aspects of our experience.

Your parents, for instance, may condition you without knowing that they are doing it. Suppose a baby shouts “Let’s eat!” just like its father does and everyone at the dinner table laughs at this adult-sounding and hearty phrase, and mother rushes over and gives the baby a kiss. Tomorrow night, the baby does it again, and everyone laughs and mom thinks it’s adorable again and the baby gets more attention. Eventually, the baby may be conditioned because it is repeatedly “rewarded” for these antics. We have the beginnings of a career comedian or impressionist here. This isn’t a conscious decision or an explicit agreement that has been made with the baby by the adults, and it’s not intentional training on the part of the parents, but it ends up reinforcing the baby’s tendency to act like that, and is thus “conditioning” the baby by reinforcing its behaviour.

Similarly, we learn anxious behaviour through this kind of conditioning. If you have a lisp and your classmates giggle every time you speak in class, you will likely come to feel anxiety about speaking and perhaps about going to school at all. Your classmates aren’t trying to train you to be afraid to speak, but their involuntary laughter does condition you to be averse to it.

Behaviourists focus on the fact that humans are animals, and like other animals they can be "trained" using positive and negative reinforcement. An anxiety disorder can be seen as a result of our conditioning.

A forerunner or founder of the movement, Ivan Pavlov, conducted a classical conditioning experiment on dogs, training them to salivate at the sound of a bell. He would show the dog some meat and the dog would salivate because the meat looked yummy. Pavlov rang a bell whenever he showed the meat to the dog. The dog eventually associated the bell sound with the experience of hungering after the meat. in the end, even if Pavlov didn’t present any meat along with the bell, if the dog heard the bell it would start salivating. It had come to associate (not consciously, but more in its nervous system) the physical experience of hunger for meat with the sound of the bell and would respond physically as though the meat were there, even though there was only the inedible, otherwise unappetizing sound of the bell. This is conditioning. A stimulus is associated with a response so many times that the animal is “trained” to have the response when the signal is present. Anxiety is a physical experience like having one’s mouth water. Through conditioning we are probably not consciously aware of, we have somehow come to associate certain things or situations with the feeling of anxiety, even if realistically they shouldn’t cause us fear.

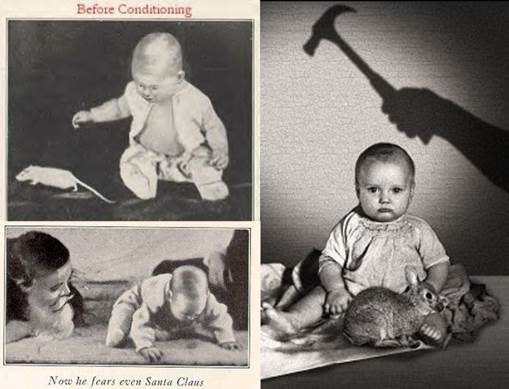

In 1920 the behaviourist psychologist John B. Watson and the grad student Rosalie Raynor, researchers at Johns Hopikins University, showed that humans can be conditioned just like other animals. In an experiment that would be considered unethical today, they were able to condition a learned pattern of fear (a phobia) in an infant. They presented “Little Albert” with white furry objects, and he acted like the curious child he was, happily reaching out to touch them. Most humans are not naturally afraid of rats; we learn that fear. They presented Albert with a soft white rat and Albert showed interest. But then they paired this “neutral” stimulus, the rat – about which Albert had no feelings one way or the others - with a startling conditioned stimulus (a very loud noise from a gong), and the baby was frightened and cried. They repeated this and eventually Albert’s fear was generalized to other small furry white things. When they showed him Santa Claus he was terrified.

In 1920 the behaviourist psychologist John B. Watson and the grad student Rosalie Raynor, researchers at Johns Hopikins University, showed that humans can be conditioned just like other animals. In an experiment that would be considered unethical today, they were able to condition a learned pattern of fear (a phobia) in an infant. They presented “Little Albert” with white furry objects, and he acted like the curious child he was, happily reaching out to touch them. Most humans are not naturally afraid of rats; we learn that fear. They presented Albert with a soft white rat and Albert showed interest. But then they paired this “neutral” stimulus, the rat – about which Albert had no feelings one way or the others - with a startling conditioned stimulus (a very loud noise from a gong), and the baby was frightened and cried. They repeated this and eventually Albert’s fear was generalized to other small furry white things. When they showed him Santa Claus he was terrified.

Sadly Albert passed away from an illness at the age of six so it is unknown whether or not this conditioning would have had long-term effects. Watson and Rayner used the example of Little Albert as evidence for their theory that all fears were the result of conditioning: we learn them, largely by association, usually in our childhood.

Freudian theory dealt more with generalized feelings of anxiety that a person doesn’t know the cause of (because the causes are hidden in their unconscious, according to the theory). The Behaviourist approach may have insights to offer in cases of social and situational anxiety, for instance fear of public speaking, or of going out in public in general, fear of flying, and other phobias. The assumption is that our phobias and anxiety attacks are learned behaviours that have been reinforced in us. The person with the lisp who gets unwanted attention in class is a clear, though not very subtle example. They may come to fear speaking in public; a Behaviourist would say this is because of the conditioning they have experienced. Again, the conditioning isn’t necessary intentional; usually it is just something they have learned, or overlearned, through repeated exposure to situations that have caused them discomfort. People with these kinds of anxiety disorders often become avoidant, and this can prevent them from leading full lives.

O.H. Mowrer explained how irrational anxieties take root through his theory of “two-stage” anxiety. Think of someone who is afraid of flying. Maybe they refuse even to get on a plane. Due to this fear, the anxious flyer never travels by air, and this avoidance deprives them of the chance to discover how their fears are exaggerated or unjustified—“by avoiding such situations, our anxiety merely tightens its grip.” It is also clear that we do not actually have to experience an event ourselves to become afraid of its repetition. We can learn to fear from how others behave and from what they tell us. If your mother is anxious whenever the wind is blowing outside, you may gradually “catch” her anxiety about windy weather.

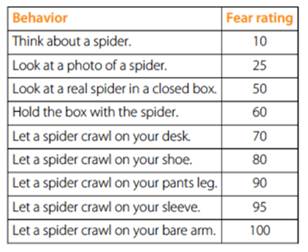

A combination of Cognitive Therapy (the next theory to be looked at) with gradual exposure conditioning can have good results in improving the lives of people with phobias and avoidant behaviours that are impoverishing their lives. The idea of exposure therapy is to re- or de-condition unwanted responses through gradual exposure to the feared thing and to slowly practice letting the anxiety exist while becoming more aware of the unreality of the threat posed, thus little by little becoming less alarmed during exposure.

The process requires courage and patience. It took years to develop an anxiety phobia, so it will take time and work to overcome it.

Perhaps even more than in the cases of other types of anxiety, phobias are often recognized by those who suffer from them as neurotic – that is, imaginary and unnecessary sources of suffering. The rational adult may understand on some level that their phobia is unreasonable, and will thus be willing to work on reconditioning themselves.

You may find it interesting to watch this brief video clip that follows the progress of a woman who has developed an unnatural fear of (wait for it!) - feathers. Presumably this was conditioned by a trauma or repeated negative association during her earlier life. It is strongly embedded in her. But she can make progress to overcome the irrational fear using her intelligence and courage and an approach that involves gradual exposure to the source of her phobia.

A similar approach is taken with people who have a fear of public speaking, for example. They might start by speaking privately and imagining an audience, then experiment with a small amount of speaking in front of trusted friends or family, then move on to saying a few words in class, despite their feelings of anxiety and aversion. It may at times be very uncomfortable. And yet gradually people can often learn to overcome or at least tame their anxiety phobias in this way.

Cognitive Therapy

The woman with the fear of feathers is combatting her phobia with a combination of gradual exposure/re-conditioning and Cognitive Therapy. The Cognitive approach to therapy combines the power of your thinking mind with your ability to make behavioural changes. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy or CBT begins with the assumption that your anxiety arises from the thoughts you are having, some of which may be barely conscious. These thoughts are often unrealistic and exaggerated and you are frightening yourself with them. In order to reduce your anxiety level, you need to use the power of your mind against this bad habit it has of terrorizing you. You need to pause when you are feeling panicked about something “real” and analyze it to see how realistic your fear actually is, and to break the habit of terrorizing yourself with your own thoughts. This takes practice; you need to work at it regularly, even if you don’t believe it will help. It will.

Those of us who are given to negative self-talk often indulge it and add to our anxiety. We become afraid of the anxiety itself; we start to worry that we will lose our minds, and so forth. This shows just how powerful our minds are, because they are coming up with these fantasies and the fantasies are truly rocking our physical/emotional sense of well-being. But our thoughts are only thoughts. It helps to recognize that and to examine the thoughts to see if they are reasonable or not. Cognitive therapy is very consistent with one of the mottos of this course: stop just feeling and imagining and instead slow down and think it through, logically and as cooly as possible.

Those of us who are given to negative self-talk often indulge it and add to our anxiety. We become afraid of the anxiety itself; we start to worry that we will lose our minds, and so forth. This shows just how powerful our minds are, because they are coming up with these fantasies and the fantasies are truly rocking our physical/emotional sense of well-being. But our thoughts are only thoughts. It helps to recognize that and to examine the thoughts to see if they are reasonable or not. Cognitive therapy is very consistent with one of the mottos of this course: stop just feeling and imagining and instead slow down and think it through, logically and as cooly as possible.

CBT focuses on teaching us to appraise threats and situations more realistically, and also to evaluate our thinking process to see how rational and realistic it really is. Anxious people have melodramatic minds. We tend to blow things up. We “disasterize” too often. My girlfriend left me; I’m unlovable; it’s because of my anxiety. My anxiety will get worse. I’ll never get another partner. Without a partner, the anxiety will grow stronger. I’ll go completely insane! (This isn’t so far from some of the semi-conscious runaway anxious thoughts I’ve had in the past! ,-) People with a tendency to anxiety,are inclined to think in extremes: I’m the most amazing person who ever lived! – I’m a complete loser! In other words, we have overactive, melodramatic imaginations, and when those imaginations go in a bad direction, they terrorize us. We panic.

In CBT, a person learns to slow down their rampaging mind and look carefully at their own thoughts from a more objective perspective. How realistic are these thoughts and fears? What evidence is there for them? How conclusive is that evidence? Is our negative interpretation really the only or the most likely one possible?

An exercise might involve us writing down how anxious we feel and a list of what is making us so apprehensive. Then we might look at each thing one by one and assess it a little more cautiously, as if from outside. This less engulfed and panicked attitude is part of the mindfulness approach as well (see below).

At the root of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy is the insight that unhelpful thoughts, feelings and behaviour are not something we are born with, but something we “learned” to do, and so they can be unlearned. An anxious person has learned, through conditioning or example or trauma, to frighten themself with negative thoughts. They can learn to use their thoughts differently, for a more positive experience and outcome. With the help of therapists, education, a bit of courage, and a lot of dedication to getting one’s mind into better shape for looking after oneself instead of disabling oneself, people can learn to take more control of their thoughts, and learn new ways to think about the things that are making them feel insecure and frightened.

Again, the cognitive approach assumes that an anxious person learned to feel insecure and apprehensive, somewhere along the way, and got good at it; with therapy, they can unlearn those tendencies, sometimes to an impressive extent!

Neurobiological Theories of Anxiety

Freud proposed a theory of anxiety that focused on the inner mind of an individual — the conflicts and repressed fantasies. The Behaviourists believed that anxiety was a “learned” response, based on conditioning by environmental stimuli. The Cognitive approach suggests that we can re-train our thinking through conscious exercise and reflection. All of these theories of anxiety fall under the heading of “nurture” — the assumption is that problems with anxiety are something that develop during childhood and adolescence on the whole, through someone’s experiences.

Now let’s look at more “nature”-oriented attempts to understand and deal with anxiety. The structure and chemical patterns of a particular person’s brain may be such that they are more susceptible to anxiety than the average person. Frequently people who suffer from anxiety do have neurological inclinations that make them more susceptible to the learned patterns of anxious thinking and feeling. If you have some tendency because of brain structure or chemistry to feel fear or panic more quickly or deeply, it will obviously reinforce any tendency your environment has encouraged in you to learn to be anxious.

Anxiety is a disorder that runs in my family. It is hard to know if so many of us are anxious because of our biology or because we are “teaching” each other to be anxious and reinforcing anxiety behaviours in one another. Maybe - most likely - it is both.

My father killed himself when I was two years old. This trauma – which I don’t remember – clearly had an impact on me and the rest of my family. Their decision to hide the fact that he had committed suicide and not talk about him too much played into the Freudian model of repression and unconscious sources of anxiety. We were no doubt all suffering from Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, but they didn’t have that concept back in those days and we all just kept quiet and tried to hide the trauma from ourselves, pretend nothing was wrong. That kind of repression creates anxiety.

It’s possible that my father had a biological predisposition to anxiety because of his brain structure and chemistry, and that I may have inherited some of that through genetics. My grandmother on my mother's side was also a nervous wreck and my mother still is. They “taught” me through their behaviour that it is natural to be apprehensive and worrying in life, and they were full of negative and melodramatic thinking and talk. Growing up in this environment would have only made me more inclined to become an anxious person if I already had neurological characteristics that would make me prone to overactive panic and fear anyway.

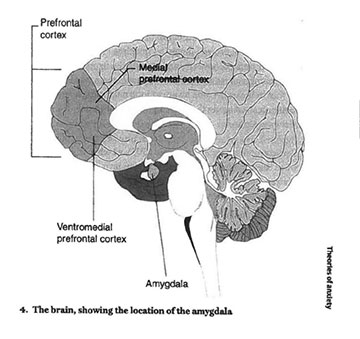

Figure from Freeman and Freeman, Theories of Anxiety, p. 31.

Brain scientist Joseph LeDoux identified the amygdala, a part of the limbic system, as the brain’s “emotional computer,” as it says in the reading. The amygdala, which is very well connected to other parts of the brain, is responsible for fear reactions, and houses unconscious fear memories. This means that the amygdala may “switch on” and make us anxious without us consciously knowing why. If there were a switch we could just throw to make the amygdala shut off, we would not feel the anxiety. When a perception or thought makes us feel threatened, the amygdala “screams out in fear.” The limbic system pays attention to this change and sends stimulation up to the cortex where these sensations inform our higher-order mental structures. We become tense, our hearts race, our muscles tighten, our breath becomes shallower and more rapid. It is as though there is a physical threat present. But there generally isn’t. The inexplicable anxiety itself then becomes the threat, and the amygdala keeps charging up our system.

When stress hormones like corticotropin are released over long periods because of persistent anxiety, it can actually change how the brain functions. Short-term memory can be impaired and the hippocampus (which helps form and store memories) can shrink. Like loneliness and depression, excessive anxiety can leave physical markers on our bodies, even if their roots are psychological.

The neurological views that are emerging are not incompatible with what Freud and the Cognitive theorists suggest: our disorder can be caused by ideas and emotions and fantasies. But it is important to remember that there are physical aspects of mental illness. In the end, neurology — medication, gene therapy, micro-surgery — may be able to do more to reduce chronic anxiety than Freud’s “talking cure.” As mental health conditions go, anxiety is perhaps the most acutely physical of them. Racing heart, stomach cramps, acid reflux, irritable bowel, muscle tension, shortness of breath, dizziness — these are just some of the most common physical manifestations of anxiety. Anxiety is a very physical kind of mental disorder.

Medication can reduce anxiety in some cases. Though they are not as precise and predictable as would be ideal, doctor-prescribed pharmaceutical treatments for anxiety can definitely help reduce the intensity of many people’s discomfort. Sometimes it is necessary to try different pills before finding one that works well, or even to come up with a “cocktail” that involves more than one medication to keep your mood on a more even keel.

The current most widely-held assumption among clinical psychiatrists is that the best approach for chronic anxiety problems is to combine medication with cognitive therapy. This is consistent with my own experience. There is a physical apspect and a mental aspect. They may both be the same thing really, but the anxiety can be addressed in both of these ways simultaneously to good effect sometimes.

I have taken sertraline (Zoloft) in many different doses for 20 years now. Currently, it is a very low dose and I am considering weaning off it entirely (I was going to try that when the pandemic hit; my doctor and I decided maybe it would be best to wait). If I were in the kind of distress I was in when I started taking it again at some point, I would certainly turn to it or explore other "cocktails." In my experience, medications don’t completely eradicate your anxiety, but they can definitely cool it down to a dull roar, and this frees up some energy to work on some of the other approaches to anxiety relief.

Maybe someday implants or less invasive forms of medical treatment will be able to greatly reduce the anxiety a person suffers from by tweaking the physical structure and chemistry of the brain directly. It would be great if the amygdala had a knob attached and you could just turn down the intensity when your anxiety is too acute.

Apart from pharmaceuticals (I mean prescription ones for the moment), various other more body-oriented therapies can help many people with anxiety. Exercise generally helps reduce anxiety. Deep breathing and practices like yoga often have dramatic effects. Promising exploration has been done on helping people recover from PTSD through theatre, improv, and other forms of creative movement!

There is a growing body of work exploring stimulating or "toning" the vagus nerve - a long nerve connecting the brain and the systems that regulate the heart, lungs, digestion, etc - so that the nervous system in effect is made to send messages back to the brain telling it that it is safe.

Interesting work is now being done on the use of psychedelic drugs like psilocybin to help those with depression and chronic anxiety. Though this could be considered a physical, pharmacological approach, one of the reasons people think it might help is because so much of the causes our our feelings are in ideas we have about ourselves and the world. Psychedelics allow you to see the world in a different patterned or relatively unstructured way, without so much judgment. Part of the reason they may be helpful is their ability to disrupt or throw into perspective ways of thinking and seeing things that have long been fossilizing in us. We see the world afresh, with less judgment, and more pleasure, or childlike interest and appreciation. Some people may experience these kinds of perspective-shifts even with very mild hallucinogens, like cannabis.

Mindfulness

It has taken me a long time to recognize the power of my own mind, and that I could turn it "from the Dark Side” to work for my emotional well-being instead of against it. Another approach I have found helpful in the case of my own anxiety is meditation and mindfulness.

Mindfulness means being present in the moment, and focusing on what is really going on right now, in reality. Most anxiety is about something this is not happening right now, and much of it is about stuff that will quite probably never happen, at least not in exactly the way we are imagining it. Mindfulness is about coming back into the present and focusing the mind on NOW and REALITY as it actually is.

Mindfulness means being present in the moment, and focusing on what is really going on right now, in reality. Most anxiety is about something this is not happening right now, and much of it is about stuff that will quite probably never happen, at least not in exactly the way we are imagining it. Mindfulness is about coming back into the present and focusing the mind on NOW and REALITY as it actually is.

It’s becoming harder and harder to live in the real present moment. Most of us are on our phones most of the time, in virtual reality, often thinking about unreal fictions in the media, or sensational far-off news happenings that are only part of our present reality because we have telecommunications. When people go to work or come to class, they may almost automatically check out from the unpleasant or “boring” present reality and go into fantasies, escapism, or – if they are inclined to think about their own lives – daydreams, future worries, past traumas, plans, repetitive analysis of past situations, idle speculation, etc.

Focusing back on what is actually happening right in front of you, or inside you, in the here and now in one’s real surroundings can be surprisingly relaxing and powerful. BE HERE NOW.

Mindfulness is related to the Cognitive approach in that becoming mindful of your anxiety itself involves letting it be (instead of trying to fix it or escape from it in a panic). The idea is to get "outside" or "above" one’s anxiety a bit and for a time: just get to know it or experience it without judgment. Understand it; care for it. But don’t just be consumed by it. There it is, my anxiety; it’s real; it’s part of me. How does it look? Watch it grow and ebb. Let the anxiety be. Contemplate it, rather than going into it or trying to get away from it. Some therapists are interested in an approach sometimes called "Willingness," in which you learn actually to "want" your anxiety, welcome it as new information from your body and soul, and recognize that you can tolerate the negative feelings without doing anything about them. Show curiosity about them instead. Your anxiety is your body wanting you to pay attention to it or to something that makes it feel threatened. If you pay that attention, the anxiety will sometimes subside.

We tend to be afraid of anxiety, and this just adds to the anxiety. Worrying about your anxiety won’t do a thing to reduce it; it will probably make it grow. Notice that. If you’re making yourself anxious, notice that. You don’t need to do anything about it, or judge yourself. You're just perceiving what's really going on, trying to avoid judgment, if anything feeling sympathy for yourself and the anxiety, which is ultimately only intended to help you survive. It's just turned up to high. Treat your anxiety with curiosity and perhaps a bit of detachment; if possible, treat it with compassion and understanding. Anxiety is a frightened child or animal; a mature, calm, positive parenting attitude toward it is useful, if you can cultivate that.

Solo meditation and deep breathing can definitely help reduce anxiety – both in the moment, and – with regular practice – more long-term. Sit or lie in a comfortable position and just pay attention to your breathing. You don’t need to change it; it’s taking care of itself. “As long as you’re breathing,” as the noted proponent of mediation Jon Kabat-Zinn likes to say, “there is more right with you than wrong with you.” Some people focus on breathing and a mantra (a word you say which takes the place of meaningful thought and logic. "Ah hahm." Just keep focusing on that word and your breathing. When thoughts come, just notice they have come, let the come and then drift by. Don't get caught up in them, but don't try to fight them either. There's that scary thought again. "Ah hahm."

I’ve found guided meditations helpful. Group meditation sessions are offered by live guides, or can be found streaming on the Internet. They might take you on a trip through your body, focusing on one part of it at a time. That can be a therapeutic “escape” from an overactive mind (wiggle your big toe; why does that part of you get so little attention and your mind so much?). Focussing on your body and how different parts feel is much more of an investment in your full self than the escapism of watching a movie or getting drunk is. There are many guided meditations available online for streaming, some free. Some of them, including many by Jon Kabat-Zinn, are specifically designed for helping people through things like anxiety and depression, trauma, dealing with chronic health issues, terminal illness, losses, and so forth. I’ve found meditation helpful in making me a less panicked, calmer and a more "together" person.

Keeping journals and writing down your anxious thoughts and feelings is another way of paying attention to and gaining understanding of your anxiety - and yourself. It is also a way of "downloading" the thinking from your head to the page and can calm some of the thinking in your head. You know the thoughts will not be lost and you have expressed them, almost as if to another person. Importantly, you have expressed them to yourself. You never have to look at your journals again, you can burn them, or you can keep them in case you want to review states of mind you have been in. I write "pages" regularly as a way of offloading worries, looking at the realism of my thoughts (or lack of realism), and getting to know myself, painful and shameful though the experience may be at times.

In summary, then, although the major approaches to anxiety I’ve told you about have different focuses, different emphases on where anxiety comes from, and different techniques to propose, I’ve personally found something to take from each of them.

I’ve seen a few different professionals over the years: psychiatrists, psychologists, psychotherapists. I’ve attended organized meditation sessions. I haven’t done yoga, but I know it would be good for me. I don't want to do it by myself, or over Zoom, but I think maybe if this pandemic is ever truly over ...

If you or someone you know is suffering from serious and prolonged anxiety, I strongly recommend getting professional help. I resisted that for years and wasted precious time that I won't get back. Thinking "I can do it myself" or "I don't want admit I have a problem" or "I will be just try to be stronger" (my mother's favourite) comes from "ego" in the non-Freudian sense, and gradiose expectations from oneself that one shouldn't look to other people for help and that asking for help is admitting there is something wrong with you. It's all right if there's "something wrong" - this is part of the human condition that most of us experience at least at times. A good therapist can guide you and help you and make it possible for you to work on yourself in a way that is unlikely if you try to do it all by yourself.

It can definitely take time to find the right match – the therapist that does you the most good. And it take time for the relationship with that therapist to develop to the point of trust and knowledge where you can start to grow and move away from your self-torturing and self-defeating habits. A great therapist might be a rare find. But even the worst therapist I have had was still somewhat helpful, and seeing them gave me space to work on myself and my problems and continue learning how to “care for my anxiety” instead of running away from it and letting it run away with my life.

For TESTING

- The Psychoanalytical (or Freudian) approach (theory of causes and methods of treatment)

- Id, Ego, and Superego; Repression and the Return of the Repressed

- The Behaviourist approach (theory of causes and methods of treatment)

- Gradual exposure re-conditioning

- The Cognitive approach (theory of causes and methods of treatment)

- The Neurological approach (theory of causes and methods of treatment)

You might find it useful to download this study sheet and fill it in as you read to faciliate remembering these ideas accurately for testing.